Economic insight provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Main takeaways

- Various shocks are squeezing household budgets this year. As a result, many households may need to cut down on spending or draw from their savings.

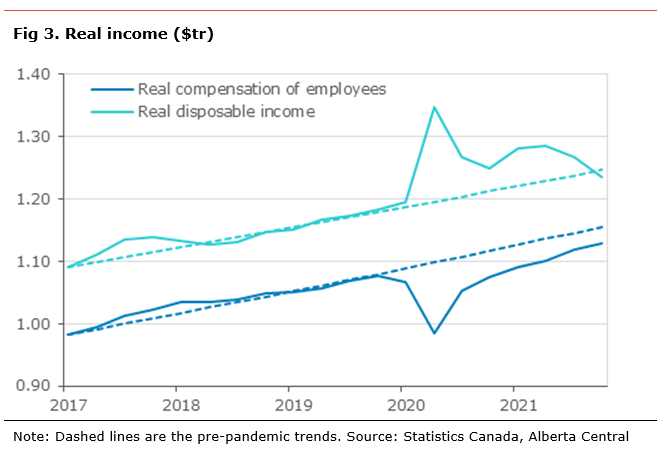

- After being boosted by government programs during the pandemic, household disposable income is normalizing. With government transfers still above their historical average, further easing in household disposable income is expected. In addition, after including the high inflation rate, real disposable income is below where it would be expected, pointing to a loss in purchasing power.

- Inflation is reaching levels not seen since the early 1990s. However, so far, wage gains have been modest, leading to a decline in real wages and real income. Consumers expect inflation to remain above their wage gains over the next year, suggesting that households assume further erosion of their purchasing power.

- The Bank of Canada’s Survey of Consumer Expectations also suggests that workers are dissatisfied with their wages and that many are considering voluntarily leaving their jobs. This could lead to increased churn in the labour market and help raise wage growth as employers try to attract and retain talent with better pay conditions, especially in a context of labour shortages.

- Higher inflation is also leading to fast-rising interest rates. With household indebtedness at an all-time high, the cost of servicing this debt will increase.

- We estimate with each 100bp increase in interest rates on the underlying debt, households would need to divert $6.6bn every quarter to debt repayment at the current level of debt; this would raise the debt service ratio by 1.5 percentage points. This represents almost 2% of households’ total consumption, a reduction in discretionary spending or a drawdown from savings.

- The speed at which higher interest rates will filter into the interest rate charge on outstanding household debt will matter and depends on the proportion of fixed rate versus variable rate.

- We estimate that about 50% of household debt outstanding will incorporate the increase in interest rates if we include both variable rate debt and the debt that needs to be refinanced every year.

- Taking the current market expectations of the policy rate reaching 2.50% by end of 2022 and 3.35% by end of 2023, we estimate that the debt-service ratio is likely to increase to about 15.6% by the end of 2022 and 16.4% by the end of 2023; this is about 1.1pp and 1.8pp higher, respectively, than at the end of 2021. This means that households would pay $7.7bn more in interest every quarter by the end of the year or 2.3% of consumption. By the end of 2023, it would be $11.6bn, or 3.4% of what they consumed, at the end of 2021.

- The risk is that some households may not be able to face the rise in their financial obligations leading to rising insolvencies. However, macroprudential regulations, including the mortgage stress-test, have been important in ensuring that households were prepared to face higher interest rates and could mitigate that risk.

- The large savings accumulated during the pandemic will likely soften the impact of declining purchasing power and rising debt service costs. We estimate that households in Canada have managed to accumulate about $310bn in savings during the pandemic, about $185bn of which is currently held in demand deposits at financial institutions.

- With the most leveraged households in Canada, Alberta is likely to be more affected by the rise in interest rates than the rest of the country. This means bigger headwinds on consumers and their finances.

- However, a higher savings rate and the positive impact of high energy prices on income in the province could somewhat mitigate some of the impact of higher interest rates.

- Consumer spending and some sectors of housing investment will face some important headwinds in the coming years. As a result, there is a risk that growth will be weaker than currently expected. For the overall growth outlook, the question is whether business investment and exports can grow sufficiently to compensate for this weakness.

