Economic insights provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Now available – download the full 2025 Economic Outlook Report here!

Key takeaways:

- With the Bank of Canada (BoC) expected to continue easing monetary policy in 2025, there is significant uncertainty regarding the extent of expected rate cuts; more specifically, the terminal rate at which central banks will stop providing further stimulus.

- A key factor determining the terminal rate in the current easing cycle will be the level of the neutral rate, as the neutral rate determines the policy stance of monetary policy. However, the neutral is unobservable, pushing Governor Macklem to say that the BoC may need “to discover” where the neutral is.

- This is also complicated by the fact that economic literature often refers to two definitions for the neutral rate: 1) the medium-to-long-run neutral rate, on which the estimate provided by the BoC is based, which is the rate of interest that should prevail after the effects of business cycle shocks have dissipated and the economy is at equilibrium, and 2) contemporaneous neutral rate, which is the rate of interest that would ensure a balanced economy or an output gap of 0 in every period.

- Although many analysts focus on the BoC’s estimate based on the medium-to-long-run definition, this overlooks the impact of shocks that could temporarily move the neutral rate. Instead, a macro framework based on a neutral rate that can vary in the short term due to shock before converging gradually to a long-term anchor is preferable.

- The balance between the demand for funds (investment) and the supply of funds (savings) determines the neutral rate. The key determinants of this equilibrium are: potential growth, government borrowing, global savings and investment balance, the propensity of households to save and financial conditions.

- The expected sharp deceleration in population growth in coming years will broadly impact the Canadian economy, including restraining aggregate consumer spending and weaknesses in some areas of the housing market.

- The main impact will be a meaningful slowdown in potential growth because of weak labour input growth, while any improvement in labour productivity is likely to be modest in light of the recent dismal performance. As a result, the neutral rate is likely to decline.

- A higher global neutral rate due to higher potential growth in the U.S. and a large U.S. government deficit will not prevent a moderation in the Canadian neutral rate.

- We believe these developments indicate that the neutral rate in Canada will likely be around or even slightly below the lower bound of the BoC’s estimate, depending on whether the government fully enforces its immigration targets. This means that monetary conditions will remain restrictive until the policy rate reaches 2.25%.

- With this in mind, we expect a terminal rate of 2.0% by the Fall of 2025, implying a further 125bp reduction in the policy rate, supported by our expectations that inflation will remain consistent with the BoC’s target. The balance of risks to this view is skewed to the downside.

- There is considerable uncertainty regarding our view of the terminal rate, given the uncertainty surrounding the economic outlook for 2025. A partial implementation of the new immigration targets would lead to a higher terminal rate, while U.S. tariffs on imports from Canada would send it lower.

- The U.S. imposing tariffs on imports from Canada is a major risk to the outlook, as it would most likely push the Canadian economy into a recession. The resulting downturn could be particularly severe if it results in significant layoffs, given the impact of income losses on already financially strained households.

- In both scenarios where Canada retaliates or doesn’t to the U.S. tariffs, the BoC would, in our view, cut its policy rate to support growth and look through the temporary inflationary impacts of tariffs and the associated Canadian dollar depreciation on inflation.

- The political goal of these tariff threats appears to be to extract concessions from Canada on sources of irritants to the U.S., such as the supply-management system, digital tax on big tech firms and insufficient defence spending. Nevertheless, they need to be taken seriously.

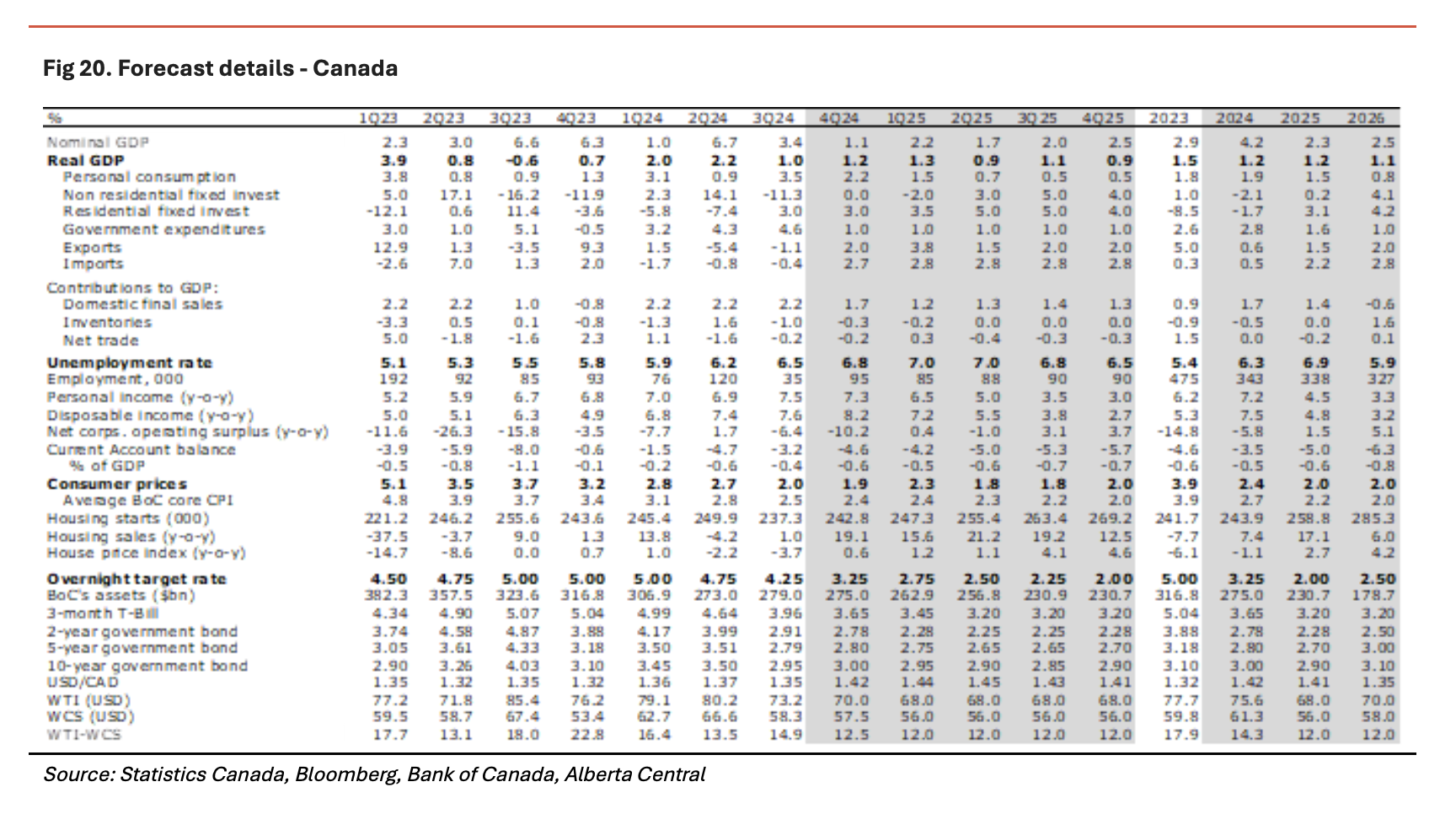

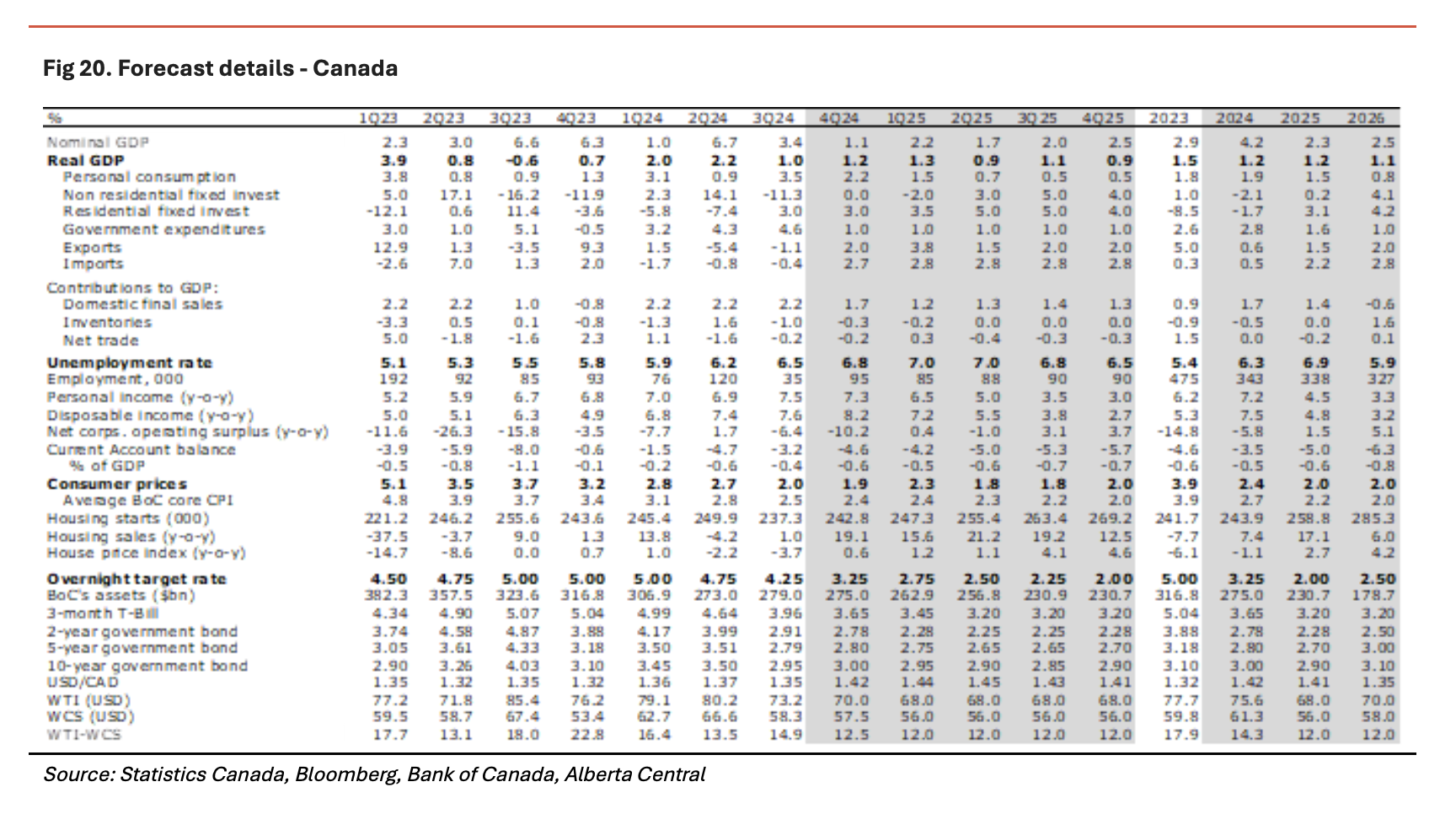

- The Canadian economy is expected to grow by only 1.2% in 2025, as it is held back by slower population growth.

- Inflation is expected to remain consistent with the BoC’s inflation target and hover close to 2% for most of 2025, while core inflation is expected to ease slightly.

- In Alberta, growth is expected to grow by 2.3%, with a slower population growth holding back the economy; nevertheless, Alberta will remain one of the fastest-growing provinces in 2025. The opening of the TMX pipeline will continue to boost the economy with a continued increase in oil production and a further rise in oil exports. However, Alberta’s economy is the most vulnerable to U.S. tariffs amongst Canadian provinces.

