Economic insight provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud

Main takeaways

- House prices have continued to increase sharply over the past year. This raises concerns regarding whether the housing market could be in a bubble and what will happen when the Bank of Canada (BoC) raises interest rates.

- We’ve updated our valuation and affordability metrics for Canada’s main cities: Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal (see here for the original report).

- One of the main findings is that the current record low interest rate environment remains a powerful force keeping affordability high, despite continued increases in house prices.

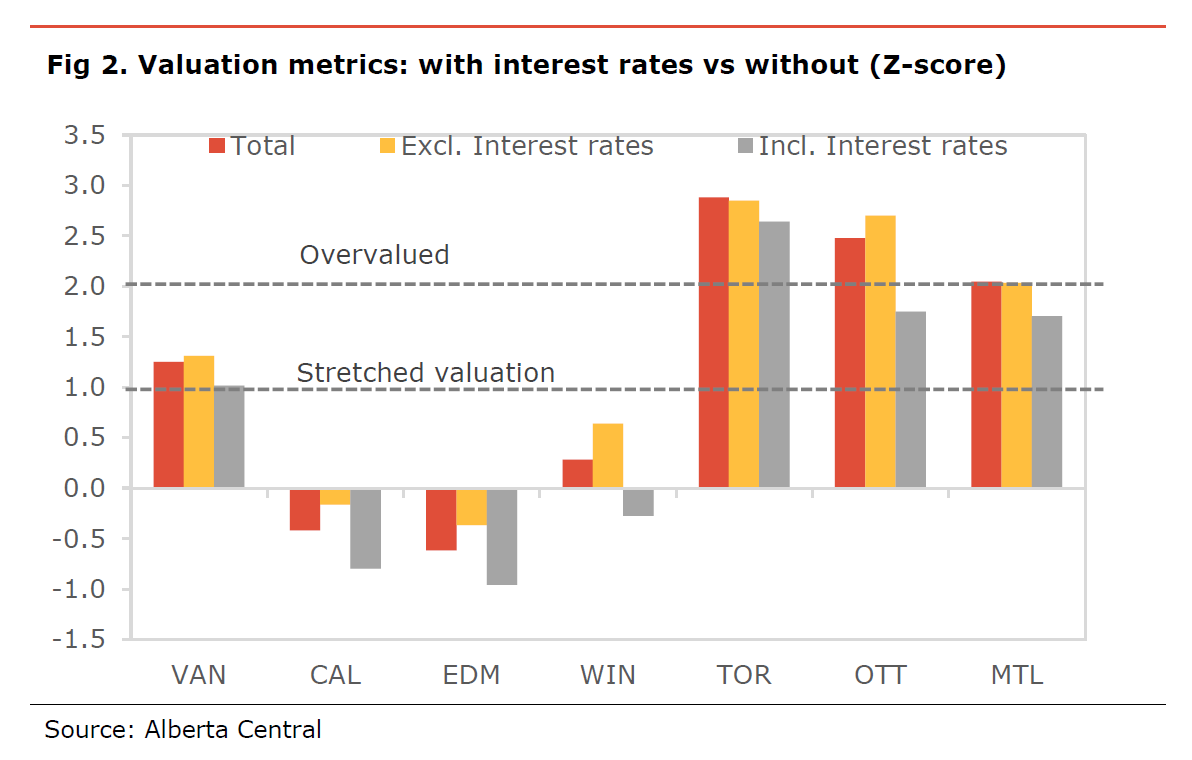

- Moreover, our analysis shows that Toronto remains the most overvalued city in Canada, followed by Ottawa, Montreal and Vancouver. At the other end of the spectrum, there are no signs of overvaluation in Edmonton, Winnipeg or Calgary.

