Economic insight provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Main takeaways

- Despite record levels of oil revenue since mid-2021, the Alberta economy is not seeing an associated boom, as a smaller share of revenues is staying in the province.

- Instead, a greater share of revenues is being returned to shareholders, most of whom are foreigners, and a smaller share is reinvested into operations in the province.

- The current weak investment in the province could explain the wage and income underperformance we have previously identified, which led to a decline in Albertans’ purchasing power over the past few years.

- Over the past two decades, there has been a clear relationship between increased investment in Alberta and faster wages and income growth in the province compared to the rest of Canada, leading to the Alberta Advantage.

- However, weak investment since 2015 has led to a constant underperformance in Alberta’s wages and income relative to the rest of the country, leading to an erosion of the Alberta Advantage.

- This pattern is not due to sectors linked to the oil industry; it is a broad-based relationship that holds across almost every industry or age cohort of the labour force.

- Strong hiring in highly-paid sectors during the boom years led to acute job shortages and fierce competition for workers across sectors. As a result, wages broadly increased faster in the province than in the rest of the country.

- With labour shortages less intense in the province since the end of the boom in 2015, wages in Alberta are now underperforming the rest of the country.

- With investment remaining weak, despite record oil revenues, it is likely that wages and income in Alberta will continue to underperform and converge to the national average.

- However, with the strong link between investment and wages and income, it could be argued that a sharp increase in investment in the province in the coming years to meet its commitments to reach net zero could help maintain – and maybe even restore – some of the Alberta Advantage.

- Such an outcome could potentially change the narrative around the costs associated with reaching net zero to the potential benefits in the form of increased prosperity.

Bottom line

In the Fall of 2022, we wrote a report bringing attention to the fact that record levels of oil revenues in Alberta were having a significantly smaller impact on the broader economy compared to previous episodes (see Where’s the boom? How the impact of oil on Alberta may have permanently weakened).

The primary reason for this shift is that, compared to previous boom cycles, a smaller share of oil revenues is now staying in the province. Specifically:

- Oil producers are returning a greater share of revenues – in the form of dividends and buybacks – to shareholders. Currently, about 13% of revenues are returned to shareholders, compared to 3% in 2014. This difference is exacerbated by the fact that, as roughly 75% of shareholders are foreigners, most of these payouts are leaving the country.

- Oil producers are currently reinvesting a smaller share of revenues into their operations; 7% of revenues are currently being reinvested, compared to 25% back in 2014. Moreover, the type of investment (i.e. focused on efficiency gains) likely has a lower economic multiplier than investment in new projects.

As a follow-up to the preceding publication, this report examines how the investment cycle over the past two decades, especially in the energy sector, has had a significant impact on the Alberta economy and how it helps to explain the rise and fall of the Alberta Advantage;, this refers to the difference in wages and income in the province relative to the rest of the country (see The Alberta Advantage is melting away).

The rise and fall of the Alberta Advantage

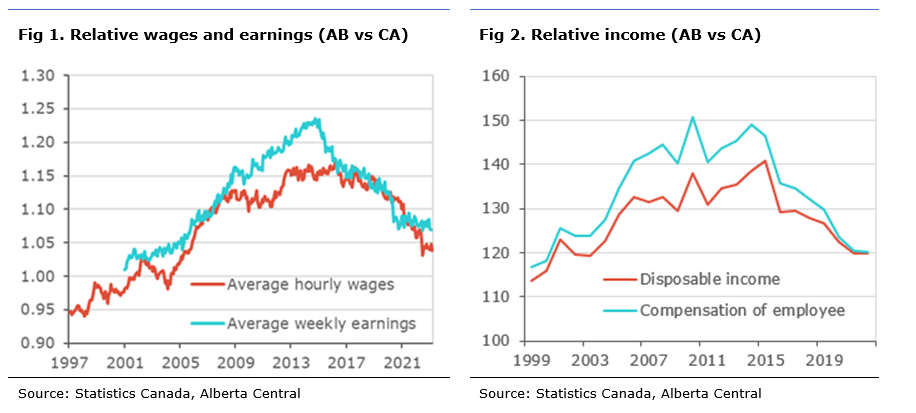

As we noted in The Alberta Advantage is melting away, Alberta’s wages and income remain higher than in the rest of the country. However, the difference between the province and the rest of the country is gradually shrinking and, according to some measures, no longer exists.

These observations were based on a number of indicators, including: average wages for permanent workers, median wage for permanent workers, average weekly earnings including overtime, compensation of employee per household, and disposable income per household.

As the aim of this report was to analyze how the purchasing power of Albertans is faring in the recent period of high inflation, the period was limited to the most recent four years (2019 to present). However, many of the trends identified in the report predate 2019; in fact, the gradual erosion of the Alberta Advantage began in 2015. Therefore, the catalyst for the province’s shrinking advantage during this period may be attributed to the economic bust and subsequent recession, as oil prices fell dramatically.