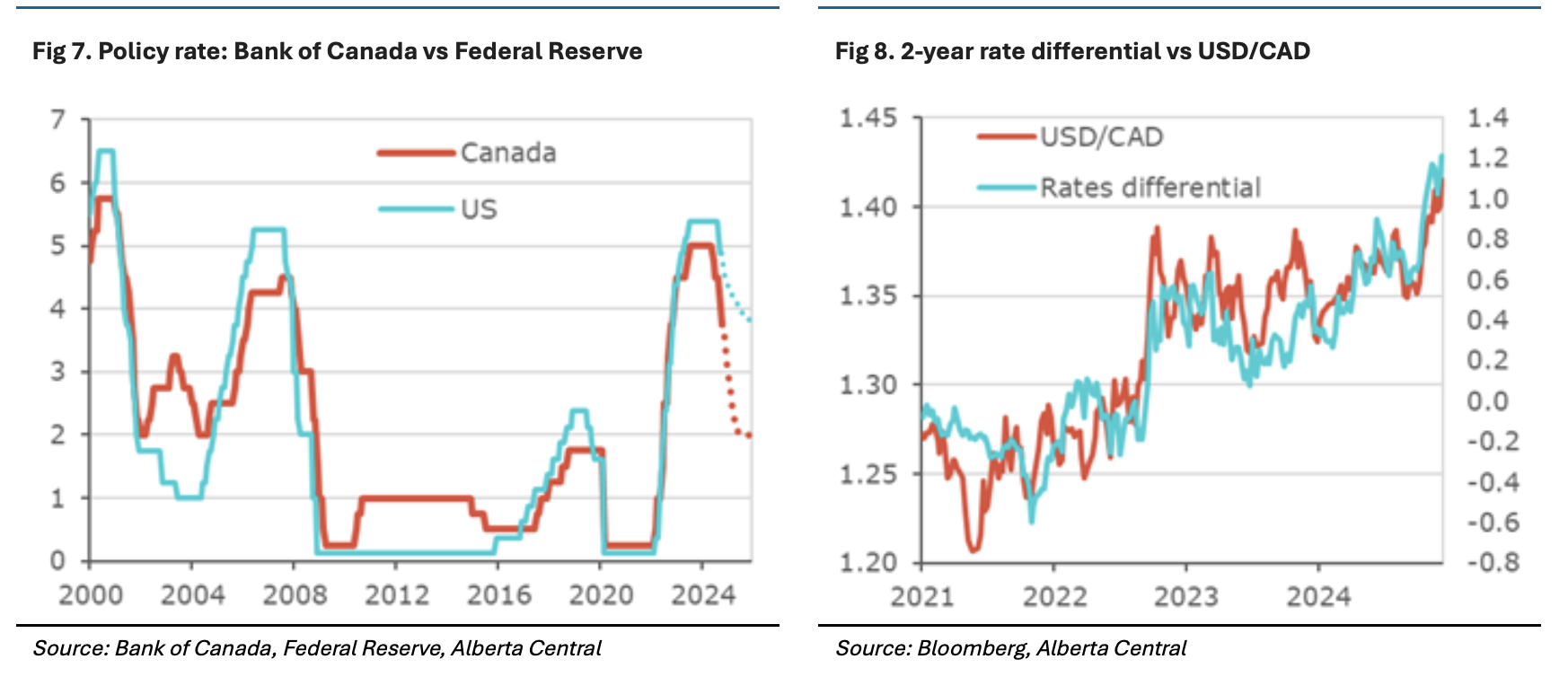

As global inflation continues to ease in 2024, the year has been marked by the beginning of an easing cycle, with most major central banks reducing rates; for example, the Federal Reserve cut its rate by 75 basis points (bp) so far, the European Central Bank by 100bp, the Bank of England by 50bp, and the Bank of Canada by 175bp, with many other central banks following suit.

In 2025, the central banks of most advanced economies are expected to continue to ease monetary policy. However, while the direction for the policy rate is clear, there is significant uncertainty regarding the extent of expected rate cuts; more specifically, the terminal rate at which central banks will stop easing monetary policy.

This year’s economic outlook explores the search for Canada’s terminal rate, with consideration of external factors such as new immigration targets, relations with the United States, etc., as well as broader trends within the global, national and provincial economies.

What is the neutral rate and how is it linked to the terminal rate?

A key factor that will determine the terminal rate in the current easing cycle will be the level of the neutral rate. This is crucial because the neutral rate determines the policy stance of monetary policy.. With this in mind, the terminal rate could be below neutral if a central bank needs to stimulate the economy or above neutral if monetary policy is needed to remain restrictive.

However, there is significant uncertainty regarding the level of the neutral rate because it is unobservable and needs to be estimated. This is why BoC Governor Macklem recently said that the central bank may need “to discover” where neutral is. This leads to considerable uncertainty regarding where the terminal rate will be in the current easing cycle.

This uncertainty is also exacerbated by the fact that economic literature often refers to two definitions for the neutral rate (see Mendes, 2014).

Medium- to long-run: This is the rate of interest that should prevail after the effects of business cycle shocks have dissipated. This concept of the neutral rate would be influenced by medium- to longer-term forces such as demographic change. Deviations of the actual policy rate from this measure of neutral are used to gauge the stance of monetary policy. This is the definition the BoC or the Federal Reserve uses when they release their estimate for the neutral rate or r*.

Contemporaneous: Popularized by Woodford (2003), this is the rate of interest that would ensure an output gap of 0 in every period. It is more useful as an indicator of the policy rate that is warranted by current economic conditions rather than as a benchmark against which to gauge the degree of policy stimulus.

As the first measure is very helpful in providing a longer-term anchor for interest rates once the economy is at the steady state, it is used for this purpose in the BoC’s models. The second measure provides an estimate of where the policy should be considering all the shocks affecting the economy. It is essential to note that both measures are intimately linked. When the contemporaneous neutral rate fluctuates because of an economic shock, it will return to the medium-to-long-term rate once the shock dissipates; this is true unless the shock permanently impacts the long-term equilibrium of the economy.

For example, a significant depreciation of the Canadian dollar would push economic activity higher through exports and raise inflation due to higher import prices. This would raise the contemporaneous neutral rate required to balance the economy and return inflation to target, necessitating higher interest rates to remove excess demand. As the shock works through the economy, interest rates would gradually return to the medium- to long-term neutral rate.

The contemporaneous measure can also deviate from the medium-to-long-term measure for extended periods due to economic shocks. For example, after the global financial crisis, the continued negative shock to the Canadian economy from weaker U.S. and global growth meant that the policy rate remained well below the medium-to-long-term neutral rate without creating inflationary pressures.

Although many analysts focus on the BoC’s range of 2.25% to 3.25% for the terminal rate, this overlooks the impact of shocks that could temporarily move the neutral rate. Instead, a macro framework based on a neutral rate that can vary in the short term due to shocks before converging gradually to a long-term anchor is preferable.

As Governor Macklem has recently said, the neutral rate is only revealed under ideal conditions – when there are no shocks on the economy, the output gap is 0, and inflation is at target – arguably, conditions that “will never happen.” This comment suggests that the governor may also believe that the neutral rate could vary from the BoC’s estimate in the short term.

What determines the neutral rate?

The neutral rate is the interest rate that balances an economy’s investment needs and its level of savings. In other words, it is the interest rate at which the demand for funds (investment) equals supply (savings). As such, an increase in investment demand pushes the neutral rate higher, while more savings pushes the neutral rate lower. Countries with open financial markets are affected by the global neutral rate since any shortfall in national savings will need to be covered by foreign savings and vice-versa.

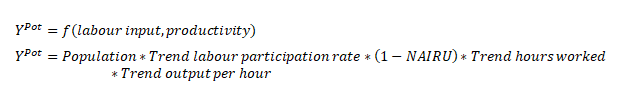

One of the key determinants of the neutral rate is potential growth, which is determined by productivity and labour input growth.

If the trend labour participation rate, NAIRU and trend hours worked are believed to be constant, potential growth is simply driven by population growth and labour productivity growth.

Productivity: Higher productivity growth increases the neutral rate as it raises the expected return on investment. As productivity improves, businesses invest more to capitalize on new opportunities, which drives up the demand for funds and, consequently, the neutral interest rate.

Declining productivity growth in recent years has dragged the neutral rate. Although labour productivity may improve over the next two years due to weaker population growth and recent immigrants becoming more integrated into the economy, it is unclear whether these improvements will be sufficient to fully reverse the negative impact from other factors – most notably, the significant demographic change.

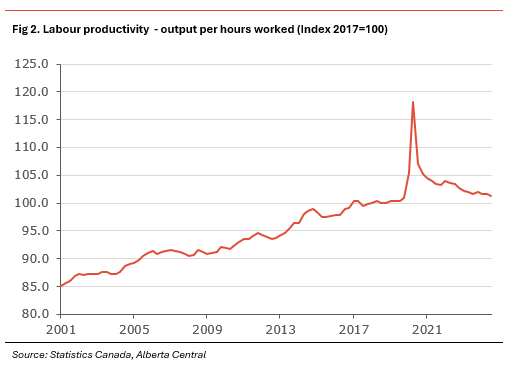

Labour input: Faster population growth increases potential growth and the neutral rate as it raises investment needs in the economy, such as for infrastructure. In addition, changes in demography may influence the neutral interest rate; for example, an aging population may lead to higher savings for retirement, thereby increasing the supply of loanable funds and lowering the neutral interest rate. Similarly, an increase in NAIRU or a decline in the participation rate may also reduce the neutral rate due to its drag on growth.

Strong population growth in recent years has pushed the neutral rate higher. This impact likely explains why, despite interest rates being well into restrictive territory, the economy did not fall into a recession as many observers, myself included, expected in late 2023.

A sharp reduction in immigration due to the new government’s immigration targets will significantly slow Canada’s population growth. Consequently, the Canadian population is expected to decline by about 0.2% in both 2025 and 2026; most of the decline will be due to a sharp reduction in the number of non-permanent residents in the country. This would be the first time since data became available in 1922 that Canada’s population will not increase. Such a change could more than reverse the increase in the neutral rate due to demography seen in recent years.

With population growth much weaker than expected, the contribution from labour input to growth will be close to 0 unless there is an improvement in other structural determinants of labour inputs.

Other factors influencing the neutral rate are:

Government borrowing: Government borrowing can affect the neutral interest rate through changes in the demand for funds. For example, expansionary fiscal policy, characterized by increased government borrowing, can raise the neutral interest rate by boosting demand for investment funds. While various levels of government are currently running deficits, the size of the government borrowing required to cover this demand remains relatively small and has a very marginal influence on the neutral rate in Canada.

Global savings: The neutral interest rate is not merely a domestic phenomenon for countries with access to global financial markets. As such, global capital flows mean that financial conditions abroad can influence domestic neutral rates. For instance, higher global savings can put downward pressure on domestic neutral rates. This was the case during the 2000s when excess savings from China drove global interest rates lower, a period that was called the “Global Saving Glut.”