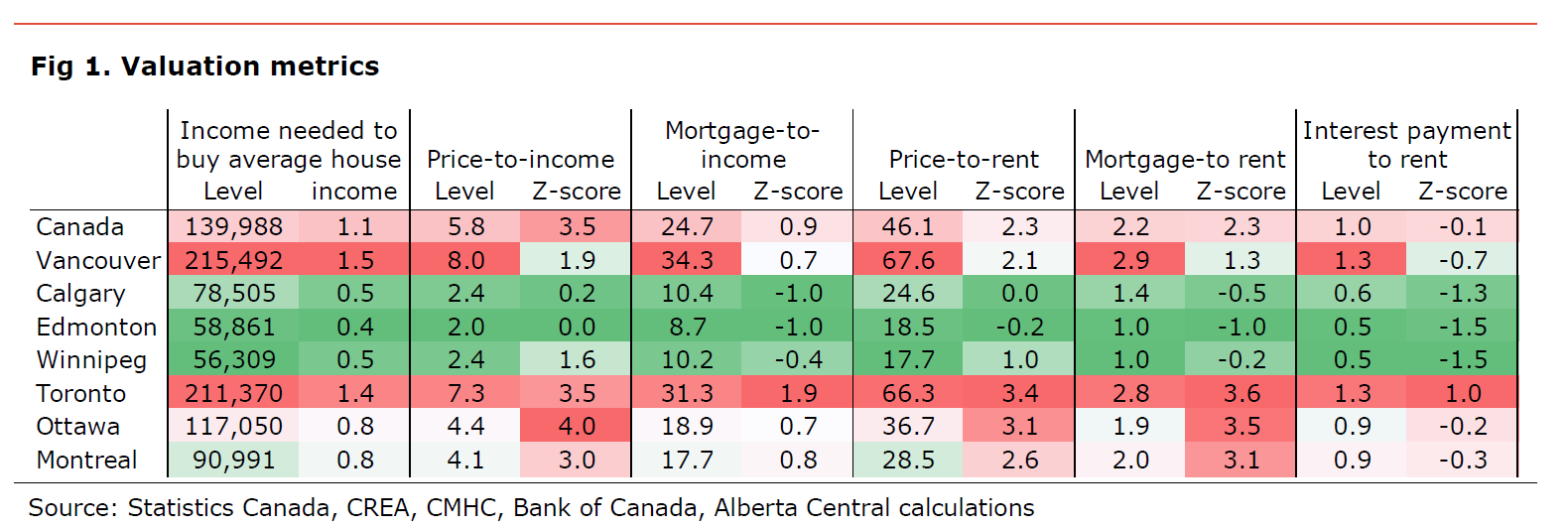

- As such, a family income of $216,000 is needed in Vancouver to afford the average house, the most expensive city. In Toronto, this amount is $211,000. In contrast, the income required is $56,000 in Winnipeg, $59,000 in Edmonton and $78,500 in Calgary, making these cities the most affordable.

- With record low interest rates being the main source of affordability in most cities, an important question for the housing market is whether valuation will be impacted by higher interest rates?