Consumers are being squeezed in all directions this year by various changes that impact their budget. These shocks to households are: 1) normalization in disposable income as COVID-related programs are gradually winding-down, 2) high inflation eroding purchasing power, and 3) rising interest rates increasing households’ debt-service ratio. The situation could lead to much weaker consumer spending than expected and to a weaker housing sector.

Consumer spending, residential renovations and housing resale activities have been a big driver of the recovery from the pandemic, being responsible for about 75% of growth over the period. Similarly, since the end of the global financial crisis in 2009, both also contributed 1.7pp to growth on average out of 2.3pp. In both cases, these contributions to growth outweigh the importance of these sectors in the economy.

The question for the outlook is whether other sectors, mainly business investment and exports, can grow robustly enough to compensate for a weaker contribution from consumer spending and some of the housing components. However, as we have noted previously, a period when growth is below potential, leading to a negative output gap, will be necessary to fight inflation.

A normalizing disposable income

The COVID recession was atypical. Thanks to the government’s income support programs, it was the first recession in modern history during which we saw a decline in workers’ compensation while at the same time witnessing an increase in disposable income. Moreover, as a result of the rise in disposable income, the average household in Canada was better off during the pandemic than before.

With the recovery well underway, many programs are being phased out or becoming less generous. As a result, we saw a normalization in disposable income, declining for two consecutive quarters in the second half of 2021 (1.3% q-o-q in the fourth quarter of 2021).

While disposable income is back to where it should have been if it had grown at its pre-pandemic trend, the normalization is yet fully complete. The share of government transfers in disposable income is still slightly above its pre-pandemic level at 19% vs. 17%, suggesting some more adjustment is likely.

In addition, adjusted for inflation using the deflator on household consumption, real disposable income declined by 2.4% q-o-q in the fourth quarter and is now below its pre-covid trend, suggesting an erosion in households’ purchasing power over the recent quarter.

With inflation accelerating in the first quarter of 2022, CPI-inflation likely went from 1.4% q-o-q in 2021Q4 to 1.8% q-o-q in 2022Q1, a decline in real disposable income is very likely, further eroding the purchasing power.

Eroding purchasing power

Inflation in Canada has been on an increasing trend over the past year, rising from 2.2% to 6.7%. While higher inflation was seen as temporary and limited to certain categories, especially energy costs, it is now becoming more permanent and broader, with about two-thirds of CPI components rising at more than 3% y-o-y.

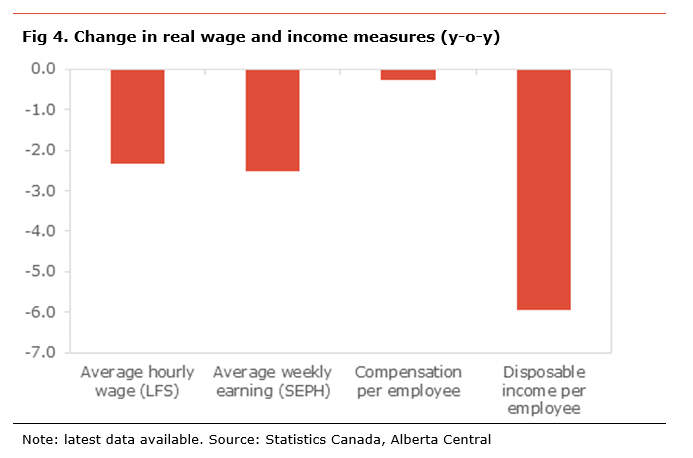

However, wage growth in the country remains relatively subdued and has not yet caught up to inflation. This means that many households are seeing a decline in their purchasing power. Looking at various measures of wages and income, households have seen a decline in purchasing power of between 0.3% and 5.9% over the past year, depending on the measure considered (see Fig 4). Moreover, with inflation expected to stay close to 6% until the summer and to remain above the top-end of the BoC’s target, further erosion in purchasing power is likely unless wage growth picks up.

The latest BoC Survey of Consumer Expectations shows that, while consumers expect inflation to be 5% in a year, wages are only expected to grow 2.2%. Similarly, almost 60% of the consumers surveyed say that their wages increased slower than inflation. This suggests that households expect their purchasing power to deteriorate further. Interestingly, the survey shows that most consumers are not satisfied with their most recent wage adjustment.