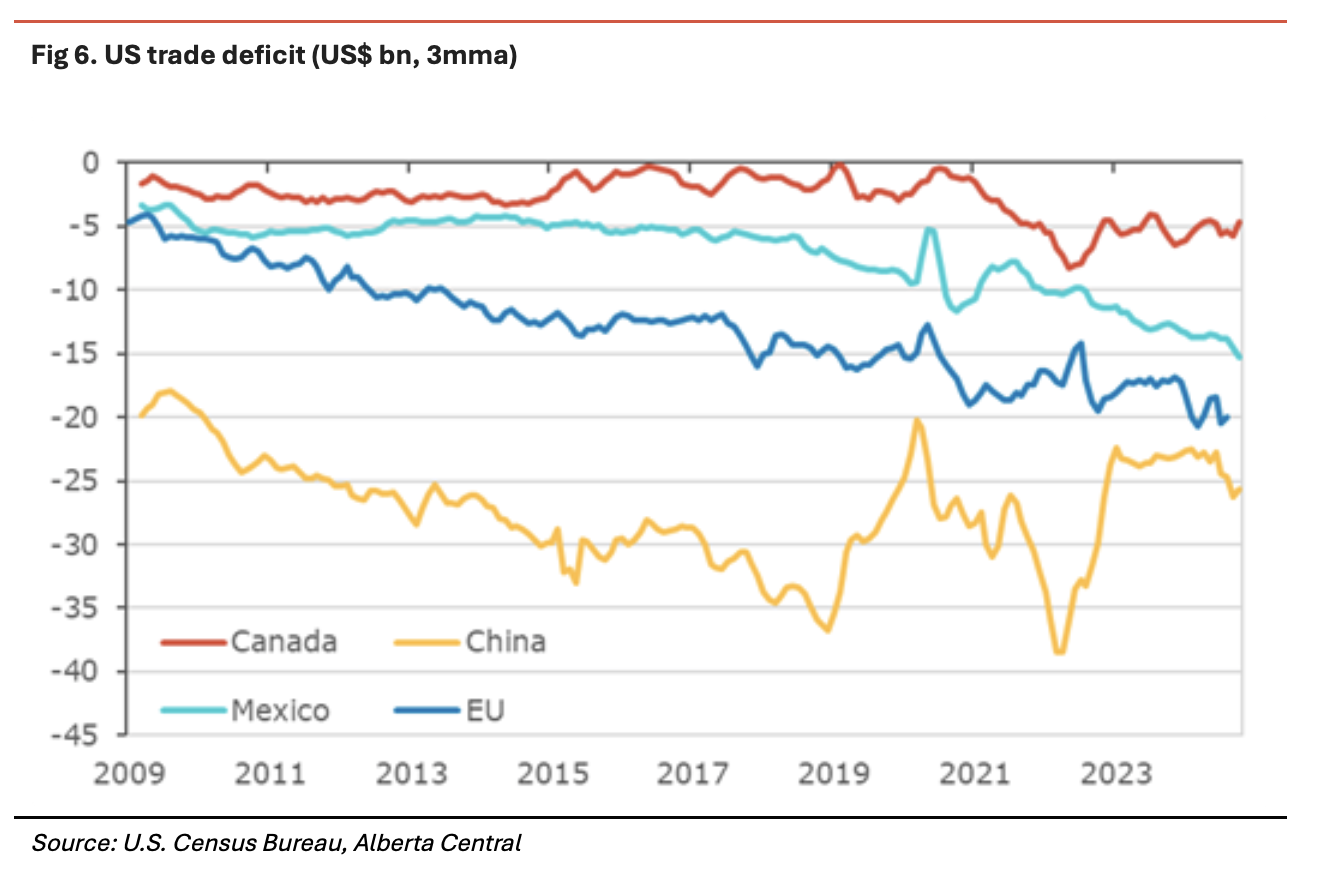

The current state of the demand and supply of global savings suggests some upside pressures on the global neutral rate. China and oil exporters, both of which are big sources of excess savings in recent years, are expected to have smaller current account surpluses in coming years. On the flip side, in the U.S., continued large fiscal deficits of approximately 6% of GDP indicate that the U.S. government will continue to borrow heavily. Moreover, the country is expected to continue to run a large current account deficit, which foreign inflows must finance.

In addition to these factors, potential growth in the U.S. is expected to remain robust in the coming years, at 2.2% according to the BoC, supported by continued strong productivity growth and increases in labour input, as population growth remains robust, supported by an improvement in immigration.

All these factors suggest that the global neutral rate could be slightly higher in the coming years.

The propensity for households to save vs borrow: Whether households have a preference for borrowing rather than saving will lead to a higher neutral rate. In this situation, there is a higher demand for borrowing rather than for saving. The reverse is also true; a higher preference by households to save will push the neutral rate lower.

High household debt levels make the sectors sensitive to interest rates. As we have seen since the Bank of Canada started increasing interest rates in early 2023, households have increased their savings as they dedicate a more significant share of their income to debt repayment, thereby pushing the neutral rate.

However, there is some uncertainty regarding what will happen to households’ savings behaviour as the BoC continues to lower its policy rates in the coming year; we could likely see an increase in household borrowing and a reduction in the saving rates, pushing the neutral rate higher.

Financial market conditions: Lenders’ increased risk aversion can lead to a lower neutral rate. As such, an increase in credit spreads or lending spreads would mean that the policy rate needs to be lower to provide the same level of interest rates to the private sector – whether it’s businesses or households. This increased uncertainty that could come from the governing style of the newly elected Trump administration could lead to increased risk premiums. However, we have yet to see a meaningful widening in credit spreads.

The impact of new immigration targets on the economy and the neutral rate

The federal government recently announced drastically lower immigration targets for 2025, 2026, and 2027 through a reduction in the number of new permanent residents. The reasoning behind this policy decision is to ease pressure on the country’s housing market, infrastructure and public services. This will impact the economy’s supply side by slowing growth in labour input and potential growth; however, the demand side of the economy will also be affected.

