Economic insight provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Main takeaways

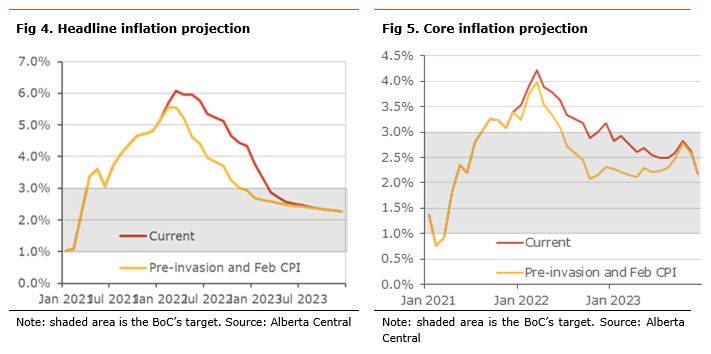

- The sharp rise in global commodity prices, especially oil and food, will push inflation higher in the coming months. In addition, stronger inflation in February is raising the starting point for inflation projections. As such, projections for inflation are higher than previously thought this year with headline inflation 1 percentage point higher and 0.5 percentage points for core inflation.

- We now expect the BoC to hike its policy rate by 25bp at every meeting this year, bringing the policy rate to 2.00% by the end of the year. Moreover, we think the BoC may decide to front-load some of the hike, by increasing its policy rate by 50bp at one of the meetings. We would not be surprised with such an outcome at the April meeting.

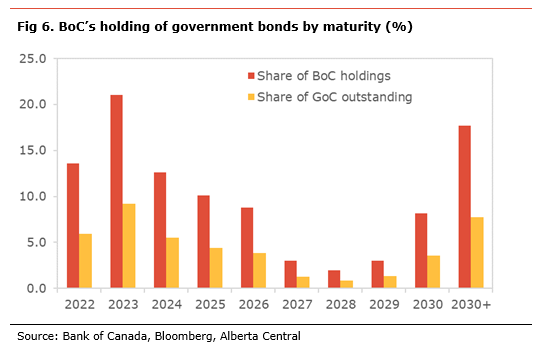

- We also believe the BoC will initiate quantitative tightening (QT) in the coming months by no longer reinvesting maturing bonds. The BoC has about $60bn and $90bn in bonds maturing this year and the next, respectively; this is, roughly 15% of Canadian government bonds in circulation. Such removal of liquidity will have an impact on rates along the yield curve and could substitute the need for hikes in the policy rate.

- The amount of rate hikes, especially later this year and the next year, is likely to depend on the magnitude of QT, the impact of the global monetary tightening, and the impact of higher interest rates on heavily indebted households.

- Nevertheless, the BoC needs to slow the domestic economy and create excess capacity, i.e. a negative output gap, to offset inflationary pressures generated by the rise in global commodity prices and inflation expectations.

- The risk is that it could stall economic activity or even lead to a recession. The recessions of the early 1980s and 1990s both had their origins in monetary tightening to lower inflation.

- Already, households are facing important headwinds with inflation reducing their purchasing power, interest rates rising their debt-service ratio and real disposable income declining as government support programs are wound down.

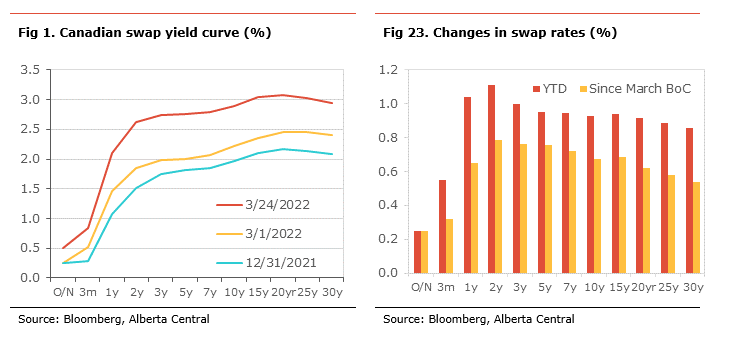

Market interest rates have increased significantly since the beginning of the year and, more specifically, since the start of March, following the Bank of Canada’s decision to increase its policy rate by 25bp and the surge in commodity prices following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The increase in interest rates has been broad-based but more abrupt in the front-end of the yield curve, especially in the 1-to-2-year maturity segment of the curve. The change in 2-year yields has been quite significant, increasing by about 110bp since the start of the year and 65bp since the March BoC meeting. The level of 2-year yields is currently 2.63%. If we exclude a brief period in 2018, when it was marginally higher, the current level is closer to its highest since the global financial crisis in 2008.

Why did rates increase so much?

The main factor pushing interest rates higher is increased expectations that the BoC will need to be more aggressive in increasing interest rates to fight inflation. Looking at the overnight Index Swap curve (OIS), the implied policy rate for the end of 2022 is 2.42%, indicating an expectation of almost 200bp in hikes before the end of the year. Expectations have increased by about 55bp since the March BoC meeting.

