Economic insight provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Bottom line

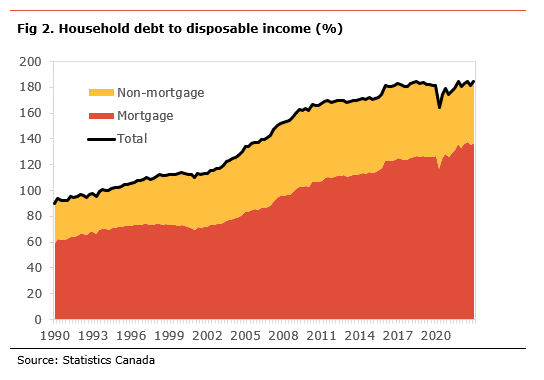

Household indebtedness has been a significant concern and risk for the Canadian economy for some years. After a sizeable improvement during the pandemic, households’ debt-to-disposable income ratio is close to its highest levels on record at 184.5%. A continued increase in debt levels and a normalization in disposable income, as government transfers return to their pre-pandemic levels, explain the rise in indebtedness.

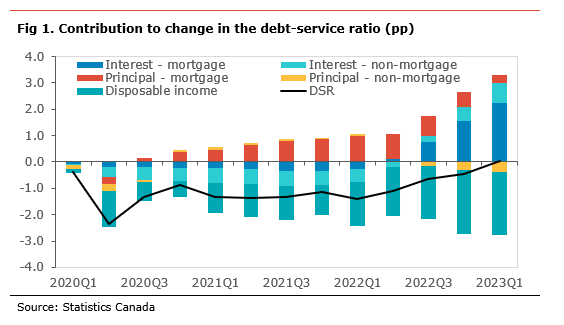

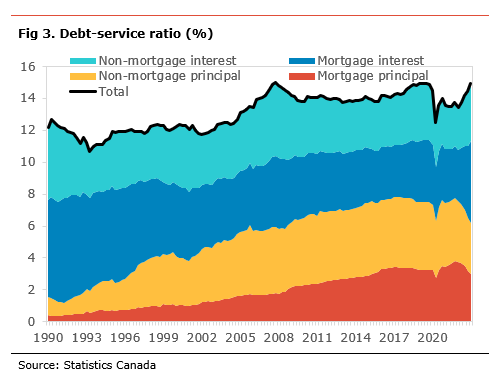

As a result of the increase in interest rates over the past year, the debt-service ratio rose to 14.9% from 14.4% in the first quarter of 2023. Interestingly, despite a continued increase in the level of debt, obligated principal payments continued decreased on the quarter. This is likely the result of a smaller share of payments going to the principal in the case of borrowing at variable rates but with fixed periodic payments and to some borrowers extending the amortization period of their debt to offset the increase in interest rates.

With indebtedness close to a record high and the Bank of Canada having increased interest rates sharply, 450bp since the beginning of 2022, there are some concerns regarding the impact of those interest rate increases on households’ ability to service their debt. We are already witnessing a sharp rise in the debt-service ratio and further increases are likely as more borrowing gets renewed at higher interest rates.

As mentioned, households are already reducing their principal payments to offset the pressures from higher interest payments, easing the negative impact on their budget. This is evidenced in the sharp rise in proposals (renegotiation of terms) in the insolvency data. flexibility is likely to help contain defaults for now. However, a big risk is that the situation could become unsustainable if the upcoming recession proves deeper than expected, leading to significant job losses.

Households have accumulated significant savings during the pandemic, about $400bn, potentially providing some buffer. The pace of accumulation is slowing and there is little size yet of significant saving withdrawals. This situation provides a cushion for households to absorb the interest rate shock. However, as mentioned previously, this could change rapidly if we were to see significant jobs loses.