Consumer spending

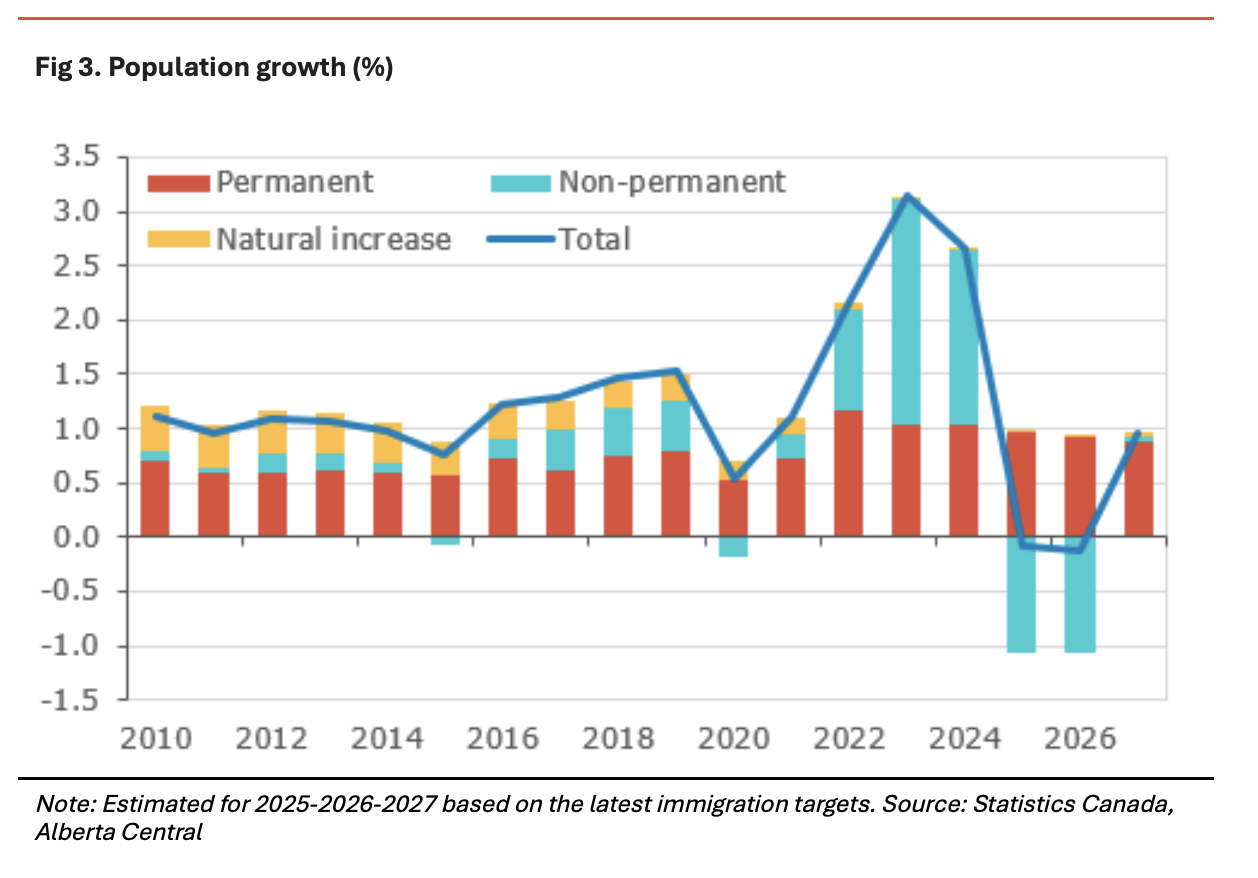

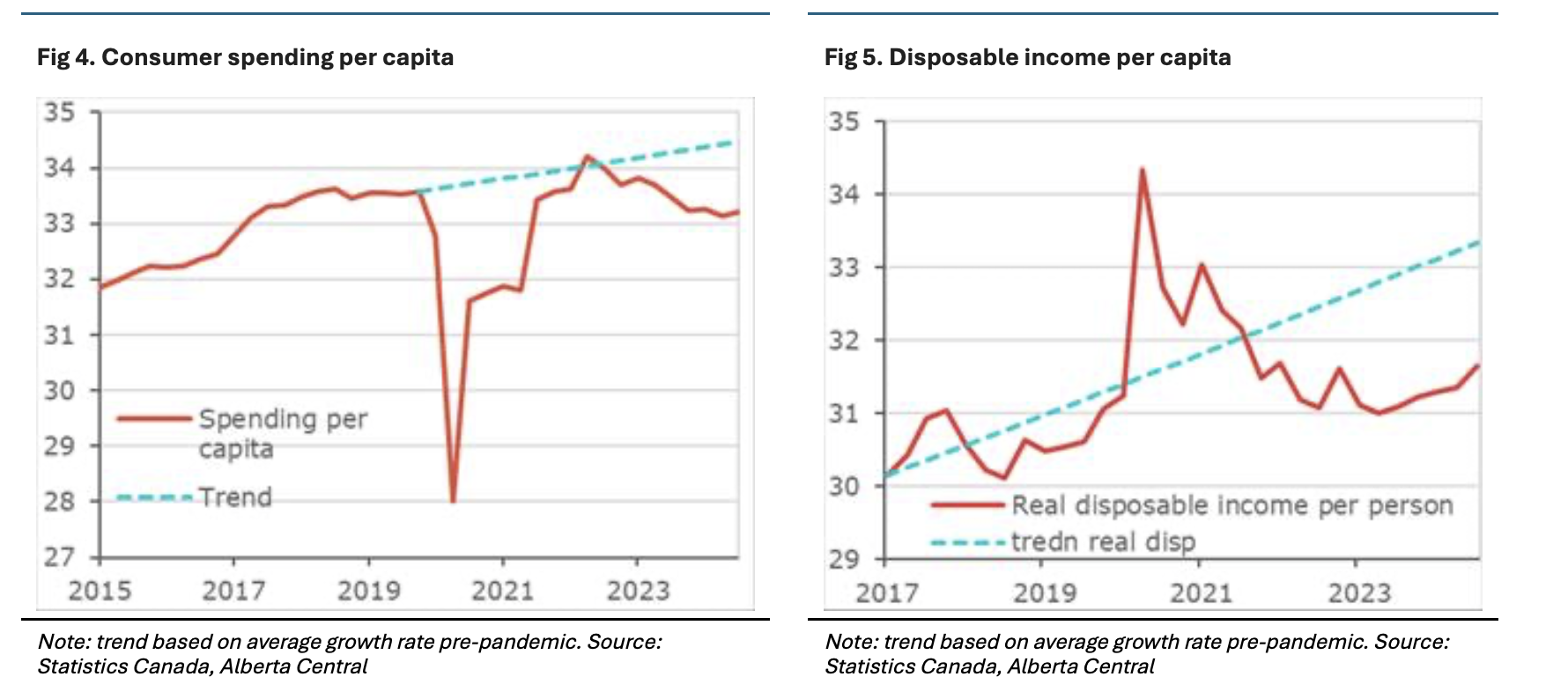

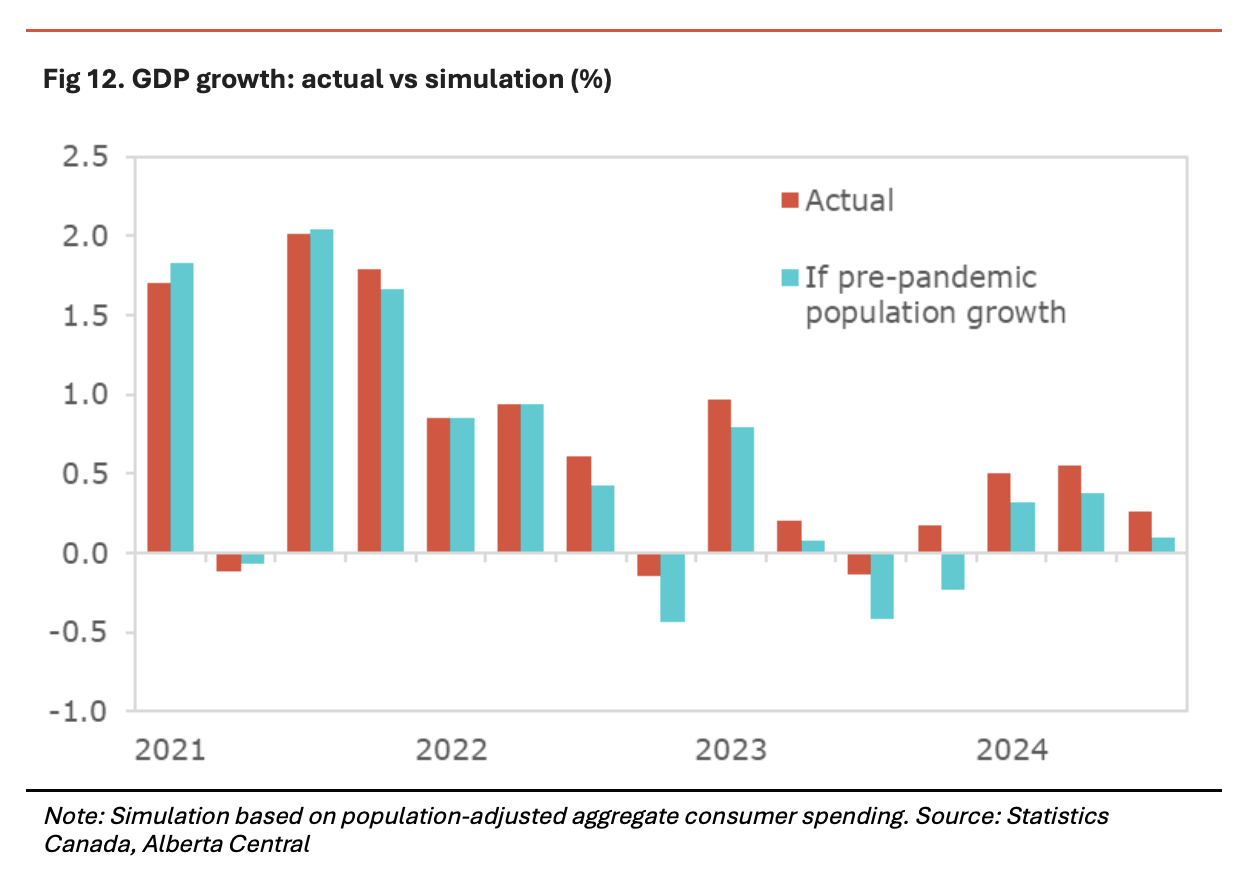

The sharp increase in population in recent years can be fully credited for helping the Canadian economy to avoid a recession (see It’s a “Me-cession”, not a recession).

The current situation can be referred to as a “Me-cession.”;collectively, we are spending more and pushing economic activity higher, but individually, we restrict purchases and behave as though in a recession. Recent data on consumer spending shows that individuals are still restraining their spending, with real consumer spending per capita having declined six times over the past nine quarters. As a result, real expenditure per capita is about 1.1% below its pre-pandemic level and 3.6% below its peak in early 2022, prior to the BoC’s tightened monetary policy.

This underperformance in spending per capita is partly due to a stagnation of households’ purchasing power. Adjusted for inflation, disposable income per capita is only 1.9% higher than pre-pandemic levels; it is about 5.5% below where it should be if it had continued to increase at its pre-pandemic trend. This underperformance in purchasing power and its impact on consumer spending may also be explained by higher food prices and shelter costs – a major source of inflation in recent years.

A small decline in population growth over the next two years means that the contribution to growth from aggregate household spending will be fully determined by the change in real spending per capita. Hence, unless individual households begin to increase their individual levels of spending, consumer spending will remain weak.

Labour Market

Recent population growth has impacted the labour market as well. In fact, most of the rise in the unemployment rate is attributed to more workers entering the workforce than the economy was able to absorb. The strong population growth has also contributed to the labour market’s resilience. With aggregate demand continuing to increase because of a larger population, most businesses have averted a decline in overall activity. Hence, they still require the same number of workers as before, thus preventing layoffs and reducing the risk of a hard landing (see Will it be a hard landing or a soft landing? The labour market will decide).

The reduction in the supply of workers over the next two years should help rebalance the labour market, gradually reducing the number of job seekers. However, this will depend on the demand for labour. As previously mentioned, job creation has remained positive in recent years because the economy continued to expand thanks to strong population growth. The rate of expansion may stall if consumers and other sectors of the economy do not grow. This could lead to an underperformance in hiring and possibly job losses next year.

Housing

A decline in the number of non-permanent residents in Canada will affect the housing market; although weaker population growth broadly reduces demand for housing, the impact will be heterogeneous on various sectors of the housing market.

The direct and immediate impact a lower number of non-permanent residents will have on the rental market, as they are more likely to be renters than homeowners, given the temporary nature of their immigration status. As a result, we should expect downward pressures on rents in urban areas, especially those with a large number of non-permanent residents.

A decline in rent is likely to spill over into s the condo market through two channels; due to their higher prices, the single-family segment of the market is likely to be less affected and remain mainly influenced by changes in affordability.

1) Prospective buyers who are currently renting may delay their purchase of a home, reducing demand. Given their lower price points, condos will see the biggest impact.

2) Many investors have purchased condos in recent years to rent and take advantage of fast-rising rents and increasing home prices. However, stagnating or declining rents will lower the return on investment and could force some of these investors to sell, increasing the supply of condos on the market.

Home building may be affected, too; declining rents and weaker demand for condos will reduce the incentive for developers to build new housing units, especially multiple-unit dwellings. Consequently, the country may fall further behind on its aggressive home-building target, leading to a further lack of supply and unaffordability. With low supply, demand will remain the main driver of house prices.

Potential growth

Declining population growth will ease potential GDP growth unless other components of labour input increase or if labour productivity improves meaningfully. The lower potential growth will mean that the excess capacity in the economy could be reduced more rapidly than expected, depending on GDP growth.

In its latest Monetary Policy Report, the BoC expects potential growth to slow from 2.4% in 2024 to 1.9% in 2025 and 2026. This projection is based on weaker population growth but does not incorporate the full impact of the new immigration targets, while an expected improvement in labour productivity offsets some of the effects of weaker population growth.

New immigration targets suggest that labour input is likely to be close to 0 in 2025 and 2026 instead of 0.9pp and 0.6pp, as estimated by the BoC, respectively. If trend labour input (i.e. participation rate, NAIRU and hours worked) is unchanged, potential growth will only increase thanks to improvements in labour productivity. Although slower population growth may lead to productivity improvements over the next 2 years, continuous underperformance in recent years suggests that a rebound in productivity will be modest and likely insufficient to reverse a slowdown in potential growth.

Given the BoC’s most recent estimate of potential growth, labour productivity is expected to contribute 0.8pp in 2025 and 0.9pp in 2026. With labour input unchanged over this period, it means that it is very likely that potential growth will be below 1% over the next 2 years, below the BoC’s estimates of 1.9% for both years.

The threat of tariffs

President-elect Donald Trump’s announcement to impose 25% tariffs on imports from Canada and Mexico – which may be negotiation tactics – raises uncertainty for next year’s economic outlook.

As 75% of Canadian exports are to the U.S. – 25% of Canada’s GDP – proposed tariffs would significantly impact Canada’s economy. According to a recent report by the Canadian Chamber of Commerce (see), “over three-quarters of our bilateral trade with the U.S. is business inputs, such as manufacturing parts, energy and capital goods”; therefore, as a significant share of Canadian exports to the U.S. are made with American inputs, there would be consequences for both trading partners.

Regardless of the perspectives of Trump’s advisors on the impact on the U.S. economy, the cost of tariffs on Canadians will be comparatively higher; University of Calgary economics professor Trevor Tombe estimated for the Canadian Chamber of Commerce that proposed tariffs would lead to a 1.8% decline in GDP with no retaliation and a reduction of 2.6% with retaliation (see). In comparison, the impact on the U.S. economy is estimated at -1.0% without retaliation and -1.8% with retaliation. With expected growth next year of 1.2%, 25% tariffs on U.S. imports from Canada would push the Canadian economy into recession.

The resulting recession could be particularly severe if it results in significant layoffs. There are an estimated 1.2 million Canadian jobs that would be directly affected by the tariff (see). Job losses and the associated drop in income could cause important negative spillovers to the economy, especially due to its heavy strain on household finances. Specifically, forced selling in the housing market, as households who can no longer make their payments sell their homes. The subsequent influx of new listings could drastically change the housing market’s equilibrium at a time when demand is also likely to be weaker.

Moreover, a drop in income would likely lead to a rise in defaults and losses at financial institutions. This would lead to lenders turning risk-averse to protect their balance sheets and reducing credit availability to households and businesses, likely leading to higher borrowing costs. The resulting credit crush would harm business investment, consumer spending and the housing market as it would be more difficult to obtain a mortgage.

As the economy slows further due to these factors, there is a risk of further job losses and financial strains on some households, exacerbating the downturn and leading to a deeper recession.