Similarly, using Bankers Acceptances (BA), the market is currently expecting the BoC to increase interest rates by 150bp by the end of 2022. Expectations have increased by 75bp since the March BoC meeting.

Inflationary pressures are increasing

In recent weeks, there has been further indication that inflation will be higher than previously expected, in a context where inflation is already well above the BoC’s target.

The release of the February CPI showed that inflation was higher than expected at 5.7% vs. expectations of 5.5%. This creates a higher starting point for inflation for the projection. (See here for the comment on the latest inflation release).

In addition, as a result of the war in Ukraine, we have seen global commodity prices rise sharply. The conflict between Russia and Ukraine risks creating huge supply constraints on food prices, especially wheat and other cereals, and energy, mainly oil and gas. (See here for some thoughts regarding the impact of the conflict on Canada and Alberta).

Oil prices (WTI) have increased sharply since the start of the conflict, from $92 a barrel to about $110 currently, reaching a high of $130 at one point. This has been passed onto consumers via higher gasoline prices and will contribute to pushing inflation higher in March. Some leading analysts are predicting that oil prices could reach $200 at some point this year. Similarly, we are seeing a big increase in agricultural prices. However, the pass-through to consumers and to inflation will be more gradual. Our analysis suggests that the rise in agricultural prices will have an inflationary impact in the next 12 months.

The surge in commodity prices and the higher starting point are pushing higher the expected level of inflation for this year. Headline inflation is expected to reach 6.1% in March and remain close to 6% until the summer, a full percentage point higher than previously thought, before gradually easing. The impact on core inflation is a bit more subdued because of the exclusion of some of the impacts of higher energy prices. Nevertheless, the measure includes the spillover higher energy cost will have on other prices. Core inflation is expected to reach 4.2% in March before returning below 3% in the Fall. Over most of 2022, core inflation is expected to be 0.5pp higher than previously estimated.

What will the BoC do?

A stagflationary environment, where we see rising inflation while there are some strong headwinds on growth coming from high energy prices, will be a major headache for the Bank of Canada. In such a situation, the Bank of Canada should normally look through the first-round impact of higher global commodity prices on inflation through higher gasoline prices and food prices and focus almost exclusively on domestically generated inflation.

However, it needs to prevent and react to any increases in inflation expectations that would lead to higher wage growth and more broad-based price increases as businesses pass extra costs onto consumers. In other words, the central bank needs to prevent the higher inflation rate from becoming entrenched and permanent.

Inflation is already running well above target at close to 6%. With additional inflationary pressures, inflation expectations are likely to rise further. This will require an additional reduction in the amount of policy accommodation. So, the BoC needs to raise interest rates more aggressively than expected.

Policy rate

As we have explained in the past (see here), central banks have little tools to fight supply-induced inflation. Increasing interest rates will not lower the price of oil, gasoline and food, make the global chip shortage disappear, unclog transportation hubs, or lower transportation costs. It leads to a difficult balance of fighting inflation without jeopardizing the recovery or pushing the economy into a recession.

In other words, the BoC needs to slow domestic demand to reduce domestic inflationary pressures enough to offset inflationary pressures generated by the rise in global commodity prices and inflation expectations. Concretely, it means the central bank needs to increase rates enough to bring growth below the potential and generate a negative output gap to reduce inflationary pressures. The risk is that it could stall economic activity or even lead to a recession. The recessions of the early 1980s and 1990s both had their origins in monetary tightening to lower inflation.

With this in mind, we expect the BoC to increase its policy rate by 25bp at every remaining meeting this year, ending the year at 2.00%. However, with inflation running faster than expected, there is a risk the BoC could front-load some of the tightening by increasing rates by 50bp to get ahead of the curve. We believe that the probability of a 50bp hike is high for the April meeting.

Quantitative tightening

The speed and magnitude of rate hikes will depend on quantitative tightening (QT), i.e. how quickly the BoC will reduce its holdings of government bonds. The BoC currently holds about $430bn in bonds, about $421bn in Government of Canada bonds (GoC), representing about 44% of the GoCs in circulation, and $9bn in Canada mortgage bonds.

We believe the BoC could start QT as early as April by no longer reinvesting maturating bonds. There are $58.6bn in bonds maturing this year in the BoC’s holdings, representing almost half of all GoC bonds maturing this year (6% of all GoC bonds outstanding). The BoC also holds $90bn of bonds maturing in 2023 (21% of its holdings), about half of the bonds maturing next year (9% of all GoC bonds outstanding) (see Fig 7). Having so much liquidity withdrawn from the market will push bond yields higher.

This reduction in the BoC’s balance sheet could be a substitute for some of the hikes in the policy rate that are currently priced in by financial markets. The exact impact of QT is not very well understood and quantifiable, even for the BoC, adding uncertainty to the outlook for the policy rate, especially for the second half of this year and in 2023.