In 2015, average wages for permanent workers were approximately 16% above the national average, while average weekly earnings, including overtime, were about 23% above. Currently, these two measures are only 4% and 7%, respectively, above the national average.

Going back further, we find that, in the early 2000s, wages and income in Alberta were either almost equal to the national average or only marginally higher. Rapid wage and earnings growth began around the mid-2000s, thereby leading to higher measures relative to the rest of the country.

A similar trend is also observed with income data, the only difference being that income levels are much higher in Alberta than in the rest of the country. That year, Alberta’s disposable income per person aged 15 years and over was 34% above the rest of the country. This figure has since gradually declined to 11%, closer to its 1999 value.

In light of this information, it is critical to understand the factors that led to Alberta’s wages and income to grow at a significantly faster rate than the rest of the country in the years leading up to 2015.

The labour market composition does not matter

Many observers would point out that the wages and income outperformance in Alberta was likely the result of a rise in highly paid jobs during the oil boom of the 2000s and early 2010s. After all, between 2005 and 2014, the natural resource extraction sector gained 43,000 jobs, the construction sector added 91,000 jobs, and the professional, scientific and technical sector grew by 60,000; all of these sectors have a strong link to booming oil investment (see Where’s the boom? How the impact of oil on Alberta may have permanently weakened). Combined, these represent a little more than 40% of total job creation in the province over that period.

As a result of these sharp job gains, the share of the natural resources extraction industry of total employment rose from 6% to 8% between the early 2000s, before peaking at 8% in 2015. (It is currently slightly above 5%.) If we include the construction sector, a sector that benefits from spillovers from the oil and gas industry, the proportion of both sectors ranged from 13% in the early 2000s to 19% in 2015. Currently, these two industries account for 15% of jobs in the province.

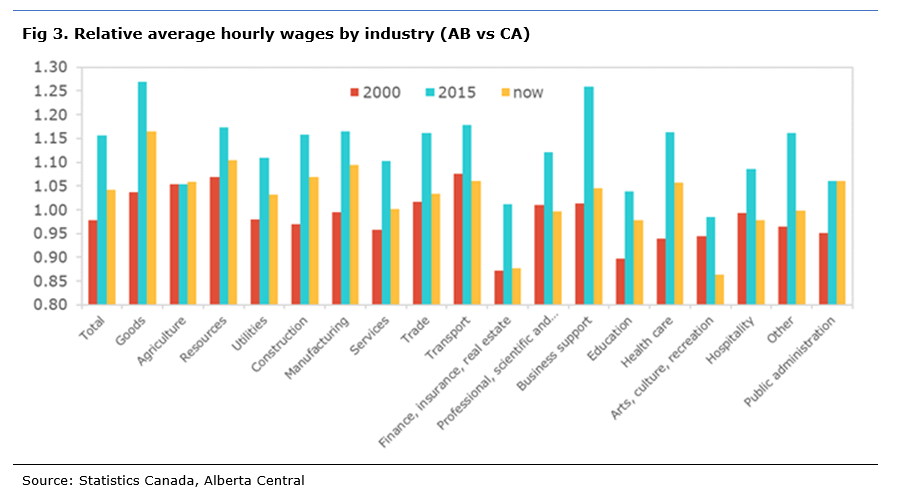

While the hypothesis that the decline in the wage advantage is due to the composition of employment is intellectually appealing, the data does not support this theory. This is because:

- If we calculated Alberta’s wage measures keeping the share of every industry constant to their 2014 levels, we find only marginal differences in relative wages relative to the rest of the country and the trend observed over the past two decades remains intact.

- If we look at the relative wages between Alberta and the rest of Canada at an industry level, we find similar trends (i.e. an outperformance in wage growth from mid-2000s to 2015 and then an underperformance since) in almost every industry. This trend is also visible in industries unrelated to the oil and gas sector, such as health care.

- Even looking at details between cohorts of the labour force, we find very similar trends by age and sex.

Hence, the factors that led to the wages and income outperformance had a broad impact on the Alberta economy.