The broader economic impact may also include a depreciation of the Canadian dollar, although the exchange rate may act as a pressure valve, absorbing some of the impact from tariffs, thereby assisting Canadian exports to remain competitive. Nevertheless, a weaker currency would likely increase inflation by making imported goods more expensive.

Without retaliation, the BoC would likely cut its policy rate in response to output losses. In the case of retaliation, economic models suggest that the BoC would hike its policy rate to respond to higher inflation. However, the resulting inflation would be temporary. Similar to a tax hike, as tariffs would be a shift in price levels, it is likely that the BoC would focus on permanent output losses instead of temporary inflation. Consequently, the BoC could be expected to deviate from the models’ prescription by keeping rates unchanged or even reducing them.

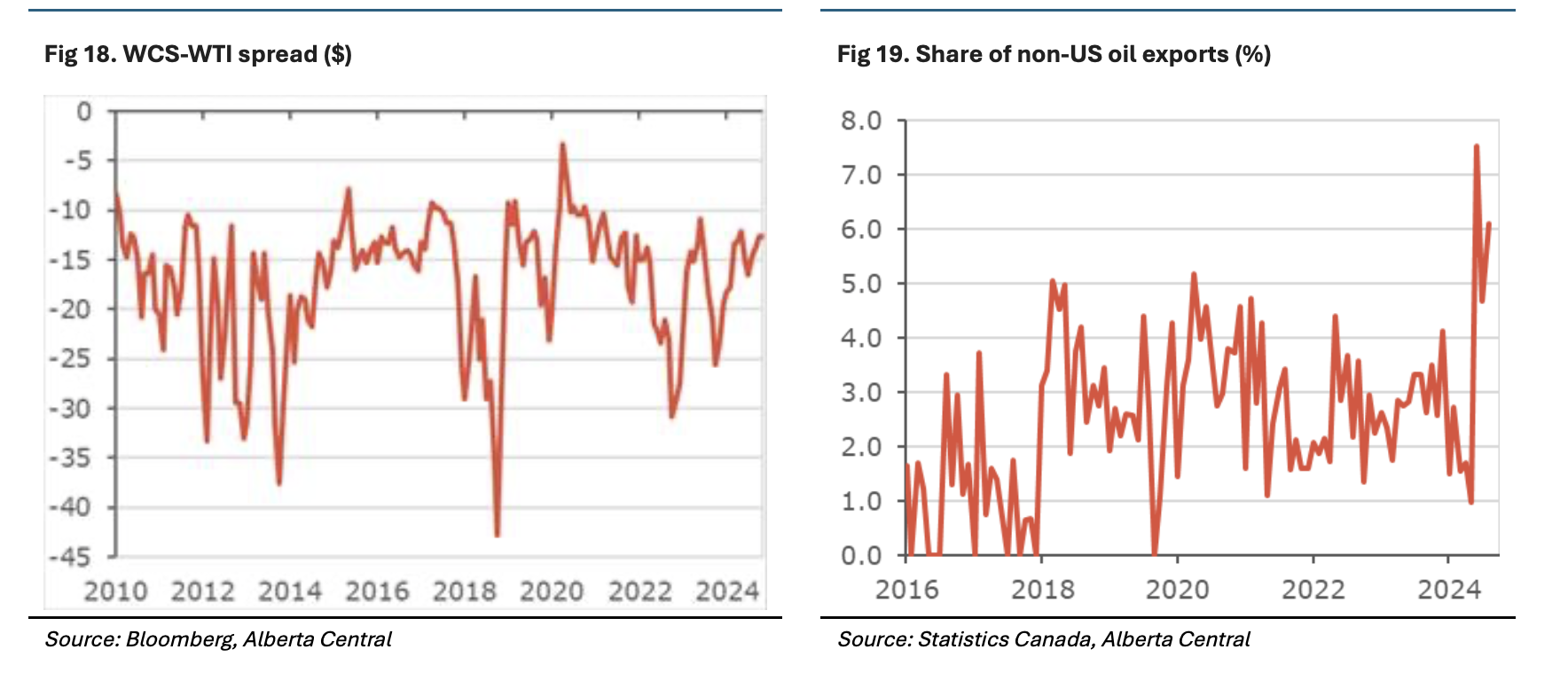

An oft-forgotten topic regarding the economic impact of tariffs is who will ultimately bear its costs. Due to thin profit margins, for manufacturing goods, exporters would absord these costs. For energy exporters, given almost 90% of domestic oil production is exported to the U.S., there could be an incentive for Canadian oil producers to absorb some or all of the tariffs by lowering their selling price (with an impact similar to a widening in the WTI-WCS spread) to avoid the U.S. from seeking a new source for oil imports, such as Venezuela.

The political goal of these tariff threats appears to be to extract concessions from Canada on sources of irritants to the U.S., such as the supply-management system, digital tax on big tech firms and insufficient defence spending.

However, the threat of tariffs extends beyond Canada; as President Trump has mentioned many times, China is likely to be its main target. However, with European countries on his radar, the impact of these tariffs on the global economy shouldn’t be underestimated.

Where is the terminal rate, then?

It is unclear whether the shock to population growth will lead to more or less excess capacity in the Canadian economy. Both the demand and supply sides of the economy will be impacted, with the resulting impact on the output gap dependent on which adjusts faster and its extent. Nevertheless, what is certain is that economic growth will be much weaker in 2025 and 2026 than initially expected; consequently, as there will be very little room to maneuver between economic expansion and contraction, the likelihood of a recession is higher.

Weaker potential growth in 2025 and 2026, likely below 1% in both years, suggests that the neutral interest rate for this period will likely be below the BoC’s estimates. However, the deceleration in population growth is likely to be gradual, and so will a decline in the neutral rate, thereby allowing the BoC to adjust its policy rate progressively. Moreover, implementation risks regarding new immigration targets mean that we shouldn’t fully incorporate the impact of the weak population growth. In addition, external factors, such as significant government borrowing in the U.S., could exert some upward pressure on the neutral rate in Canada.

As the downside pressures on the neutral rate are dominant, the neutral rate will be lower over the next two years, around or even slightly below the lower bound of the BoC’s estimate of 2.25%. This has significant implications for monetary policy, as it suggests conditions to remain in restrictive territory until the policy rate reaches 2.25%.

With this in mind, we expect a terminal rate of 2.0% by the end of 2025. This implies that the BoC will cut its policy rate by another 125bp; 25bp cut at each meeting until it reaches 2.5% in April 2025. Subsequently, the BoC will cut two more times at a slower pace in July and October 2025.

The continuation of the easing cycle is supported by our expectations that inflation will remain consistent with the BoC’s target in 2025, despite some modest increase in early 2025 due to a base effect.

However, there is considerable uncertainty regarding our view of the terminal rate, given the uncertainty surrounding the economic outlook for 2025. The balance of risks may be leaning toward a lower terminal rate, especially if the incoming U.S. Administration were to impose tariffs on imports from Canada. Conversely, a partial implementation of the new immigration targets would lead to a higher terminal rate, while a full implementation could push it lower

In the U.S., the BoC estimates that the U.S. medium-to-long-term neutral rate is between 2.25% and 3.25%, the same as in Canada. The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) latest projections suggest a range between 2.5% and 3.5%. There are a lot of signs pointing to a neutral rate in the U.S. that will be higher than in Canada in the coming year. Strong productivity gains and increases in labour input due to a higher participation rate and immigration are pointing to robust potential growth. Moreover, the federal government’s continued elevated levels of borrowing also suggest some upside pressures on the neutral rate. With this in mind, we believe that the terminal rate in the U.S. is likely closer to the top of the estimated range of 3.625%.

The divergence in the neutral rate between Canada and the U.S. will further widen the policy rates of both countries; this bigger spread will continue to be a drag on the value of the Canadian dollar. However, further depreciation may be limited since there is already almost 100bp of cut priced in for the Federal Reserve and nearly 125bp for the BoC over the next year. Nevertheless, given our view on respective policy rates, we think further modest depreciation in CAD is likely, reaching 1.45 in mid-2025.

2025 Outlook

Global economy

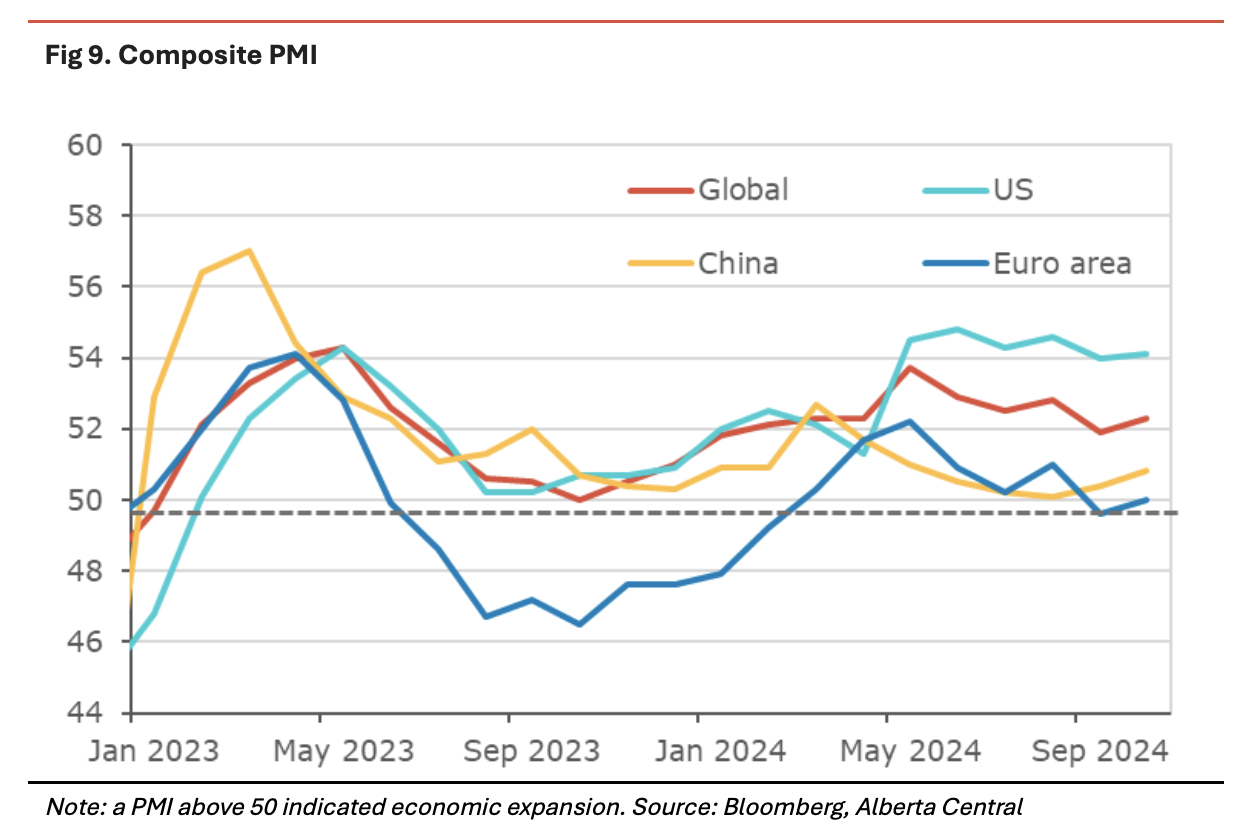

The outlook for the global economy is cautiously optimistic for 2025. According to the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook, global growth is expected to remain at 3.2% in 2025. However, the relative stable growth on the surface hides divergence between regions and countries. The European Union, Japan, Canada, and the UK are expected to see an improvement in growth, while the U.S., China, India, and Brazil should see slower growth next year. Inflation is to continue to gradually normalize in many countries, which will lead to further monetary easing by many central banks.