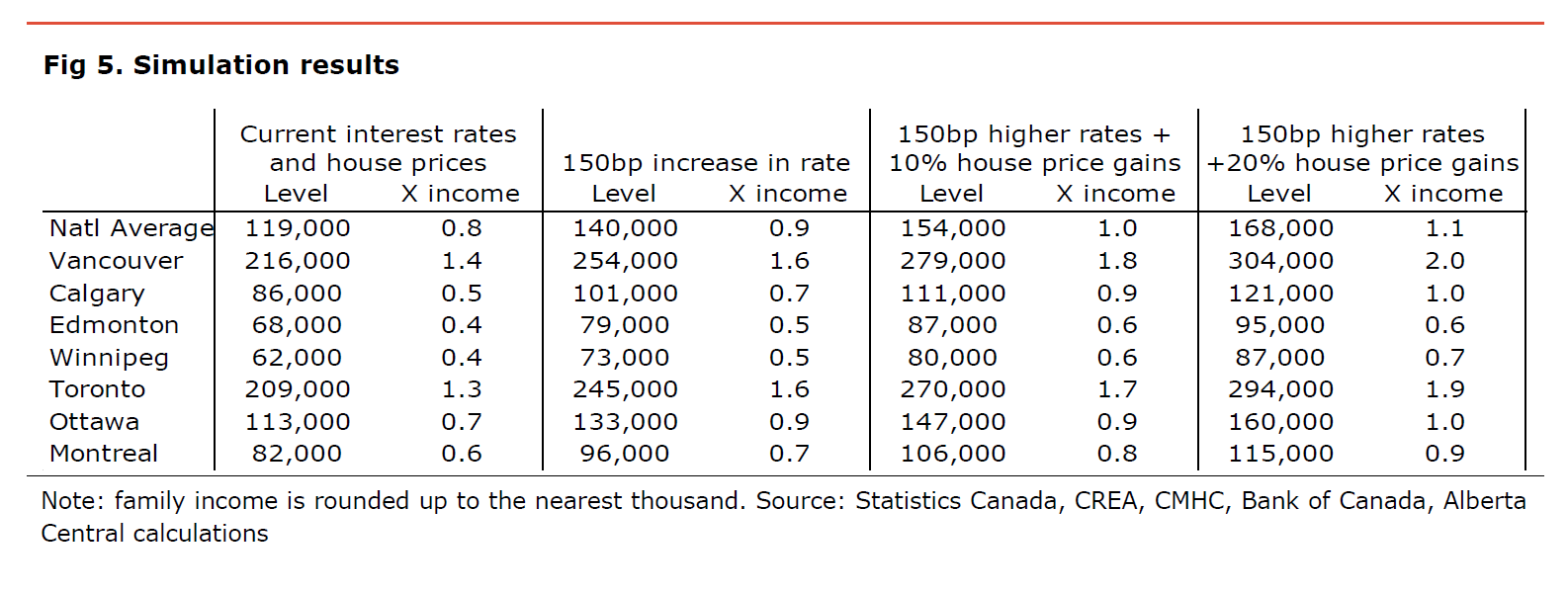

- Our simulations show that many cities in Canada will see a significant erosion in housing affordability as interest rates increase. As such, an 150bp increase in mortgage rates would push the minimum income required to buy the average house in Vancouver to $256,000 (1.6 times average family income). In Toronto, it would increase to $245,000 (1.5 times average family income). In Calgary, Edmonton and Winnipeg, it would rise to $101,000 (0.5 times income), $79,000 (0.5 times income), and $73,000 (0.6 times income), respectively, making them the most affordable cities. Any increases in house prices would only exacerbate the deterioration in affordability.

- Any increase in interest rates and house prices will challenge affordability in some cities and price out many would-be buyers, leading to a moderation in demand and weaker resale activity.

- The impact of higher interest rates will mainly be felt by new buyers and those with variable rate mortgages. The introduction of the stress-test in 2018 reduced the likelihood of financial stress on current borrowers that would have lead to forced selling and potentially house price declines.

- With many buyers likely to be priced out of owning a house, demand for rentals will increase in many cities. This situation is likely to lead to higher rent and put upside pressures on inflation in the coming years.

- The slowdown in housing activity due to eroding affordability could impact monetary policy and could mean a slower pace of rate hikes and a lower terminal rate. However, weaker housing activity will not deter the BoC’s resolve to control inflation. After all, a moderation in the housing market would be part of that reduction in aggregate demand needed to offset the supply-induced inflationary pressures.

- With one of the most affordable housing markets, Alberta is likely to benefit from the situation. First, it may lead to some households priced out in other parts of the country to relocate to the province, leading to an increase in interprovincial migration. Second, with some of the lowest house prices relative to rent, we could see an influx of investors in search of a better return compared to Toronto and Vancouver into Alberta’s housing market.

- With better affordability, positive migration, an influx of investors and positive local economic conditions, we believe that the Alberta housing market is likely to remain strong despite the increase in interest rates this year.