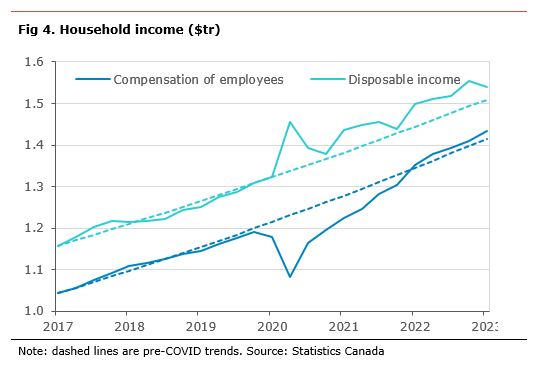

The ratio of household debt to disposable income rose in the first quarter of 2023, increasing to 184.5%. This is only 0.1 percentage point below the record sert in 2018Q3. This means that households owe on average $1.85 in debt for each dollar earned. The deterioration in the ratio, rising by 2.8 percentage points (pp), was the result of a decline in disposable income (-1.0% q-o-q), while debt increased a more modest (0.6% q-o-q).

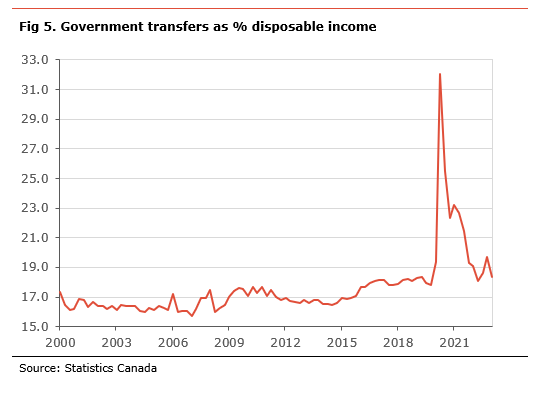

The decline in disposable income resulted from a decrease in government transfers (7.7% q-o-q), while the compensation of employees increased 1.8% q-o-q. The share of government transfer in disposable income declines to 18.4% from 17.7%, still slightly above its pre-Covid levels.

On the debt side, the increase in total household debt was due to a rise in both mortgage debt (+0.5% q-o-q) and non-mortgage debt (+0.6% q-o-q), mainly from consumer debt.

Since the start of the pandemic, household debt to disposable income has decreased by 3.4pp. We estimate that if it were not for the continued rise in disposable income, the indebtedness ratio would stand at 217.2%. Conversely, if households didn’t accumulate debt over the period, the ratio would be 159.9%.

The debt-service ratio, the share of income households need to spend to repay the interest and obligated principal payment on their debt, increased to 14.9% from 14.4%. This means that, for each dollar earned, households need to spend $0.15 to service their debt. The increase resulted mainly from the lower disposable income.

The details show that the rise in debt payments resulted from an increase in the interest payments (+5.3% q-o-q) as interest rates over the past year continued to pass-through higher interest debt payments. Despite an increase in debt levels, obligated principal payments declined on the quarter (-2.0% q-o-q). This is likely the result of a greater share of fixed debt payment on variable rate debt having to be redirected away from principal payment to cover the increase in interest payments.

The debt-service ratio is back to where it was at the start of the pandemic. However, it composition has changed. As such, the contribution from debt payments is higher by 1.6pp, with most of the increase coming from higher interest payments (contributing +1.0pp). Since the Bank of Canada started to increase interest rates, debt payments have increased by 1.9pp. With more rate increases in the first quarter of 2023 and borrowers renewing at higher rates, we should expect further rises in interest payments. Moreover, most of the increase is coming from mortgage debt payments (+1.6pp), while it’s almost flat for non-mortgage (+0.1pp). The continued growth in disposable income helped hold back the debt-services ratio, contribution -2.0pp.

The household saving rate declined to 2.9% from 5.1%. The lower saving rate was due to a decline in income, while consumer spending were robust on the quarter. According to the national balance sheet data, households have accumulated about $400bn in saving since the start of the pandemic. However, the pace of accumulation is slowing. Of this amount, about $290bn is held in bank deposits, and about $165bn has been invested in equity and investment funds.

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.