Economic insight provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Bottom line

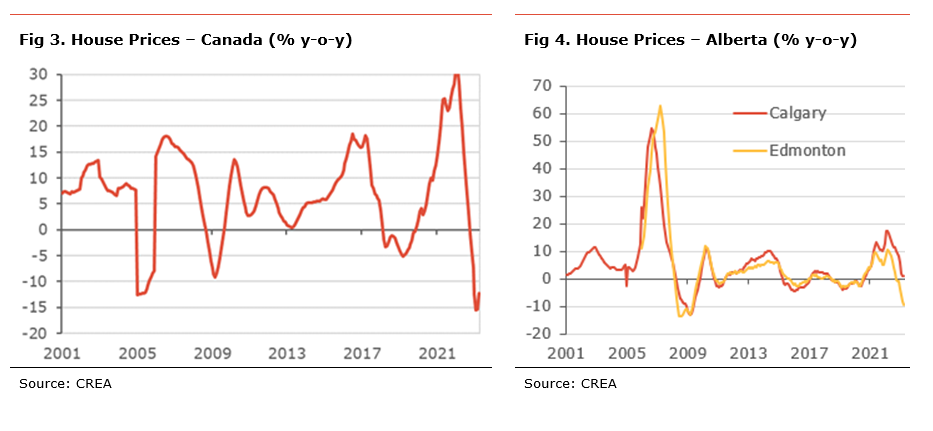

National house prices increased again April. Since the start of the correction, prices nationally have fallen by 14.0%. The correction has been more significant in some markets, especially those with the most significant post-pandemic gains. However, the continued decline in inventories, while demand is improving, is beginning to impact the housing market. The continued decline in inventories is likely to constrain activity and provide support to house prices, despite the cooling impact of higher interest rates.

In Alberta, housing market activity remained robust by historical standards. However, we note a continued divergence between the metropolitan areas. Prices in Calgary have continued to increase over the past year and the city remains one of the strongest cities in Canada, supported by low inventories and the weakest new listings since 2002. On the flip side, the price correction continued in Edmonton, as inventories remained higher. With less froth accumulated during the pandemic, Alberta’s market is less prone to a sharp correction than other regions. In addition, strong migration to Alberta also supports activity and prices compared to elsewhere in the country.

Low interest rates have been one of the main drivers of the housing market, supporting affordability. Despite affordability being at its lowest in decades in many cities (see), housing demand is picking up, supported by the strong labour market, potential buyers resetting their expectations of what they can afford and a fear of missing out. The continued lack of supply in many regions and increased immigration will likely continue to support house prices and prevent further correction, with the health of the labour market likely the key to the outlook for the housing market.