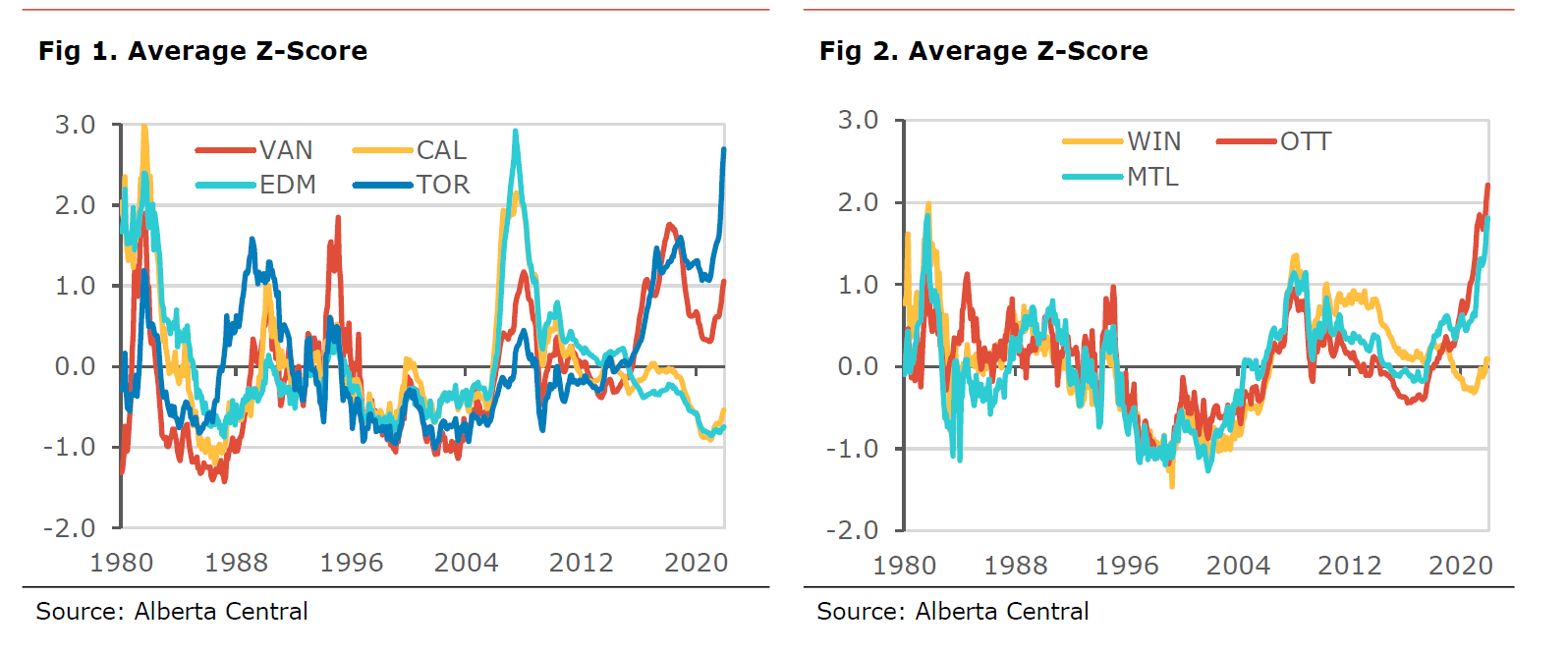

Back in June last year, we published a piece taking a deep dive into various valuation metrics for the housing market (see here).

Since publishing the report, house prices in Canada, as measured by the Canadian Real Estate Association’s benchmark price, have increased by 17% on average in Canada. However, some cities have seen extreme appreciations. For example, house prices in Toronto have increased by 24% while prices in Edmonton increased a more modest 1.6%.

At the time of publishing our original report, we noted that several housing markets will face strong headwinds once interest rates start to increase. With the Bank of Canada (BoC) expected to start raising its policy rate in March and to reach 1.25% by the end of the year, we believe now would be a good occasion to update our simulations regarding the impact of higher interest rates on affordability.

Valuation metrics

We follow the same methodology as used in our original report. This means that we look at the valuation metrics at a metropolitan level. As such, our analysis continues to focus on the main metropolitan areas of Canada: Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal. Altogether, these seven cities cover about 50% of the Canadian population.

We also continue to use the same valuation metrics as in the original piece: house price relative to income, house price relative to rent, mortgage payments relative to income and mortgage payments relative to rent. (See Appendix, available in the Members Area, for more).

