Economic insights provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Key takeaways:

- The Bank of Canada has cut its policy rate by 75bp so far. A stagnating labour market and economy are pointing to rising slack in the economy and are supporting the need for a further reduction in the policy rate, especially as the central bank turns its focus away from inflation risks towards downside risks to growth.

- Moreover, Governor Macklem’s recent comments suggest that: 1) the door is open to a 50bp cut, and 2) the BoC is considering accelerating the return of the policy rate towards its neutral level. Many factors support a faster reduction in interest rates.

- The sharp increase in population may be hiding a recession. As we have shown (see It’s a “Me-cession”, not a recession), if it were not for the increase in population pushing aggregate consumer spending higher, economic activity would have contracted in the second half of 2023. Hence, the Canadian economy would have been in a recession.

- This is mainly because, while consumers are reducing their individual spending or spending per capita, a continued increase in the number of consumers thanks to strong population growth means that we are consuming more in aggregate, thereby supporting overall economic activity.

- Moreover, the decline in consumer spending per capita in the current cycle so far is consistent with previous recessionary episodes, albeit less severe than during the 1980s and 1990s; this is likely due to the resilience of the labour market or lack of widespread job losses.

- As such, the resilience of the labour market can also be linked to strong population growth. With aggregate demand continuing to increase because of population growth, most businesses have not seen a decline in overall activity. Hence, they still require the same number of workers as before, thus preventing layoffs.

- As the labour market is stagnating, with job creation much lower than labour force growth, this has led to a rise in unemployment, especially for the younger cohort. This points to a rise in the amount of slack in the economy and a situation that is expected to last given weak hiring intentions.

- Preventing a worsening of the labour market is crucial to the outlook and to ensure the Canadian economy experiences a “soft landing” rather than a “hard landing”. As we have shown in the past (see It’s a “Me-cession”, not a recession and Will it be a hard landing or a soft landing? The labour market will decide), resilience in the labour market has been key to allow households and the broader economy to adapt to higher interest rates.

- Therefore, a faster normalization of the policy rate could be seen as the BoC buying some insurance against a “hard landing.

- Inflation is back to target and has between within the operational band for some months. Moreover, the breadth of inflationary pressures and recent price dynamic suggests that inflation risks are very low.

- With further interest rates cuts widely expected, a case can be made that many agents in the economy are waiting for the bottom interest rates before borrowing and taking advantage of lower interest rates, hence delaying the positive impact of lower rates. By accelerating the pace of rate cuts, the BoC could bring forward a recovery.

- Higher interest rates were not all negative for the economy: it has also led to some desperately needed household deleveraging, a major source of vulnerability for the Canadian economy.

- This deleveraging is crucial to the rebalancing of the Canadian economy. As shown in “Canada’s housing obsession is cannibalizing productivity”, constant borrowing from households over the past three decades has crowded out the business sector and explains, in part, the underperformance in investment in machinery, equipment and intellectual property.

- With this in mind, the BoC should be concerned of excessively cutting rates and facilitating a return to the unsustainable growth model of the past decade that was based on ever growing household borrowing at the expense of productive investment. It will imply some short-term pain on the household side for long term gains in the broader economy.

- Taking these factors into consideration, we expect the BoC to cut its policy rate by 50bp at the October meeting. We also believe there is a 50/50 chance of another 50bp cut in December; in our view, such a move would be warranted to accelerate the return to a more neutral policy rate. This would be followed by a 25bp cut in January, bringing the policy rate to 3.00% in early 2025, before taking a pause.

- There is a lot of uncertainty regarding where the terminal rate of the easing cycle will be. Nevertheless, it is very likely that the terminal rate will be higher than pre-pandemic level.

The Bank of Canada has lowered its policy rate by 75bp since June 2024, from 5.00% to 4.25%. However, a stagnating labour market and economy are pointing to further increases in the amount of slack in the economy; if left unchecked, this could push inflation below the target range. The BoC rotated its focus away from inflation to the downside risk to growth at the following July meeting. However, until recently, there were no signs suggesting that the central bank was ready to act more decisively without a negative shock or a worsening of the economic outlook.