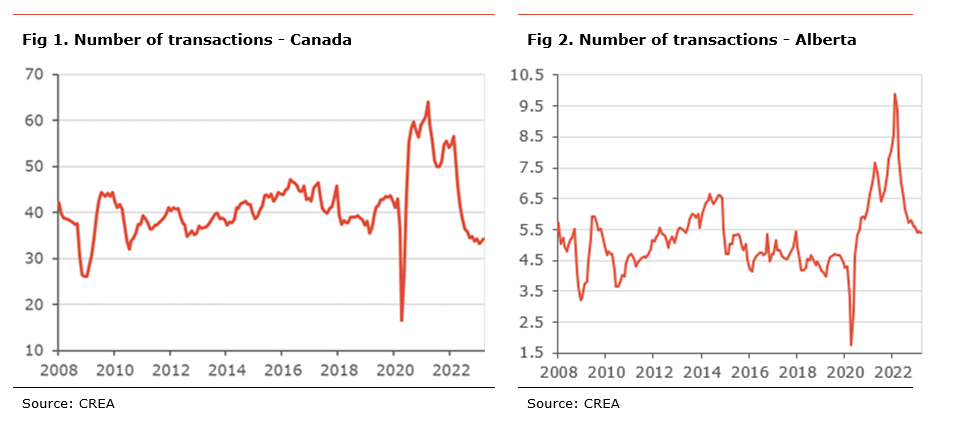

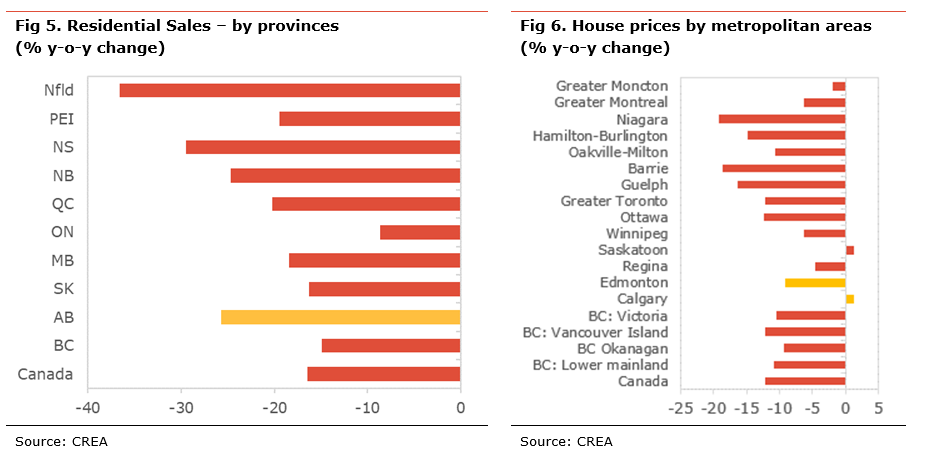

Activity in the Canadian housing market increased by 11.3% m-o-m seasonally-adjusted in April. This is the biggest monthly increase since the boom during the pandemic. Nevertheless, the number of transactions, at 38.2k, is 7% lower than on average in 2019 and 16% lower than for the same month last year. It is important to note that all the year-on-year comparisons are distorted by the sharp boom in activity a year ago and, as a result, we will focus on the changes compared to 2019. Activity was higher in most provinces, led by BC, Ontario, and Albert, while it declined in New Brunswick and Newfoundland. In Alberta, the number of transactions rose (+7.8% m-o-m) in April, but activity was almost 20% higher than in 2019.

There continue to be some divergences between provincial markets. Compared to the average level of 2019, the number of transactions is well above its pre-pandemic level in Alberta (+31%), Saskatchewan (+19%), and Newfoundland (+8%). On the flip side, activity is well below in Quebec (-25%), Nova Scotia (-18%), and Ontario (-13%)

New listings rose 1.6% m-o-m seasonally-adjusted in April, after two consecutive months of decline. New listings were mixed at the provincial level, with the biggest gains in Quebec, BC, Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Manito. On the flip side, new listings declined in New Brunswick, Alberta, Nova Scotia, and PEI.

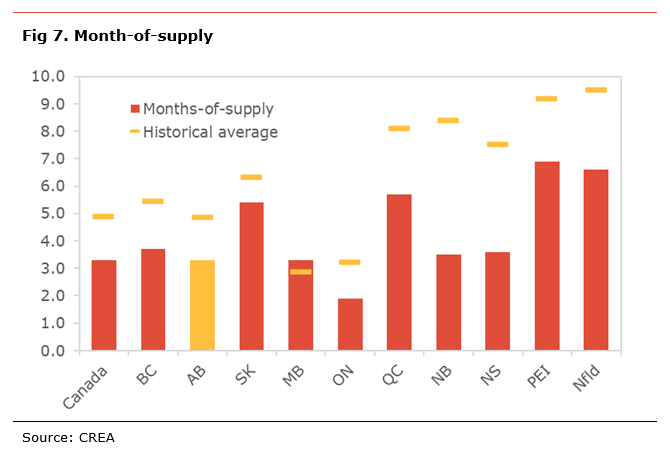

With sales activity stronger than new listings in most regions, the month-of-supply measure[1] inched lower to 3.3 nationally, about 1.6 months higher than its recent low. Based on this measure, most provinces have seen a decline in inventories in March, with the exception of Quebec and Newfoundland. Also, inventories level are still below their 2019 levels in all provinces.