In addition, to provide a better understanding of the impact of the high level of house prices, we also introduced a new valuation metric to our study: an estimate of required family income to keep mortgage payments below 25% of income, at current interest rates. The idea behind this measure is that banks will usually require total housing costs (mortgage, property taxes, insurance, condo fees and heating costs) to be below 30% of income to qualify for a mortgage.

Whether an asset is overvalued or not is often subjective as there are no defined levels. Therefore, we focus on the difference between current prices and “normal” prices, or the level of various indicators over the past 40 years. For this reason, we focus on the deviation of the various metrics relative to their historical mean using the Z-score (see Appendix, available in the Members Area, for background on Z-score).

This point is important because housing markets are local and depend on local conditions. For example, conditions in Vancouver have meant that prices have generally been higher than elsewhere in the country for the past four decades. Yet, someone living in the city knows and understands that this is the reality of living there and will plan accordingly. Someone in Vancouver is unlikely to consider a house in Winnipeg or Edmonton, even if the real estate is much cheaper, because commuting is practically impossible due to the commuting cost[1].

However, an important caveat can be made here. As housing is becoming expensive in many cities, there may be individuals buying properties in more affordable cities as investment properties. As such, those investors are likely to be attracted to housing markets where the ratio of prices relative to rent is low (more on this later).

Key valuation findings:

- There continues to be a difference between measures that include interest rates and those that do not. The average Z-score for house prices relative to income suggests overvaluation in many cities. However, when considering mortgage payment relative to income, the Z-score is much lower; Toronto being the exception. This means that affordability is less of an issue, at current record low interest rate levels, and less than back in our original study in June 2021.

- Using our latest valuation metric, a family would need an income of a little more than $215,000 (about 1.4 times the average family income) to afford the average house in Vancouver. This amount is a little more than $211,000 in Toronto (about 1.3 times the average family income) and $117,000 in Ottawa (about 0.7 times the average family income). At the other end of the spectrum, a family income of a little more than $56,000 and of about $59,000 (0.4 times the average family income in both cases) would be required in Winnipeg and Edmonton, respectively. It is important to stress that these levels of income are at current interest rates and will increase as interest rates rise. In Calgary, it is $86,000 (0.5 times the average family income).

- It can be argued that a housing market is becoming unaffordable when more than the average family income is needed to buy the average house. Based on this definition, Toronto and Vancouver are currently unaffordable, while there are no major affordability concerns in other cities. However, this result depends on current house prices and interest rates.

- Despite record low mortgage rates, the average new buyer in Vancouver would be expected to spend almost 35% of its income on their mortgage payment. In Toronto, it is slightly above 30%. Those payments do not even include other essential housing costs such as property taxes, home insurance, utilities and maintenance costs. As a comparison, the average new buyer in Calgary, Winnipeg and Edmonton would be expected to pay 10%.

- Across the various valuation measures, Toronto comes in as the least affordable city in our sample. The city has both elevated measures in absolute terms and relative to history, making it the least affordable city in our analysis. Moreover, even when only considering the metrics that include interest rates, valuation in the city is in overvalued territory.

- However, an interesting point in Toronto is that, while its valuation measures are at all-time highs, they are still marginally below Vancouver. Moreover, while elevated, the level of the indicators in Vancouver is not at an all-time high. This could have important implications: it could indicate a shift in the long-term equilibrium in house prices relative to income and rent and do not necessarily mean that a correction is required to bring back the market to equilibrium.

- A very similar observation can be made for Ottawa and Montreal. Both have Z-scores well in excess of 2, suggesting that the metrics are at all-time highs. However, their levels are still well below those observed in Vancouver and Toronto. Again, this could be the result of a shift in the long-term equilibrium.

- At the other end of the spectrum, Edmonton was the most affordable city, followed by Calgary and Winnipeg. All of these cities rank the lowest both in terms of level and Z-scores. When considering measures that do not take into account the impact of interest rates, the levels of the metrics are only slightly above their historical average. Once interest rates are incorporated, the Z-score in negative territory suggests that affordability in these cities is better than the average.