Some would argue that the Federal Reserve cutting by 50bp in September 2024 opened the door to bigger cuts in Canada. However, Governor Macklem had already opened that door before the Fed’s decision, mentioning in an interview with the Financial Times on September 14th that “it could be appropriate to move faster [on] interest rates”. In our view, the Governor’s statement suggests two things: 1) the door is open to a 50bp and the hurdle to make a bigger cut is not as high as previously thought, and 2) the BoC may be considering bringing its policy rates towards neutral faster than initially expected.

With anemic economic activity, the unemployment rate drifting higher and inflation back to the BoC’s target, there are clear signs that monetary policy is no longer required to be restrictive. However, faster rate cuts may not imply deeper cuts. In other words, while the policy rate will return toward a more neutral level faster than expected, it does not mean that the BoC will cut well below neutral rate and push monetary policy deeply into accommodative territory.

Listed below are factors that supports a faster reduction in the policy rate:

Population growth is blurring the economic picture; potentially hiding a recession

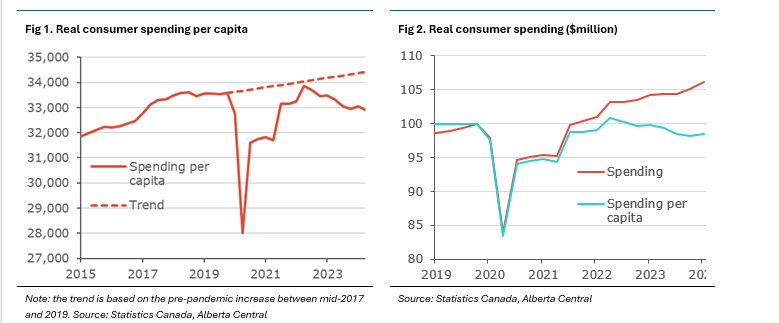

Record population growth in Canada in recent years is hiding the true extent of economic weakness. While many are focusing on the decline in GDP per capita, this is only a symptom of economic malaise. What is more indicative of the underlying weakness is the decline in consumer spending per capita. After all, consumer spending represents almost 60% of the Canadian economy.

Per capita spending has declined by about 3% since its peak in 2022Q2, roughly when the BoC started tightening monetary policy. However, aggregate spending has increased by about 3% over the same period. This means that, while individual consumers are reducing their spending, the continued increase in the number of consumers – thanks to population growth – means that we are consuming more in aggregate, thereby supporting overall economic activity.

As we have shown in “It’s a “Me-cession”, not a recession”, if it were not for the increase in population pushing aggregate consumer spending higher, economic activity would have contracted in the second half of 2023. Hence, the Canadian economy would have been in a recession.

Looking at the data since 1961 for per capita spending and GDP, we note that spending per capita decreased from its peak by 5.5% in the early 1980s recession, by 5.0% in the early 1990s, and 2.5% in the 2008-2009 recession. With a decline of 3% since early 2022, the current decline is consistent with the experience of previous recessions.

However, the decline in the current cycle remains modest so far, especially when compared to the 1980s and 1990s recessions. This is most likely due to the resilience in the labour market, characterized by a continued increase in employment, albeit slow, and a lack of widespread job losses.

We believe the fact that the labour market is holding up is likely explained by the strong population growth and the continued increase in economic activity associated with it.

Normally in a recession, the decline in economic activity means that businesses are facing lower business activity. As a result, they often need to adjust their costs and employment levels, leading to a reduction in headcount. These layoffs then reduce consumer spending due to the income shock and push the unemployment rate higher, further reducing economic activity.