The investment cycle, hiring boom and wage pressures

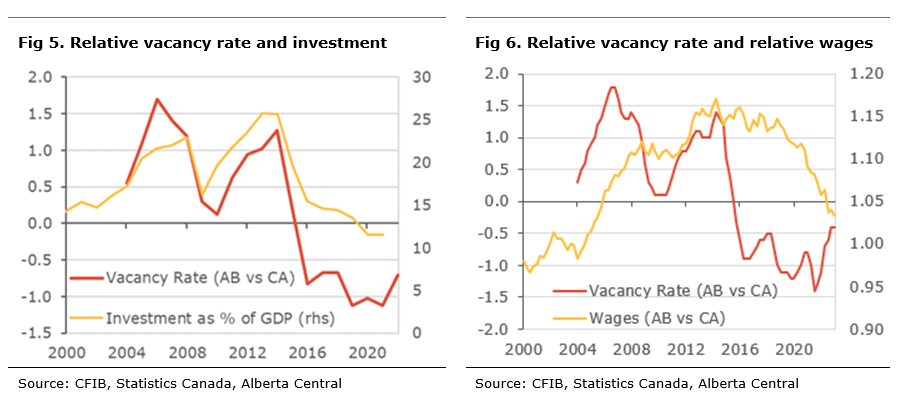

The outperformance in wages and income seems to be linked to the investment boom in Alberta between the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s.

Interestingly, there is a strong correlation between this period of wages and income outperformance and the strength of business investment in Alberta.

By using discontinued data on disposable income to complement current data, we are able to look at longer trends; starting in the 1980s, we find a very strong correlation between the share of business investment in GDP and the level of disposable income per person relative to the rest of the country. This relationship suggests that rising business investment in Alberta is linked to faster increases in wages and income.

For obvious reasons, the investment cycle in Alberta has been linked to the oil and gas industry. Relative to investment in the rest of the country, Alberta started to outperform meaningfully in the 2000s when oil prices rose above $30 a barrel, after having spent most of the 1990s close to $20 a barrel. The further increase in oil prices that began in 2004 turbocharged investment in the sector in the following years.

This period also coincided with massive investment in the oil sands sector, as the higher prices made its development economically sustainable. However, strong investment on its own does not necessarily explain why wages and income in Alberta significantly outperformed the rest of the country.

The massive investment in the oil and gas sector led to strong hiring, thereby impacting the rest of the economy. As mentioned earlier, the increased importance of investment in the oil and gas industry is responsible for more than 40% of the job gains between 2005 and 2015; this figure is limited to employment in the natural resource extraction, construction and professional, scientific and technical employment sectors.

This strong hiring in highly paid sectors led to some acute labour shortages in Alberta, leading to competition across sectors to attract workers. As a result, other sectors of the economy had to offer better wages; otherwise, they faced the risk that workers would leave for sectors offering higher wages. The result was an Alberta Advantage that extended beyond sectors directly related to strong investments in oil and gas.

We can observe the impact between the tightness in the labour market and the intensity of the labour shortages on wages. Looking at the relative level of job vacancy rates between Alberta and the rest of the country, we can see that the higher the difference in job vacancy rate, the stronger Alberta’s wage outperformance. Conversely, a lower level of job vacancy rate in Alberta relative to the rest of the country has led to weaker wage growth in the province.

However, with data only available for the investment cycle of the 2000s, it is not clear whether the labour shortage that resulted from the surge in investment would happen in another investment boom or whether specific conditions at the time led to the wage outperformance. This could be due to the fact that the investment was very much labour intensive and the hiring was concentrated in highly paid sectors.

Implication for the future and convergence to the rest of the country

The link between the Alberta Advantage and the investment cycle could have some important implications for the Alberta economy. However, with data only available for one investment cycle, it is not clear whether another investment boom would lead to the same labour shortage and outperformance in wages and income.

Nevertheless, the recent trend suggests that the current weakness of investment in the oil and gas sector, despite record levels of revenue, should be a source of concern. It means that the current underperformance in wages and income growth in Alberta is likely to continue unless oil producers decide to reinvest a greater share of their revenues into their operations.

As a result, we should expect a continued gradual erosion of the Alberta Advantage, likely to a point where wages and other income measures could reach parity with the rest of the country. This convergence is likely to be somewhat faster in the future as Alberta attracts a large number of migrants from other provinces in search of lower housing costs and better pay. This situation will keep labour supply higher in the province than in the rest of Canada, thereby putting downside pressures on wage growth. This wage convergence is precisely what economic theory would predict when wages are higher in a region and labour can move freely between areas.

Based on current trends, wages and weekly earnings are likely to be on par with the rest of the country within the next few years. Disposable income could remain above the national average in the longer term, thanks to lower taxation in the province and the continued impact of high oil revenues on other sources of income, such as investment income.

However, with Alberta’s wages and income outperformance linked to investment, it could be argued that a sharp increase in investment in the province in the coming years to meet its commitments to reach net zero could help maintain – and maybe even restore – some of the Alberta Advantage.

Such an outcome would dramatically change the discussion around the costs associated with reaching net zero to the potential benefits in the form of increased prosperity, as well as future-proofing some of our key current and future industries.

In a future report, it would be worthwhile to explore whether an investment boom in energy transition and decarbonization could drive Alberta’s next boom and renew Alberta’s Advantage.

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.