Eurozone

European economies have generally underperformed in 2024, growing by a modest 0.8%. While growth is expected to improve in 2025, it is expected to be 1.2%. The export sector has been notably weak. The manufacturing sector continues to struggle due to adjustments to the past energy shock, weak productivity and strong global competition; these challenges are particularly acute in Germany. On the flip side, economic improvements are expected to arise from stronger domestic demand.

Inflation has decelerated towards the European Central Bank’s (ECB) 2% target. Most of this deceleration is due to lower energy prices, while service price inflation has been stickier at around 4%. Nevertheless, core inflation, which excludes food, energy, alcohol, and tobacco, is now at 2.7%.

A deceleration in inflation and underperforming growth have allowed the ECB to reduce its policy rate. Since June 2024, the ECB has cut its main refinancing rate by 110bp from 4.50% to 3.40%. Financial markets expect further monetary policy easing in 2025, with the ECB expected to cut interest rates by 160bp in the first half of 2025 to 1.50%.

China

Economic activity in China slowed in 2024 to 4.8% from 5.2%, much lower than its pre-pandemic average. This weakness is due to the continued impact of the ongoing downturn in the property market and its drag on the domestic economy. As such, falling house prices have been holding back consumer and business confidence, leading to weak retail sales and business investment.

In the first half of 2025, its domestic economy is expected to remain soft but improve mid-year as recent policy actions and announcements will gradually provide fiscal and monetary stimulus to the economy. Moreover, a continued increase in production capacity, declining prices for Chinese goods and improved demand in industrialized countries should support exports. Nevertheless, growth for the whole year is expected to be lower than in 2024 at 4.5%.

Slower growth in China will have broader implications for the global economy. The weakness in China’s domestic demand will lead to weaker demand for key commodities, especially oil. As a result, global commodity prices are expected to remain under pressure in 2025.

U.S.

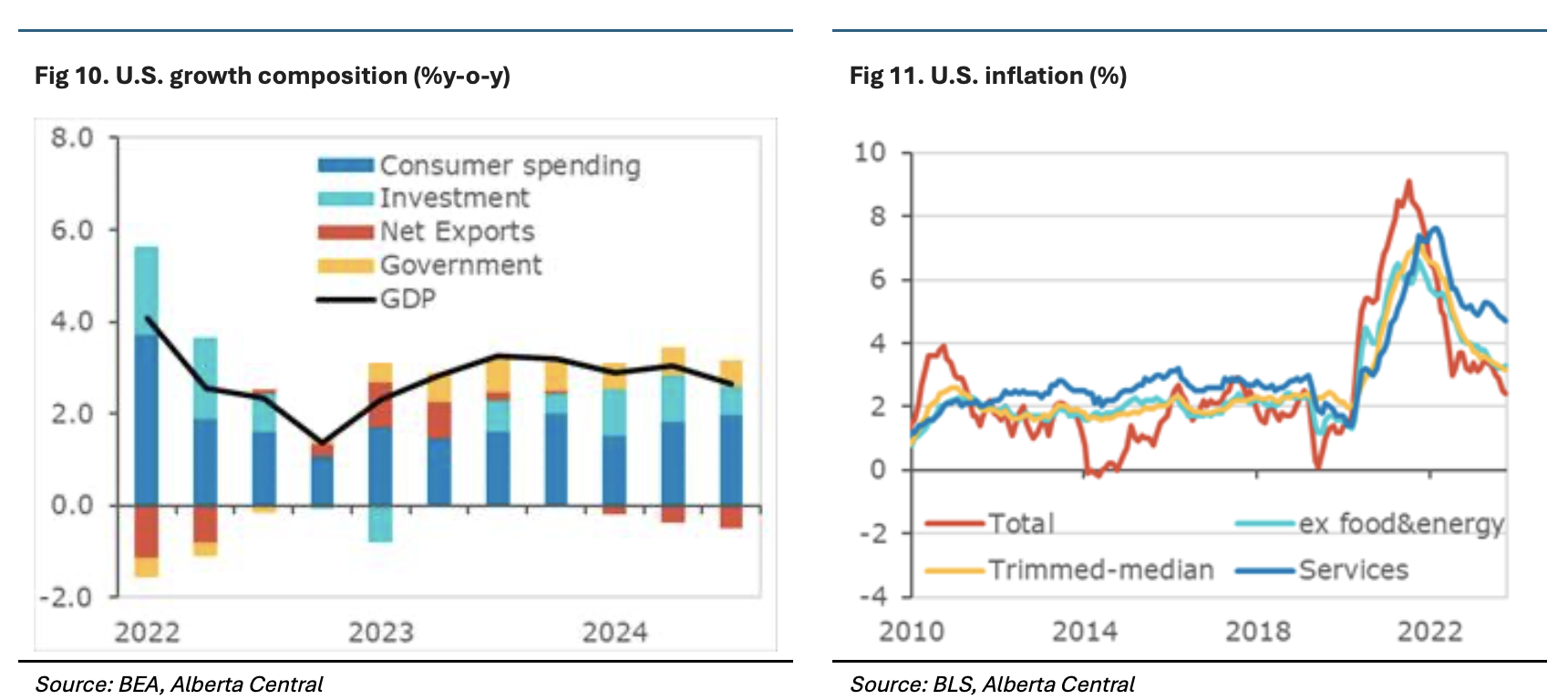

The U.S. economy significantly outperformed other industrialized countries in 2024, with estimated growth of 2.8%. Rising financial wealth, easing financial conditions and rising purchasing power supported consumer spending. This economic strength is mostly attributed to fiscal stimulus, with the government fiscal deficit reaching about 6% of GDP. Private business investment remains strong, supported by government incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the CHIPS and Science Act.

While demand has been strong, improvements on the supply side have meant that the level of excess demand has remained contained and allowed inflationary pressures to ease. As such, labour productivity growth in the U.S. has outperformed other industrialized economies, and labour inputs have increased thanks to a return of the participation rate to its pre-pandemic level and stronger immigration.

U.S. growth is expected to moderate in 2025 to 2.2%, as the impact of government incentives on business investment fades and there is potentially lower government spending. However, there are several downside risks to growth, including the imposition of import tariffs, which could lead to higher prices and reduce consumer spending. Conversely, lower interest rates and continued strong demand could support the housing sector, while strong productivity growth will remain a tailwind for the economy.

Inflation in the U.S. has moderated over the past year, with the current personal consumption expenditure deflator (PCE) at 2.4% – closer to the Federal Reserve’s target of 2.0%. However, much of this deceleration is due to lower energy prices, and there remain some concerns that inflation may be persistent. As such, core PCE (ex. food and energy) has been stickier, remaining close to 3%. Similarly, service price inflation has been above 4% for most of 2024.

With growth expected to slow next year and robust labour productivity, excess demand is expected to shrink further; this would reduce inflationary pressures and lead to a further moderation in inflation. However, as mentioned, import tariffs are a significant upside risk to inflation, as importers are likely to pass the higher import costs to consumers.

With inflationary pressures moderating and growth slowing, the Federal Reserve is expected to reduce its policy rate at a modest and gradual pace; in 2025, we believe the Federal Reserve will cut its policy rate by about 75bp to 3.625%. A continued lack of deceleration in U.S. growth, or the inflationary impact of imports tariffs, could force the central bank to leave its policy rate higher than expected.

Canada’s economy

Many of the factors relevant to the global economy – as well as distinct policies within the national landscape, such as new immigration targets– will have a significant effect on the Canadian and Alberta economies.

Consumers: me-cession

As we have shown in “see It’s a “Me-cession”, not a recession” and “Faster cuts do not mean deeper cuts”, strong population growth has compensated for the weakness in per capita consumer spending. This weakness in consumer spending per person stems from the underperformance in household disposable income. As such, while disposable income per capita adjusted for inflation is currently 1.9% higher than on the eve of the pandemic, it has stagnated in recent years. In addition, a greater concern for consumer sentiment is how their current purchasing power compares to where it should be. With this in mind, real disposable income per capita is currently 5.1% below where it should have been if it had continued to increase at its pre-pandemic trend. The same is also true for households’ paychecks, with per capita employee compensation also well below where it should be.

Due to the underperformance in their purchasing power and the impact of higher interest rates on their finances, households have been restraining their spending. As a result, real consumer spending per capita has declined since early 2022. However, because of the increase in population, consumer spending increased in aggregate. In other words, while individual consumers are reducing their spending, collectively, we are spending more. We estimated that if the population had grown at its pre-pandemic pace, the reduction in per capita spending in late 2023 would have resulted in a recession. Similarly, growth in 2024 would have been about 1.1% q-o-q ar. on average rather than the 1.8% q-o-q ar. reported.

As we move into 2025, improvements in consumer spending are expected, supported by some modest improvements in purchasing power and lower interest rates. According to the latest national account numbers, real disposable income per capita may have bottomed in 2023Q2 and we expect a further increase next year. This improvement in purchasing power will support a gradual rise in real consumer spending per capita next year. Similarly, the latest retail sales data suggests that sales per capita adjusted for inflation could have bottomed out. Nevertheless, weaker growth in the population indicates that the contribution to growth from higher spending per capita will be modest but positive.

Housing

As mentioned previously, a lower number of non-permanent residents is likely to have a significant impact on the housing market, especially on the rental side and condos. Conversely, the market for single detached homes is likely to be much less affected and will remain heavily influenced by affordability; more precisely, the evolution of house prices, interest rates and household income.

While the BoC is expected to cut its policy rate by about 125bp between now and Fall 2025, the impact on mortgage rate may be limited. The variable rate, which is determined by the policy rate and a premium, will be lower, but the extent of any decline in the 5-year fixed mortgage rate is likely limited.This is because financial markets have already incorporated a significant easing by the BoC in longer-term interest rates, about 100bp over the next year. As such, at a level of about 2.60%, the 5-year swap rate already incorporates a significant reduction in the policy rate and any further decline would be limited.

Hence, while there are concerns that lower rates would ignite the housing market, mortgage rates are unlikely to fall meaningfully. A recession would be necessary for that, with consequences for the rest of the economy and the housing market, more specifically, in the form of increased layoffs leading to a decline in income and increased uncertainty.

Investment

On the residential side, investment has been lacklustre in recent quarters. This weakness is mainly concentrated in new construction and renovation, likely held back by the high interest rates, while ownership transfer costs have offset some of this weakness. Recent trends in housing starts suggest that new construction is unlikely to rebound rapidly despite lower interest rates. However, lower interest rates could further support housing transactions and lead to improvements in renovation spending. Declining rents and weaker demand for condos due to the decline in non-permanent residents are likely to reduce the incentive for developers to build new housing units, especially multiple-unit dwellings. However, the single-family segment is expected to be more resilient.

Considering the number of new homes that will be required over the next decade to improve affordability, investment in new residential will need to be much higher over the next few years. High financing costs, high levels of regulation and continued labour shortages in the construction sector are constraints to an increased supply of new homes. With the BoC cutting its policy rate over the next year, the hurdle caused by higher interest rates will ease. However, labour shortages are unlikely to decrease significantly over the next year, especially considering that the share of construction workers in total employment has never been so high.