In the current episode, because of the strong increase in population, aggregate demand has continued to rise. As a result, economic activity has not declined. Hence, while activity has been stagnating, businesses have not had to reduce their headcounts, as demand for their products or services has not decreased and even continued to increase. This has prevented layoffs that would normally occur during a recession and negative spillovers to the rest of the economy.

Hence, population growth has, so far and in some way, insulated the economy from a recession despite individuals reducing their spending in a similar fashion to previous mild recessions.

With a stagnating labour market, cut could provide insurance against a “hard-landing”

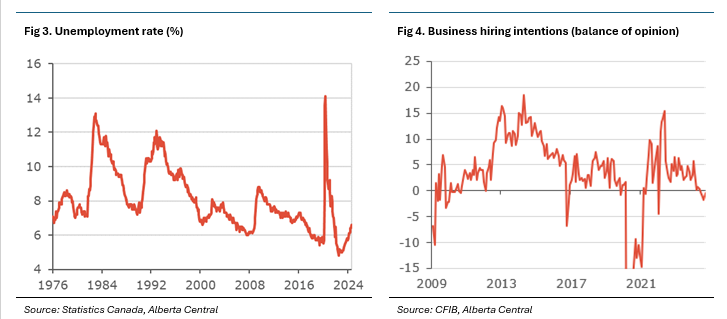

While we haven’t seen layoffs that would normally be associated with a recession, this doesn’t mean that the labour market is robust. In fact, job creation has been anemic in recent months, averaging only 22,000 over the past 6-months, about half the average increase in the labour force. As a result, the unemployment rate has gradually increased to 6.6%, its highest level since 2017, if the pandemic is excluded, but still low by historical standards.

The rise in the unemployment rate is mainly due to the economy not being strong enough to create the necessary jobs to absorb workers entering the labour force, not layoffs. As such, about only 40% of those unemployed had previously worked, close to its lowest level on record. Nevertheless, this situation is leading to the higher unemployment rate for younger cohorts, having increased to 14.5%, its highest rate since 2012. This is concerning as it has been shown that unemployment early in one’s career can have a long-term impact on their earning capacity throughout their careers.

These are signs that the amount of slack in the labour market is increasing and lowers inflationary pressures. Stronger growth will be required to prevent a worsening of the situation and, ultimately, return the labour market to equilibrium. In addition, job vacancies and hiring intentions have both weakened in recent months. While not pointing to a rise in layoffs, these indicators are hinting to continued weak job creation; consequently, further weakening would start to signal a rise in jobs losses.

Preventing a worsening of the labour market is crucial to the outlook and to ensure that the Canadian economy is experiencing a “soft landing”, rather than a “hard landing”. As we have shown in the past (see It’s a “Me-cession”, not a recession and Will it be a hard landing or a soft landing? The labour market will decide), resilience in the labour market has been key to allowing households and the broader economy to adapt to higher interest rates. More precisely, the lack of a negative shock to household income due to job losses has meant that households have been able to renew their borrowing on longer amortization periods; consequently, this reduces the increase to their monthly payments due to higher interest rates. Moreover, it also explains why, while insolvencies have increased, the increase has been concentrated in proposals (renegotiation of terms) rather than in bankruptcies.

Job losses and the associated drop in income could have a significant negative impact on the economy, especially due to the strain on heavily leveraged households. Specifically:

- It could lead to forced selling in the housing market, as households who can no longer make their payments would have to sell their homes. The influx of new listings could drastically change the housing market’s equilibrium at a time when demand is also likely to be weaker. Potential buyers will likely stay on the sideline if job security is perceived as low and prices are expected to decline. This would lead to a drop in house prices; also, the associated negative wealth effect and uncertainty would reduce household spending.

- A drop in income would likely lead to a rise in defaults and losses at financial institutions. This would lead to lenders become risk-averse to protect their balance sheets, reducing the availability of credit to households and businesses and increasing borrowing costs. The resulting credit crush would have a negative impact on business investment, consumer spending and the housing market as it would be more difficult to borrow. Consequently, a reduction in lending could reinforce the decline in the housing market, as would-be buyers would have trouble obtaining a mortgage.