Compared to the lowest level of inventory over the past two years, the month-of-supply has increased the most in PEI (+4.6 months), Quebec (+3.5 months), BC (+1.9 months), and Nova Scotia (+1.9 months). It has increased the least in Ontario (+1.9 months), Alberta (+1.3 months), and Saskatchewan (+1.3 months). With a month-of-supply at 3.3, Alberta’s housing market is at its tightest since 2007, if we exclude the pandemic.

With a rebound in sales and a continued decline inventories, the MLS House Price Index rose by 1.6% m-o-m, the most since February 2022. Compared to last year, house prices eased nationally by 12.3% y-o-y. Many areas saw higher prices in April. The biggest monthly increases were in Hamilton-Burlington (+5.4% m-o-m), Oakville-Milton (+4.7% m-o-m), Okanagan (+3.0% m-o-m), Guelph (+2.6% m-o-m), Toronto (+2.4% m-o-m). Prices declined only in Vancouver Island (-0.9% m-o-m), Saskatoon (-0.5% m-o-m), and Edmonton (-0.4% m-o-m).

On a y-o-y basis, almost all regions have seen lower prices, with the most significant declines in Niagara (-19% y-o-y), Barrie (-19% y-o-y), Guelph (-16% y-o-y), and Hamilton-Burlington (-15% y-o-y). However, prices are higher compared to last year in Saskatoon (+1.3% y-o-y) and Calgary (+1.2% m-o-m).

Compared to their recent peaks, prices have declined by 14.0% nationally. However, prices are still almost 33% higher than they were in January 2020 on the eve of the pandemic. Compared to their recent peak, prices dropped the most in Niagara (-21%), Barrie (-20%), Guelph (-19%), Hamilton-Burlington (-18%), and Oakville-Milton (-18%). Prices have corrected the least in Saskatoon (-1.4%), Moncton (-3.7%), Regina (-4.5%), and Montreal (6.8%). Prices have not declined in Calgary.

In Alberta, benchmark prices rose 1.0% m-o-m and are up 1.2% y-o-y in Calgary and decreased 0.4% m-o-m and -9.2% y-o-y in Edmonton. There continues to be a divergence between the performance in Edmonton and Calgary, likely resulting from continued higher inventories in Edmonton.

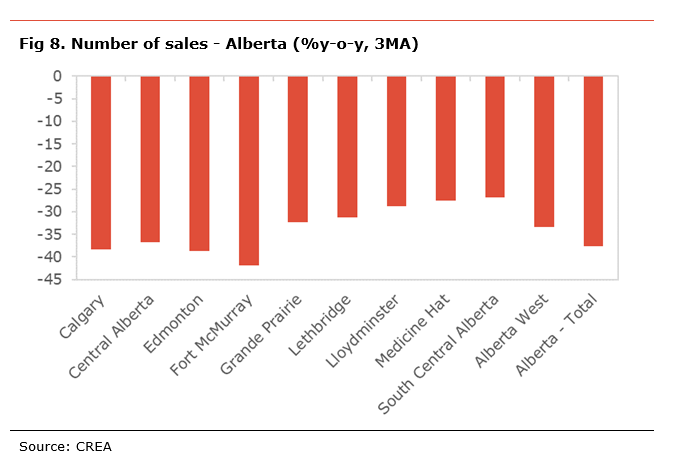

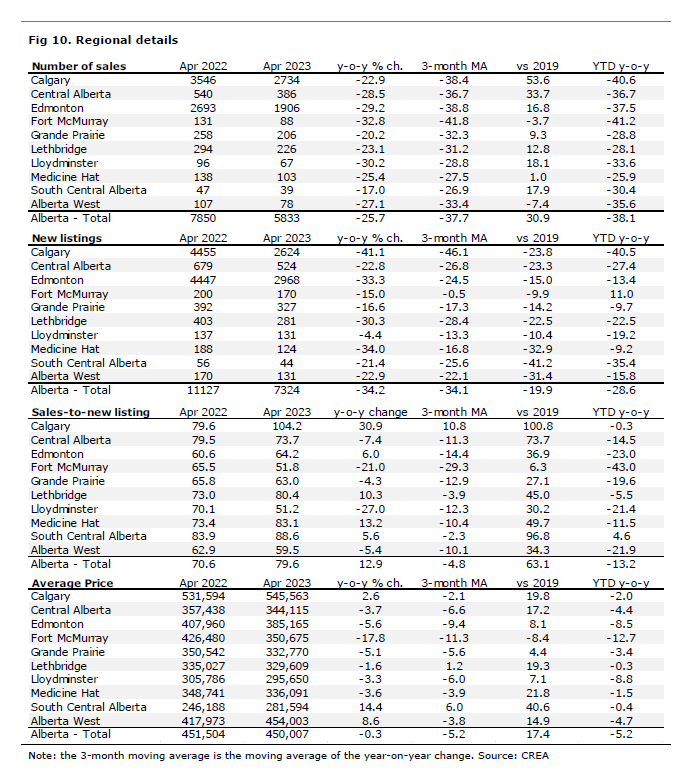

In Alberta, the housing market remains robust, with transactions still well above their pre-pandemic level. However, the number of transactions has eased in all regions compared to last year’s same month. (see table below for details). Compared to the average level of transactions in 2019, activity in the province increased by 31%, led by Calgary (+54%), Central Alberta (+34%), Lloydminster (+18%), South Central Alberta (+18%), and Edmonton (+17%).

New listings declined on the month at the provincial level. Compared to the average level of new listings in 2019, new supply in the province decreased by 19.9% and was lower in all regions. New listings declined the most compared to 2019 in South Central Alberta (-41%), Medicine Hat (-33%), Alberta West (-31%), Calgary (-24%), Central Alberta (-23%), and Lethbridge (-23%).

With sales stronger than new listings in recent months, many regions have seen a tightening of their housing markets. However, conditions are tightening in Calgary and South Central Alberta. The primary seller’s markets are Calgary, South Central Alberta, Lethbridge, and Medicine Hat. The main buyer’s markets are Fort McMurray, Grande Prairie, Lloydminster and Alberta West.

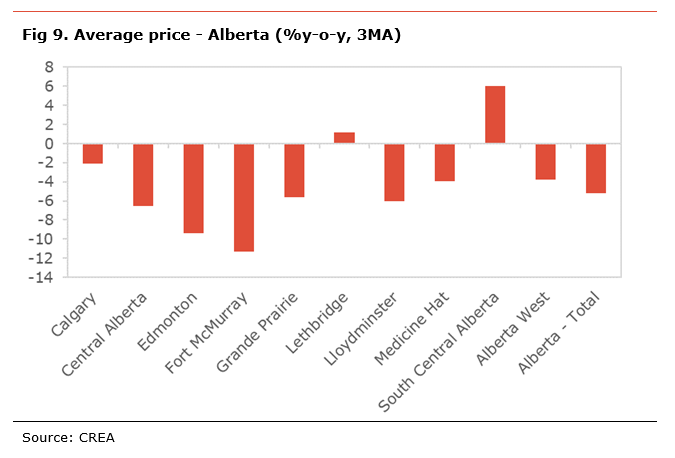

Average house prices have been almost stable (-0.3% y-o-y) on a 3-month moving average of the year-on-year in the province, with lower prices in most regions. The biggest house price declines were in Fort McMurray (-11.3%), Edmonton (-9.4%), Central Alberta (-7%), Lloydminster (-6%), and Grande Prairie (-6%). Prices increased in South Central Alberta (+6%) and Lethbridge (+1.2%).

In Lethbridge (+0.1%) and declined the least in Medicine Hat (-0.4%), Grande Prairie (-2.5%), and Calgary (-3.5%). The biggest house price declines were in Lloydminster (-11.0%), Fort McMurray (-10.3%), Edmonton (-9.8%), and Alberta West (-8.7%).

[1] The month of supply measures how many months is would take at current sales volume and without an increase in listings to bring inventories to 0.

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.