The outlook for business investment also remains subdued. The latest business surveys continue to show that sentiment is weak, with businesses pointing to the weakness in domestic demand, elevated uncertainty, high borrowing costs and continued cost pressures for their bleak views. This is not an environment conducive to business investment and, as a result, investment intentions remain weak. Weaker growth next year due to the impact of lower immigration will further constrain domestic demand. Moreover, uncertainty regarding policy in Canada, as many business leaders await an imminent federal election, and the threat of tariffs is likely restraining business investment. Hence, any improvement in business investment next year will be very modest.

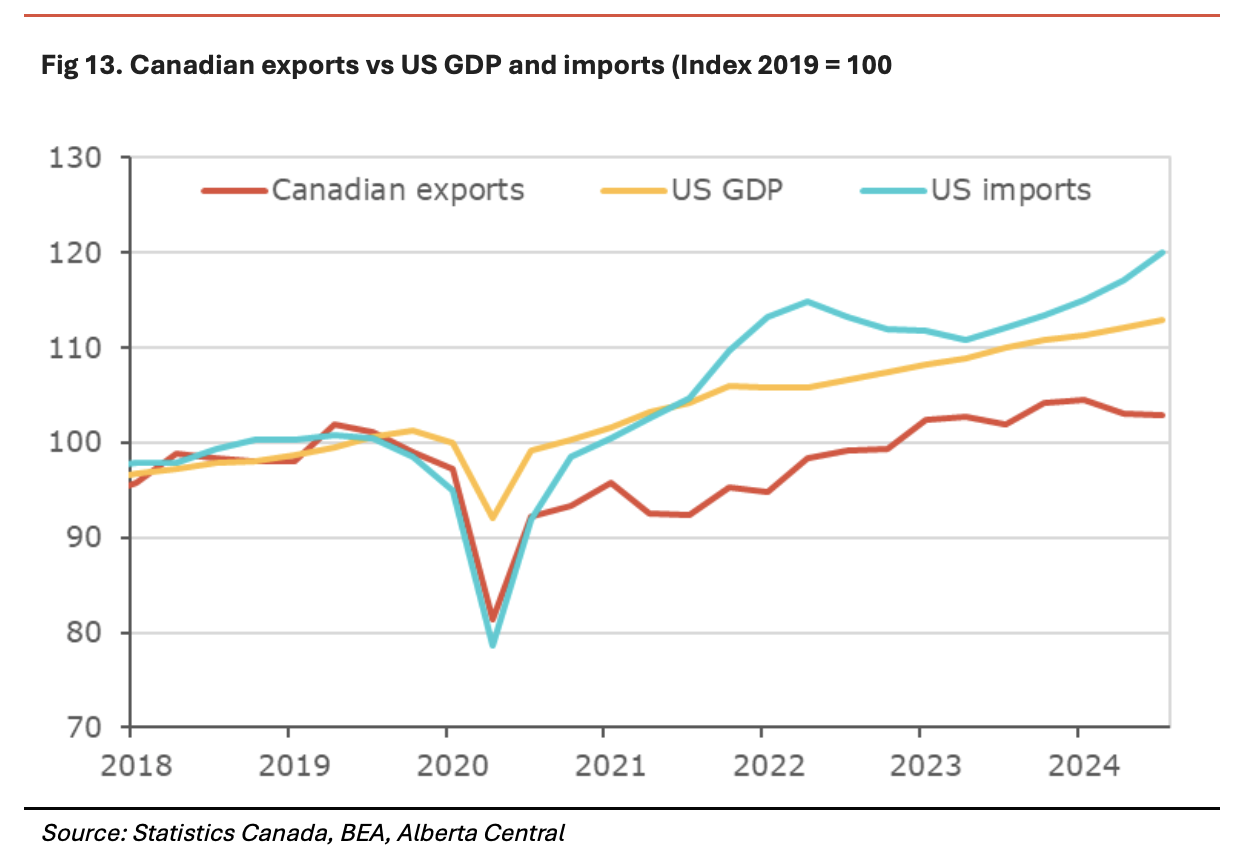

External sector

The lack of export growth so far in 2024 suggests that Canada is unable to capitalize on strength in the U.S. economy. Moreover, details show that while exports of commodities have increased modestly, exports of manufacturing goods have eased over the period.

The opening of the TransMountain pipeline will continue to positively impact exports in 2025. We estimated that the new pipeline capacity will increase oil exports by about 10% and could contribute about 0.25pp to growth over the next year. We have already seen the share of Canadian oil exports to non-US markets double since the pipeline’s opening. However, since this is a level shift in exports, the contribution to growth from TMX will fade away as its full capacity is reached. Similarly, the start of LNG Canada in mid-2025 will further push energy exports higher.

There are a number of risks on the horizon for Canadian exports; more specifically, the possibility of broad-based U.S. tariffs on imports from Canada, a return to more protectionist policies in the U.S. and a push towards de-globalization. However, reflecting on Canada’s experience during President Trump’s first term, when he imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum, exports are likely to experience a temporary short-term boost as U.S. importers stockpile Canadian goods ahead of the enforcement of broad tariffs.

Labour market

The performance of the labour market remains key to the resilience of the Canadian economy, with population growth having played an important role in supporting the labour market in 2024 and preventing layoffs in a lacklustre economy. As a result, continued growth in employment, albeit slower, and the lack of important job losses has meant that household income, while underperforming, has remained solid and has allowed households flexibility in absorbing higher interest rates and avoiding a wave of defaults.

Job creation has remained positive this year, with about 330k new jobs. Nevertheless, this is weaker than population growth, with the labour force increasing by almost double that number over the same period. With the labour market unable to fully absorb all newcomers into the labour force, the unemployment rate has been slowly drifting higher; currently, at 6.8%, this is 1pp higher than last year. However, while the increase in the unemployment rate has been important, there haven’t been significant layoffs so far; this means that the higher unemployment rate does not lead to lower household income.

Going into next year, we note some tentative improvements in hiring expectations. The most recent survey by the Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses (CFIB) shows that net hiring intentions are marginally positive, suggesting that, on balance, a small majority of businesses expect to increase their employment levels over the next 3 to 4 months. Similarly, the latest Business Outlook Survey by the BoC shows hiring intentions are positive, yet below their long-term average.

With hiring remaining anemic and population growth to ease only slowly, the unemployment rate is expected to continue to increase in early 2025 and peak at around 7%. However, the sharp slowdown in the labour force stemming from the new immigration targets points to a weakening in the supply of labour. At the same time, demand is expected to remain marginally positive, meaning that we should expect the unemployment rate to stabilize and drift lower around mid-2025, reaching about xx% by the end of the year.

However, with major downside risks potentially affecting the economy in 2025, potentially leading to a recession, the potential for layoffs cannot be ruled out. The decline in income associated with job losses could have significant ripple effects on the rest of the economy and lead to some financial stability concerns. (see Will it be a hard landing or a soft landing? The labour market will decide)

Inflation

Inflation is currently at the mid-point of the BoC’s inflation target and is expected to remain under control over the projected period. Nevertheless, a base effect is expected to lead to a rise in inflation in late 2024 and early 2025, reaching about 2.5% by February 2025, before moderating to slightly below 1.5% by mid-year. The BoC’s preferred measures of core inflation, CPI-Trim and CPI-Median, will take longer to reach 2%. We expect the average of both core measures to reach 2% in early 2025.

While inflation is back within target, some components are expected to remain elevated. As such, the shelter component is likely to remain high for some time despite a deceleration in rent increases and the impact of lower interest rates on mortgage interest rate payments. Similarly, food prices are slightly stickier than expected, likely due to the impact of a weaker Canadian dollar on the cost of imported food, especially fresh food. Nevertheless, continued excess supply in the Canadian economy in late 2024 and early 2025 should hold back domestic inflationary pressures.

The main concern for the BoC is that elevated shelter and food inflation costs could keep inflation expectations elevated, slowing their return to levels more consistent with the inflation target. It is interesting to note that consumers’ perceived inflation remains elevated and well above observed inflation.

The Canadian dollar

The Canadian dollar has depreciated significantly since September, losing about 4.8%, reaching a bit more than 1.40 against the U.S. dollar. It is important to note that, while most of the depreciation is due to a widening in the rates differential, it was mainly due to a rise in U.S. rates rather than a decline in Canadian ones. As such, we note that the value of the Canadian dollar versus other major currencies has been much more stable, with CAD appreciating by 1% against EUR and JPY over the same period.

As mentioned previously, while the Bank of Canada is expected to cut its policy rate more than the Federal Reserve, this divergence in monetary policy is already most priced in the value of the Canadian dollar. Nevertheless, we expect the extent of any further depreciation to be limited and expect the Canadian dollar to reach about 1.45 by mid-2025, before stabilizing and appreciating somewhat afterwards.

However, a negative shock to the Canadian economy, such as the proposed import tariffs or a further slowdown in the Canadian economy, could lead to further depreciation. Similarly, greater resilience of the U.S. economy could lead to a further appreciation of the USD.

Alberta’s economy

Alberta’s economy grew by 2.3% in 2023 and was amongst the fastest-growing provinces. The details show that most of the growth came from net exports, household spending, and government spending, while a decline in inventories, business investment, and residential investment hindered growth. The increase in net exports was mainly the result of strong exports (contributing 1.9pp), while a decline in imports added to growth (+0.1pp).