These findings continue to show that record low interest rates are helping affordability in many cities. This situation is particularly acute in Vancouver, Ottawa and, Montreal. It continues to raise concerns regarding what will happen to the housing market when interest rates inevitably increase. In Toronto, the housing market is already overvalued even when considering the low level of interest rates. This raises serious concern regarding the impact of increasing interest rates this year.

It also points to a situation where the biggest hindrance to affordability at the moment is the higher level of down payment relative to income. As such, an average family in Toronto would need to save three-quarters of its annual income to accumulate the minimum down payment of 10%. This proportion is about four-fifths of annual income for Vancouver, while it is about a quarter in Calgary and Winnipeg.

Simulations

As we showed, interest rates continue to keep affordability closer to their historical averages in many cities in Canada, despite sharp house price increases over the past year. However, with the Bank of Canada set to start to remove some of its monetary stimulus in the coming months, interest rates will rise. Therefore, an important question for the housing market is how much can we expect affordability to be impacted by higher interest rates?

Using the metrics used previously (and outlined in the Appendix), we conduct a series of simulations to estimate the impact of rising interest rates and changes in house prices on the valuation measures. Since our aim is mainly to evaluate the effect of interest rate hikes, we will focus on the metrics of the minimum family income needed to afford the average home .

The simulations are conducted by varying both the interest rates and house prices, allowing us to show the combined impact of both variables, leaving other parameters unchanged. It also provides an estimate of how much house prices would need to decline to compensate for the reduction in affordability coming from higher interest rates or how much further increases in house prices will affect affordability. All the simulations leave the level of income and rent unchanged from their latest values.

Key simulation results:

- Currently, on a national scale, $119,000 is needed or 0.8 times the average family income. If interest rates increase by 150bp, as currently expected by financial markets by year-end, the income required would jump to $140,000 (0.9 times family income), assuming house prices remain the same. But if house prices also increase by 10% over the period, the minimum income jumps to $154,000 (1 time family income); if prices jump higher by 20%, it would be $168,000 (1.1 times family income).

- The national measure masks some stark divergences between cities (see Appendix for full results). The increase in required income is much smaller for Calgary, Edmonton and Winnipeg. Even a 150bp increase in interest rates coupled with a 20% house price increase would leave the required income to buy the average house in these cities below the average family income. As such, required income to purchase the average house would be $121,000 in Calgary, $95,000 in Edmonton and $87,000 in Winnipeg.

- Toronto and Vancouver are already in unaffordable territory at current level of interest rates and house price, with a ratio of required income to average income at 1.3 and 1.4, respectively. If interest rates increase by 150bp and house prices increase another 20%, this ratio would reach 2 in Vancouver and slightly below in Toronto, for a required income of $304,000 and $294,000, respectively.

- In Ottawa and Montreal, it is clear that further house price increase coupled with higher interest rates will make these cities unaffordable. As such, the ratio of the income required relative to the average income will increase above 1 in Ottawa if interest rates rise by 150bp and house prices increase another 20%.

Economic impact

The main conclusion from the simulation is that, as interest rates increase, we will witness an erosion in affordability. This will be particularly the case in cities where house price relative to income are the highest: Vancouver, Toronto, Ottawa and, to a lesser extent, Montreal.

Although we expect the Bank of Canada to increase its policy rate by 125bp, the market thinks it could rise by almost 150bp by year-end. Such increases will erode affordability, especially in Vancouver, Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal. However, it does not necessarily mean a collapse in these housing markets.

We believe it is likely to lead to a moderation in demand and resale activity. It is clear from these simulations that any increase in interest rates will challenge affordability in some cities and price out many would-be buyers. Any further increase in house prices would only exacerbate the deterioration in affordability.

Will house prices fall and insolvencies increase?

For prices to drop, we would need to see a sharp rise in supply likely resulting from homeowners being forced to sell their house because of financial stress. While such an outcome cannot be ruled out, rising interest rates would only impact new buyers, those with flexible mortgages and those renewing their mortgages at higher interest rates.