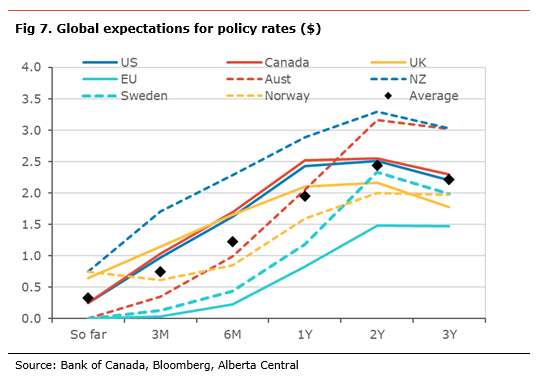

Global monetary tightening

Another aspect that often seems lost is that every major central bank in the world is also expected to tighten their monetary policy this year (see Fig 8). Taken individually, those actions remain relatively small. However, it is not clear what impact such a coordinated global tightening of monetary policy will have on the global economy, especially at a time where higher commodity prices, especially energy, will slow growth. Canada as a big exporter may be more affected by a global slowdown than others.

Is there a role for governments in fighting inflation?

Some have argued that the government, federal or provincial, needs to address the rising living costs generated by higher energy and food prices. Already, the government of Alberta announced it would forgo its provincial tax revenue on gasoline. While the idea of supporting household purchasing power is appealing, it has some important drawbacks:

- Reducing taxes to lower prices would increase the fiscal deficit and government debt in most provinces and at the federal level, as it would cut fiscal revenues. Someone has to pay the higher price, either consumers or the government. Alberta is in a different situation, as the revenues lost from a cut in the gasoline tax are likely more than offset by the increase in bitumen royalties resulting from surging oil prices.

- Cutting taxes to compensate for price increases would only have a one-off impact on inflation, changing the level of prices, not the pace of the rise. Moreover, it would support domestic demand leading to increased inflationary pressures, all else equal. As a result, the BoC may need to increase interest rates more than otherwise would be the case to offset these new inflationary pressures.

Downside risks to the horizon

The sharp rise in energy and food prices will have a negative impact on both global and Canadian growth. As such, a sharp increase in energy prices have been often associated with a stalled global economy, as most major countries are net importers of energy. This is because a sharp reduction in purchasing power means less spending on other items.

In Canada, consumers are set to face some strong headwinds over the next year. These include:

- The high level of inflation, while wage growth remains contained, suggests that a household’s purchasing power was already being eroded by the general increase in prices. The accelerations in inflation will only worsen the situation.

- In response to increasing inflationary pressures, the Bank of Canada started raising interest rates at its March meeting and further increases are expected. With Canadian households being heavily indebted, each increase in interest rates will increase the debt-service ratio.

- Household disposable income, after increasing above the trend during the pandemic thanks to the various government programs, is normalizing. As such, the most recent data for the fourth quarter of 2021 shows that disposable income declined by 1.3% q-o-q (2.5% in real term).

All of these factors are pointing to headwinds for consumer spending. Households will need to dedicate a greater share of their income towards necessary expenses (food, shelter, transportation, debt-services) at the expense of discretionary spending (eating out, travel, etc.).

Households in Canada have never been as indebted as they are currently, with debt-to-disposable income reaching 186%. Despite the record level of debt, the debt-service ratio remains low thanks to historically low interest rates. However, as interest rates go up, obligated debt repayment (principal and interest) will increase, taking a gradually bigger bite out of household’s budget, thereby necessitating a reduction in discretionary spending.

We estimate that Canadian households have accumulated about $320bn in savings during the pandemic. Some of this amount has been used to repay some debt, mainly credit card debt, and to invest. Nevertheless, we estimate Canadian households have accumulated about $185bn in demand deposits. Whether households use the savings accumulated during the pandemic to maintain their level of spending or keep it as precautionary spending will matter greatly for the outlook.

The housing market is also likely to be affected. As we have shown recently (see here), declining affordability due to increasing interest rates is likely to slow the resale market. Moreover, a reduction in purchasing power may force some households to reconsider their housing needs, i.e. purchase smaller, or less expensive houses, or continue renting. The high transportation cost could also reduce the attraction of living further away from urban centers.

Conclusion

Higher inflation and rising inflationary pressures will require the BoC to be more aggressive in raising its policy rate. However, the amount of rate hikes, especially late this year and next year, is likely to depend on the magnitude of QT, the impact of the globally coordinated monetary tightening, and the impact of higher interest rates on heavily indebted households.

There is a risk that, by increasing rates to fight inflation, the BoC could cause a recession. The need to generate a negative output gap to reduce inflationary pressure could push the economy into contraction. After all, the recession of the early 1980s and 1990s were both caused by a tightening in monetary conditions in an effort to bring inflation lower.

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.

Alberta Central member credit unions can download a copy of this report in the Members Area here.