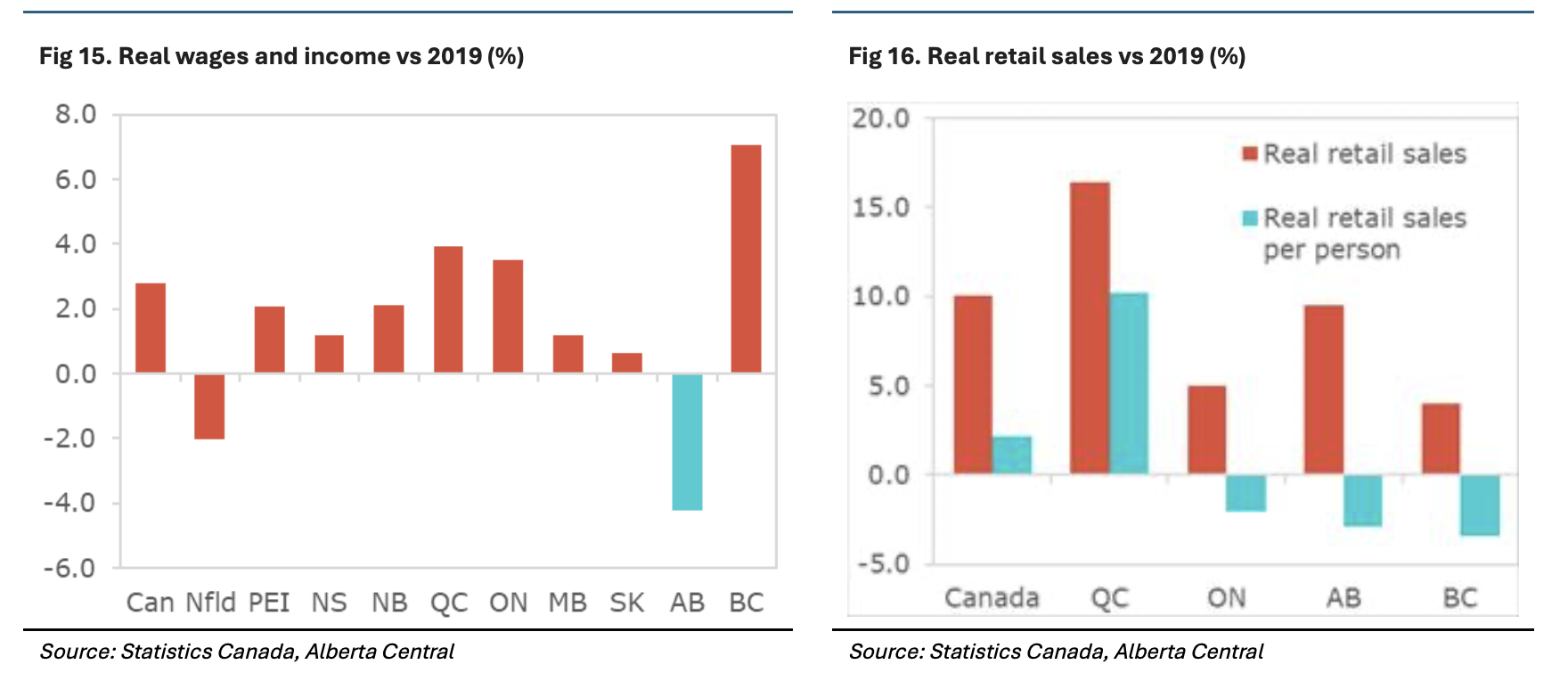

While growth was strong in Alberta, the province is also experiencing a “me-cession”. However, the difference is that it is more acute in the province than elsewhere in Canada; Alberta is exhibiting a more extreme situation where spending per person has declined more than in the rest of the country, while the more substantial increase in population has meant that it is one of the fastest-growing provinces in Canada.

Consumer spending

The most recent provincial accounts show that consumer spending in Alberta is 8.4% higher than in 2019, mainly due to strong population growth. As such, on a per capita basis, consumer spending is 2.4% below that of 2019 in Alberta, compared to -0.1% for the country as a whole. If we were to assume that population growth would have remained at its pre-pandemic trend, we estimate that growth in Alberta would have been a full percentage point lower at 1.3% in 2023 and still have been one of the fastest-growing provinces. Using the latest retail sales data, we estimate that this trend will continue in 2024 and that a large proportion of Alberta’s growth this year is due to record population growth.

The two major factors explaining the underperformance in spending per person in Alberta relative to the rest of the country are:

- Real wages and income have underperformed significantly compared to other provinces in recent years. As such, we calculate that real wages and income per person in Alberta are currently about 4% below their 2019 levels. Comparatively, the same measure for the rest of the country has increased by almost 3% over the same period (see Where’s the boom? And the rise and fall of the Alberta Advantage, for an explanation of the underperformance). As a result, Albertans’ purchasing power is lower now than pre-pandemic, forcing households to adjust their spending accordingly.

- Albertans are amongst the most indebted households in Canada, with a debt-to-income ratio estimated at 179%; the most indebted households are in Ontario (with 210%) and BC (with 225%). While the higher proportion of non-mortgage debt in Alberta than in Ontario and BC means that a greater proportion of household debt in the province is at a fixed rate, the impact of higher interest rates on the debt-service ratio is still high.

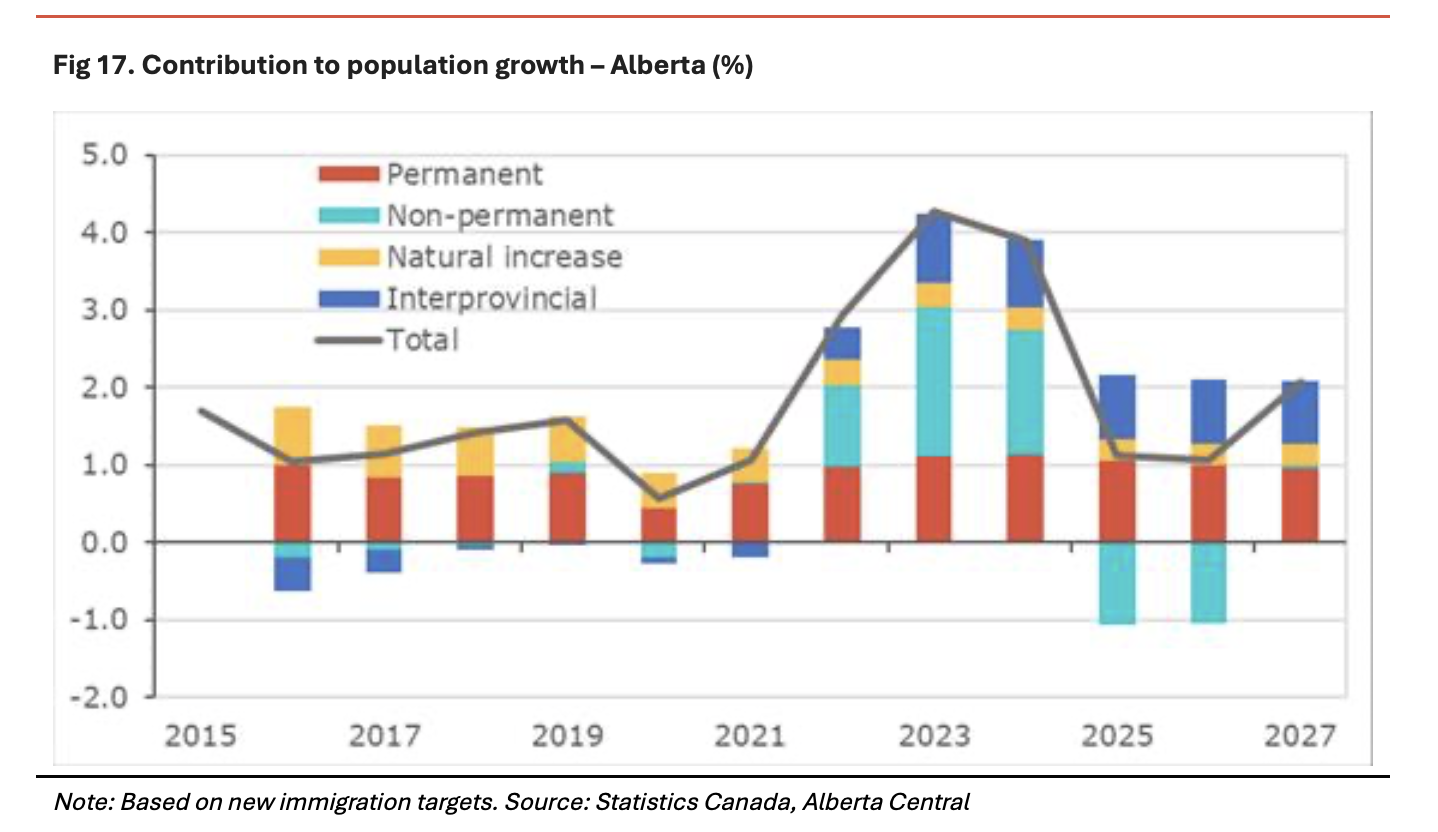

With that, we note that a greater share of consumers in Alberta are struggling financially. As such, the consumer insolvency rate is amongst the highest in Canada and at a record high. This will likely constrain consumer spending in the near term to an extent.

Population growth

The change in the federal government’s immigration target will also slow Alberta’s population growth. If we assume that the reduction in immigration affects provinces proportionally to the impact of immigration on population growth in recent years, with both the natural increase in population and interprovincial migration remaining unchanged, we estimate that Alberta’s population will slow to about 1.1% in 2025 and 2026, from the current 4.3%. Such a deceleration will lead to a significant growth slowdown in 2025 and 2026, especially via aggregate consumer spending.

However, we would note some uncertainty regarding the strength of population growth. As such, it is unclear whether interprovincial migration will continue at the same pace in the coming years. There is a risk that it could be weaker, especially if lower rents and downward pressures on house prices lead to some improvement in affordability in other provinces, thereby making a move to Alberta slightly less appealing.

Housing

The Albertan housing market has continued to outperform the rest of the country in 2024 thanks to strong population growth, with transaction levels more than 50% above compared to pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, while prices have stagnated in most regions, house prices are rising in the province, especially in metropolitan areas. Strong population growth and higher affordability explain this outperformance.

However, slower population growth next year could reverse this trend. A reduction in non-permanent residents and new supply entering the market will likely constrain rent. By extension, this situation could spill over to the condo segment of the housing market. Nevertheless, lower interest rates and continued housing affordability in Alberta should continue to support the single-family segment of the market. Similarly, despite a slower housing market, investment in new supply is likely to remain robust.

Labour market

Although job creation was robust in Alberta in 2024, it was not enough to absorb all newcomers into Alberta’s labour force. As a result, the unemployment rate has been trending higher, reaching 7.5 % in October, higher than in the rest of the country. While population growth is expected to slow, it will remain positive and higher than in the rest of the country, meaning that labour supply will continue to rise. This means that the unemployment rate risks declining more slowly in the province unless labour demand, i.e. hiring, remains stronger than in the rest of the country. Nevertheless, we expected the unemployment rate to peak at about 7.5% in early 2025 before easing and ending the year at around 6.3% by the end of 2025.

External sector

Exports were a significant source of growth in 2023 and 2024. As such, the opening of the TMX pipeline in May 2024 has allowed for an increase in oil exports and some long-needed market diversification. We also note that the TMS is helping Alberta’s oil producers receive better prices for their products, with the spread between the Western Canada Select (WCS) and the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) not widening in recent months, contrary to its usual seasonal patterns.

Barring any negative impact from potential U.S. import tariffs, we anticipate that exports will remain an important contributor to growth in 2025. The main drivers will be the completion of the LNG Canada export terminal and the continued increase in oil exports thanks to the TMX pipeline.

Business investment

Nonresidential investment eased slightly in 2023, declining by 5.2%; this was driven by both a lower investment in machinery and equipment and nonresidential structures. We expect a modest increase in private investment in 2024, supported by nonresidential investment and investment to increase oil production.

Supported by the extra export capacity provided by the opening of the TMX and Coastal Gaslink pipelines, investment in the oil and gas industry is expected to continue to increase in 2025. As such, the Canadian Association of Energy Contractors expects drilling activity to reach its highest level since 2015, with an expected 7.3% increase in activities in 2025. However, even with this increase, the level of investment in the oil and gas sector remains almost 40% below its peak of 2014.

However, the uncertainty created by the U.S. import tariffs and concerns regarding the impact of weaker demographics on the economy could hold back some investment, while lower interest rates could provide support.

Risks

There are many risks to Alberta’s outlook for 2025. On the downside, U.S. import tariffs could prove very disruptive to Alberta’s economy, especially if there is no carve out for Alberta’s oil exports. It is estimated that Alberta’s exports to the U.S. represent about a third of its GDP, while about 13% of jobs in the province would be impacted by tariffs. These make Alberta’s economy the most vulnerable to U.S. tariffs. Similarly, with downside risks to growth in China, global oil consumption could be weaker than expected at a time when the U.S. could be boosting production. Such a scenario could lead to a decline in oil prices, causing a drag on the Alberta economy and the province’s finances. On the upside, there is a risk that the reduction in immigration targets may not be fully implemented, meaning that Alberta’s population could grow more than expected. This would support economic activity in the form of higher aggregate consumer spending.

Looking for more ? Subscribe now to receive Economic updates right to your inbox here!

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication