Economic insight provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Main takeaways

- Last year, inflation reached levels not seen since the 1980s. A sharp rise in energy prices is partly to blame for the sharp rise in inflation.

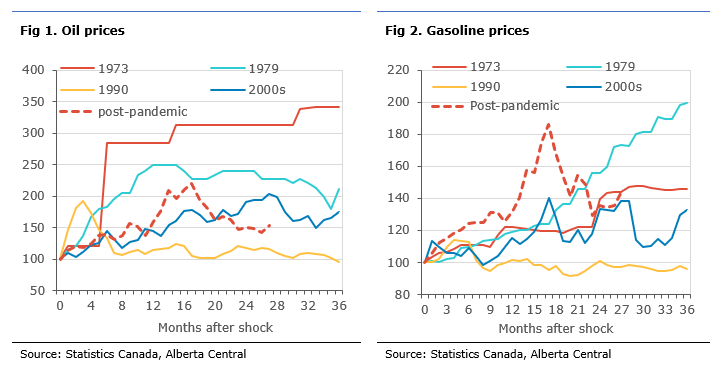

- Comparing the post-pandemic energy shock to other similar episodes in Canadian history, we find that the increase in oil prices in 2021-2022 was not as significant as during the two oil shocks of the 1970s.

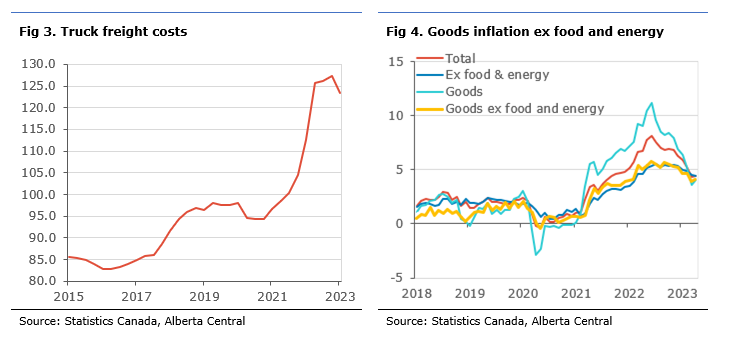

- However, looking at the impact the surge in oil prices has had on the price of end-products, like gasoline, we find that the post-pandemic energy shock resulted in the fastest and sharpest surge in gasoline prices in recent history.

- Although gasoline prices are lower than last year, thereby producing a drag on inflation, focusing on the year-over-year change misses the fact that their levels remain about 30% above their pre-pandemic level, leading to important spillovers to other prices in the economy.

- For example, transportation costs are much higher than before the pandemic, with trucking freight costs about 25% higher.

- In a vast country like Canada, where everything needs to be transported, transportation costs are a major input cost for many businesses.

- The impact of higher energy and transportation costs is likely non-linear. The bigger the shock, the more it compresses businesses’ profit margins and, as more of the costs will need to passed onto customers, there is a faster and/or bigger pass-through from higher fuel costs to other prices in the economy. The high inflation environment also facilitates the pass-through as customers expect price increases.

- The result is higher prices for many goods, from food that needs to be hauled from Mexico to imported goods that arrive on the west coast and need to be shipped thousands of kilometres to consumers in middle Canada.

- In addition to goods, services can also be affected since both natural gas and non-residential electricity prices are well above their pre-pandemic levels.

- A critical question for the outlook for inflation is whether a stronger second-round effect from the higher energy costs could offset part of the easing in inflationary pressures coming from normalization in the global supply chain.

- The continued impact of the sharp rise in energy prices could explain, in part, the stickier inflation than initially expected. Such an outcome would require further monetary tightening by the Bank of Canada.

- In our view, this could support further rate increases this year, especially in light of continued resilience in the demand side of the economy, with robust consumer spending and labour market. Furthermore, it could justify the BoC to hike again sooner rather than later.

Inflation reached 8.1% in July 2022, its highest level since the early 1980s; the sharp rise in energy costs is partly to blame, with inflation excluding energy peaking at 6.3% in September 2022 and inflation excluding gasoline reaching 6.6% in July 2022). However, these numbers do not take into account the spillovers and second-round impact of this sharp increase in energy costs on other prices in the economy. One little-mentioned fact is that the post-pandemic energy shock had a bigger and more rapid impact on inflation than any other energy shock in recent Canadian history, including the two oil shocks of the 1970s. As a result, we can expect that the impact on prices in the broader economy may have also been of a bigger magnitude than in the previous episodes and could explain the persistence in core measures of inflation.

Comparing oil shocks

The sharp rise in oil prices during the post-pandemic period needs to be put into perspective relative to other energy shocks in history. To do so, we consider five episodes of sharp rises in oil prices:

- 1973’s oil shock: Often referred to as the First Oil Shock, this disruption began in October 1973 when the members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) proclaimed an oil embargo targeted at nations that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War. As a result, WTI prices surged from $3.56 a barrel in the summer of 1973 to $10.11 by the start of 1974, an increase of almost 300%.

- 1979’s oil shock: A sharp decline in oil production following the Iranian Revolution led to a sharp increase in oil prices, rising from $15.85 to $39.50 within a year.

- The 1990 invasion of Kuwait: Following the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq in August 1990, oil prices temporarily doubled over the following three months but normalized thereafter.

- The constant rise in price in the 2000s: After reaching $40 a barrel in July 2004, oil prices rose constantly over the next four years, reaching a high of $145 in 2008.

- Post-pandemic surge and the invasion of Ukraine: This period is from the moment oil prices surpassed their pre-pandemic level in February 2021 to now. (The preceding period is not included as it was mainly a correction of the sharp drop at the start of the pandemic.)

Figure 1 shows all five episodes relative to each other. Both oil shocks of the 1970s would rank as the biggest and most persistent increases in oil prices. The post-pandemic episode would rank as the third most important when considering the peak increase. However, while oil prices are about 50% above their pre-pandemic level, the shock has not been very persistent, with prices having retracted over the past year. Moreover, about two and half years after the initial shock, oil prices in the mid-2000s had increased more by this point than they have over the post-pandemic period.

End-user price levels matter for inflation, not just the change

While the price of oil is important to the economy, what matters is what end-users – consumers and businesses – pay for the end product, gasoline. Looking at the evolution of gasoline prices during the five oil shock episodes (Fig 2), we see that the post-pandemic period has seen the fastest and sharpest surge in gasoline prices, jumping 80% higher over the period. While gasoline prices have eased over the past year, in line with lower oil prices, they remain about 40% above their pre-COVID levels, despite oil prices being less than 20% above their pre-pandemic level. Similar moves are also observed in diesel prices.

A lot of the focus has been on the direct impact of gasoline prices on inflation. In this case, it is the change in prices compared to the previous year that matters. Currently, energy prices are a drag on inflation since they are lower than during the same period last year. While this is correct to evaluate the first-round impact of higher gasoline prices on inflation, it ignores that the change in price level may matter more for the second-round effect; i.e. how it will spill over to other prices in the economy.

In a country like Canada, most consumer goods must be hauled over long distances either by trucks or trains, making transportation costs a significant input cost for most goods and businesses. As a result, higher fuel prices and transportation costs have a direct impact on businesses’ profit margins.

In periods of smaller increases in energy prices, the rise in cost is small and likely absorbed by businesses for some time by compressing profit margins to maintain competitiveness. However, the impact is likely non-linear; the bigger the shock, the more likely a business will need to pass the extra cost onto its customers. This likely lead to a faster and/or bigger pass-through from higher fuel costs to other prices in the economy. In addition, in a high inflation environment, it is likely easier to pass rising costs onto customers as their inflation expectations are higher.

The impact of the sharp rise in gasoline prices in 2021, with prices reaching levels about 80% above their pre-pandemic levels and remaining over 40% above their pre-COVID levels, has had a significant impact on transportation costs. As such, truck freight costs are currently still about 25% above their pre-pandemic levels. It is unlikely that businesses can fully absorb these higher costs in their profit margins, meaning that these higher costs have likely been passed on, in part, to customers.

While it is hard to quantify, it is likely that the surge in transportation costs may explain part of the stickiness in inflation. One example is food prices: as most fresh fruits and vegetables need to be hauled from the southern United States and Mexico, transportation is an important source of costs. Even food produced in Canada often has to travel vast distances to reach grocery store shelves. The same can also apply to other goods. Those imported from China need to be hauled from the port of Vancouver to customers throughout the country, a journey involving thousands of kilometres. This can partly explain why inflation for goods, excluding food and energy, has only moderated slightly and remains above 4%.

Services prices are also affected by the energy shock

The impact of higher energy costs is not limited to the prices of goods; it also impacts service prices. Energy prices, other than gasoline, are also significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels, with natural gas prices being about 40% above their pre-pandemic levels, as measured in the CPI, and non-residential electricity prices being 15% higher than pre-pandemic. These higher prices have an important impact on business costs and reduce profit margins. Thus, increasing energy input costs will affect the service industry as well, from financial to legal services and health care to education, due to higher utility costs. The impact is likely smaller than for goods, yet likely still important especially considering the size of the increase.

Could this be the source of inflation stickiness?

A critical question remains for the outlook for inflation. Could persistently higher energy costs lead to stickier inflation? Many analysts expect the normalization of the global supply chain will lead to an easing in inflationary pressures. However, there could be a risk that the second-round impact from higher energy costs and transportation costs could offset these easing inflationary pressures.

As a result, the continued impact of the sharp rise in energy prices and the second-round effects could explain, in part, the stickier inflation than initially expected. Such an outcome would require further monetary tightening by the Bank of Canada. In our view, this could support further rate increases this year, especially in light of continued resilience in the demand side of the economy, with robust consumer spending and labour market. Furthermore, it could justify another BoC hike again sooner rather than later.

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.