As the economy slows further due to these channels, it could lead to further job losses and more financial strains on the household sector, exacerbating the downturn and potentially leading to a deeper recession.

With this risk scenario in mind, it is warranted for the BoC to return its policy rate faster towards neutral to avoid a deterioration of the labour market. In other words, by cutting rates faster, the BoC could buy some insurance against a hard landing.

Inflation is tamed and no longer a concern in the short term

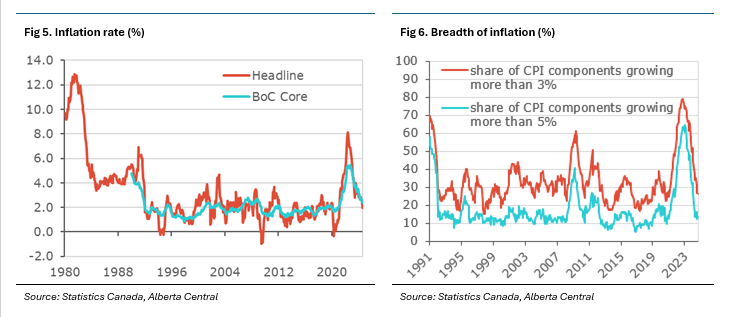

The BoC’s primary objective is to ensure price stability, as defined by its inflation targeting framework, which is to keep inflation between 1% and 3%, aiming at the 2% midpoint. This objective has been reached in recent months.

Headline inflation has returned to below 3% since January 2024 and came in directly at the 2% target in August 2024, while the BoC’s measures of core inflation have been below 3% since March and came in at 2.35% the same month. Moreover, the breadth of inflationary pressures, as measured by the share of CPI components rising by more than 3% and 5%, have also declined and is well within its historical norms. Additionally, short price dynamics, as measured by momentum in core inflation or the 3m/3m annualized change in prices, has been below 3% since the beginning of year. All these factors suggests that inflationary pressures are tame.

Inflation is expected to rise somewhat in the coming months to about 2.7% by early next year, remaining below 3%. This acceleration in inflation is mainly the result of base effects, rather than the start of concerning prices dynamic. Similarly, the BoC measures of cores inflation are expected to remain between 2.0% and 2.5% for most of next year because of a base effect.

Agents could be delaying actions for the bottom in interest rates

With interest rates widely expected to continue to decline in the coming months, a case can be made that many agents in the economy, businesses and households, are waiting for bottom interest rates before borrowing and taking advantage of lower interest rates.

For example, potential homebuyers are likely delaying coming back to the housing market for lower interest rates and an increase in affordability, albeit marginal, that will accompany lower rates. This likely delays the impact of lower rates on the sector. Similarly, some businesses could also be delaying their investment decisions for the same reason. However, we note that uncertainty regarding the economic outlook is likely a greater factor delaying business decisions.

Nevertheless, if it is the case that actions are being delayed until interest rates have bottomed, this situation means that by moving slowly on interest rates, the BoC could be delaying the positive impact of lower interest rates on the economy and, potentially, leading to a longer period of underperformance before the economy rebounds.

Conversely, this suggests that by moving faster towards a return of rates to neutral, the BoC could promote a faster recovery and reduce the downside risks to the outlook.

The necessary deleveraging is happening and needs to continue

While many observers focus solely on the negative impact of higher interest rates, it is important to take into consideration that higher interest rates also positively impact the economy. With interest rates at their highest level in more than a decade, we are finally seeing some desperately needed household deleveraging and increased household savings.