For existing mortgage holders, most of them have been subjected to the stress-test, introduced in 2018, where the borrower needs to qualify at a higher interest rate, thereby reducing the likelihood of delinquency as interest rates rise. Moreover, for a borrower with a fixed rate mortgage, mortgage rates are currently lower than where they were 5 years ago, meaning that those renewing currently are likely to be offered a lower interest rate than they had.

Nevertheless, bigger mortgage payments as rates increase will lead to households needing to spend more of their income towards debt repayment, leading to a reduction of spending on discretionary spending. This situation will be a headwind on consumer spending in years to come. However, the sizeable amount of savings accumulated during the pandemic could provide some support to spending.

The valuation metrics and simulations also suggest another potential economic development in the coming years: rents have the potential to increase sharply.

- As interest rates go up and households become increasingly priced out from the housing market, demand for rentals is likely to increase, putting upside pressures on rents.

- Rental prices relative to income ratios in many cities are below their long-term average. This is partly the result of rental prices underperforming over the past year, as many renters decided to leave cities or purchase homes during the pandemic. However, some mean-reversion could be expected, especially as the cost of owning will be pushed higher by increasing interest rates.

The amount of pressure on rental costs will also depend heavily on demographics, especially immigration, and on the supply of new rental units. Nevertheless, increasing rents could be a source of inflation and reduction in purchasing power in coming years.

Impact on monetary policy

This situation could also have an impact on monetary policy. It will likely mean that rate increases may need to be gradual to allow the housing market to adjust. Moreover, the terminal rate will likely be lower than in previous rate cycles because of the negative feedback loop between rising interest rates, higher mortgage payments and lower discretionary spending.

However, it doesn’t mean that a slowdown or even a drop in activity in the housing market would deter the BoC to hike rates. In the current environment, the central bank’s main priority is controlling inflation. As long as inflation remains above its target and the future trajectory remains uncertain, the housing market will be of secondary importance in its view.

Moreover, in the context of supply-induced inflation, reducing inflationary pressures requires a decline in demand (see). A moderation in the housing market would be part of that reduction in demand and normally expected. Hence, the BoC wouldn’t react to weakness in the resale market. Where the BoC could be compelled to slow the pace of its policy normalization is if there were signs that higher interest rates are leading to increased financial strains on household, increasing the risk of a significant increase in defaults.

Impact on Alberta

Although some of the most affordable housing markets in Alberta are unlikely to see a major direct impact from rising interest rates, we note that we are already seeing the impact of better affordability in Alberta relative to other housing markets in the country.

- There is some evidence that some buyers priced out of the housing markets in Ontario and BC are starting to move to Alberta to take advantage of lower house prices. The pandemic is also facilitating such decisions with many employers allowing employees to work remotely. The latest inter-provincial migration statistics have shown a strong positive influx of migrants from other provinces in 2022Q3, the strongest since 2015.

- Similarly, we are starting to see some evidence of housing investors’ purchases in the province, especially in Calgary. With one of the lowest levels of house prices relative to rent in Calgary and Edmonton, such a situation increases the likelihood of positive returns on investment for those investors, especially compared to cities like Toronto and Vancouver. To put it into perspective, it takes 25 years of rent payments to cover the cost of the average house in Calgary, while it takes 68 years and 66 years in Vancouver and Toronto, respectively. Moreover, Alberta offers some of the most landlord-friendly regulations in Canada.

All these factors, plus an improvement in the local economy thanks partly to the tailwind from higher oil production value means that the housing market is likely to remain stronger in Alberta than in the rest of the country as interest rates increase. It will also have a positive feedback loop to the rest of the economy if we continue to see positive net interprovincial migration numbers.

Conclusion

The valuation metrics and the simulations show that the current low interest rates remain a significant driver for the housing market by keeping affordability high despite elevated and increasing house prices. However, interest rates are to increase soon, with the Bank of Canada expected to hike its policy rate in the second half of 2022.

Our simulations show that a rise in mortgage rates doesn’t need to be significant before some headwinds on the housing market begin to be felt. For example, in many cities, a 150bp increase could push the valuation metrics into overvalued territory. In the case of Toronto, it is already in overvalued territory. However, this doesn’t mean that we will see prices collapse; rather, this will likely lead to a housing market stagnation.

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.