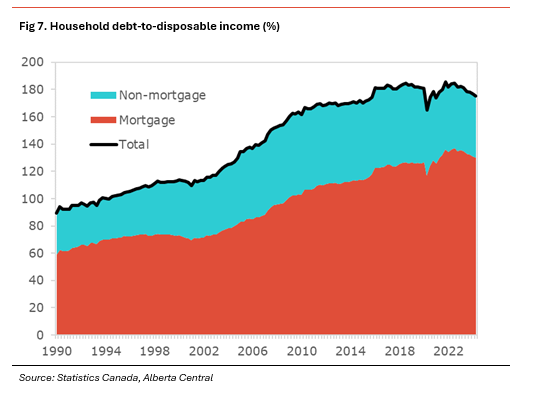

A high level of household debt, standing at more that 175% of disposable income, is a major source of vulnerability for the Canadian economy. As mentioned earlier, a high level of debt and the associated elevated debt-service ratio make households vulnerable to negative shocks, especially a decline in income. Hence, a reduction in indebtedness for Canadian households is necessary.

Since the BoC started to increase its policy rate in early 2022, the debt-to-disposable income ratio has eased slightly, from a peak of 185% in 2022Q3 to a current level of 175%. Nevertheless, it remains extremely high by historical standards and one of the highest amongst G20 countries. Similarly, the savings rate has increased to 7.2%, its highest since 1996, and much higher than the average of 3.3% from 2000 to 2019; this supports deleveraging, but at the expense of weak consumer spending.

This deleveraging is crucial to the rebalancing of the Canadian economy. As shown in “Canada’s housing obsession is cannibalizing productivity”, constant borrowing from households over the past three decades has crowded out the business sector and explains, in part, the underperformance in investment in machinery, equipment and intellectual property over the period. Hence, the debt binge of households has negatively impacted productivity in the country.

The BoC should be worried about perpetuating this situation by cutting interest rates too much and preventing the essential deleveraging of the household sector. While some are pointing that many borrowers will be forced to renew their borrowing at higher interest rates, we believe two important considerations need to be considered:

- To prevent a jump in mortgage payments, interest rates would need to drop significantly. We estimate that it would require a decline of about 350bp in the policy rate and 200bp on longer maturity, especially the 5-year segment, to prevent a jump in mortgage payments. Such a decline in rates would be consistent with a hard landing. However, in such a scenario, interest rates may not be the reason for household’s financial stress but rather income losses due to job losses, and;

- As harsh as it may sound, the question should be asked whether policymakers should bailout overleveraged households from when interest rates were at the lowest on record and more likely to climb than ease down further? The BoC should focus on avoiding a hard landing and mostly worry about the impact a rise in financial stress would have on the economy and inflation, its primary mandate.

Overall, rate cuts shouldn’t push interest rates too deeply into accommodative territory. Doing so would bring us back to the unsustainable growth model of the past three decades, where growth was perpetually supported by household borrowing and house flipping at the expense of productive investment. This will imply that we should expect consumer spending to remain lacklustre for some time and is likely to remain a source of weakness to the economy.

Outlook for the policy rate

With all these points in mind, we expect the BoC to cut its policy rate by 50bp at the October meeting. We also believe there is a 50/50 chance the BoC will cut by another 50bp cut in December; in our view, such a move would be warranted to accelerate the return to a more neutral policy rate. This would be followed by a 25bp cut in January, bringing the policy rate to 3.00% in early 2025. Subsequently, the BoC should take a long pause to better assess the impact of this rapid decline in interest rates on the economy.

There is a lot of uncertainty regarding where the terminal rate of the easing cycle will be; i.e at what level the policy rate will reach a trough. This level of interest rates will depend on the neutral rate, global economic conditions and the evolution of the Canadian economy. Nevertheless, it is very likely that the terminal rate will be higher than its pre-pandemic level.

Conclusion

The BoC will need to carefully navigate the need for lower interest rates to prevent a worsening of the labour market and potentially leading to job losses that could lead to a hard landing, with the need for rates to be high enough to ensure that the needed rebalancing of the economy and household deleveraging continues without tipping the economy into a recession.

The key theme for the economy is that short term pain (household deleveraging and subdued consumer spending) will be required to ensure long term gains and prosperity (reduced vulnerability, increase productive investment).