The erosion in purchasing power, weak wage growth and dissatisfaction with pay will likely lead to more disruption in the labour market. Workers are likely to increasingly look elsewhere for better pay conditions which could increase the churn in the labour market. The BoC’s Survey of Consumer Expectations shows that workers are increasingly likely to leave their job over the next 12 months voluntarily. With many employers reporting labour shortages, improving pay conditions will likely be a tactic to retain and attract talent.

The question is whether pay increases will reverse the purchasing power loss. However, accelerating wage growth is likely to become a concern for the Bank of Canada, as it could be a sign that higher inflation is becoming entrenched in inflation expectations, necessitating more aggressive rate increases.

Increasing debt-service costs

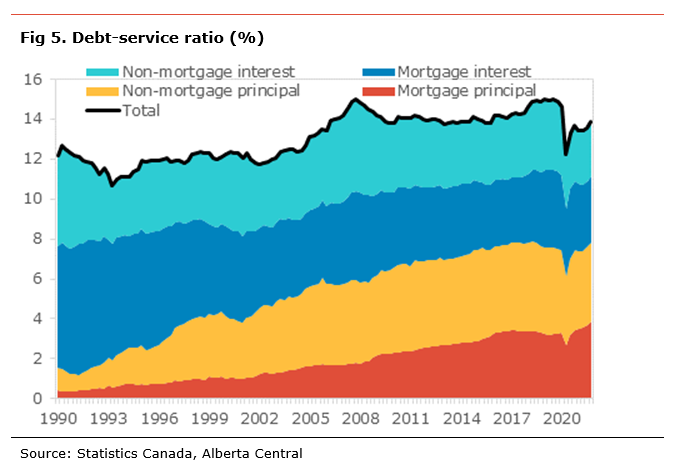

Households in Canada are heavily indebted, with a total amount of debt of $2.6 trillion or about $84,500 per Canadian aged 15 and over. The debt-to-disposable income reached a record at about 186% in 2021Q4. This ratio has increased by about 10 percentage points over the past decade. Most of the increase has been in mortgage debt. The share of mortgage debt in total household debt increased from 63% to a current share of 74% over that period. Higher house prices explain part of the increase (ratio of mortgage debt to house prices).

Because of the high level of debt, households are currently spending almost 14% of their disposable income to service their debt. The debt-service ratio has been hovering around this level since the global financial crisis, except for a brief period of around 15% between 2018-2019 due to increasing interest rates.

The composition of these debt-service payments also changes drastically because of the bigger debt holding. Currently, 7.9 percentage points (pp) – more than half of the debt service payments – are obligated principal repayment; this proportion was only 6.5pp in 2011. As a result of the high level of debt, increasing interest rates will push the interest payment higher.

How will rate hikes impact the debt service?

We estimate that a 100bp increase in interest rates on the underlying debt, the debt-service rate rises to 15.3%, its highest on record. This would mean that households would need to divert $6.6bn every quarter to debt repayment at the current level of debt. This represents almost 2% of households’ consumption, requiring a shift in families’ budgets with a reduction in discretionary spending or a drawdown from savings.

However, financial markets expect the BoC to increase its policy rate by at least 150bp to 2.5% by the end of 2022 and another 75bp to 3.25% by 2023. The last time the policy rate was at 2.00% was in 2008; the underlying interest rate on mortgage debt outstanding was almost 5% and it was 8.25% for non-mortgage debt. Applying the market-implied rise in the policy rate of 225bp on today’s level of debt, the debt-service ratio would jump to 17.1% and households would need to spend $11.0bn per quarter (3.2% of their consumption) in increased interest payments.

How quickly will rising rates pass through to the debt service?

It is important to note that rises in the BoC’s policy rate will not immediately and fully increase the rate on the outstanding household debt. The speed of the pass-through from higher market interest rates to higher payments depends on whether the debt is fixed or variable.

In the case of variable rate products, interest rates are generally linked to the chartered banks’ prime rate, which usually moves in tandem with the BoC’s policy rate. In the case of fixed-rate lending, higher rates will only gradually make their way onto higher payments as the debt is renewed or new loans are taken.

Currently, about 30% of outstanding mortgages are at variable rates. However, over the past six months, about 50% of new mortgages are variable, despite the rising likelihood that the BoC would increase interest rates sooner rather than later. This is because the spread between fixed and variable rates widened to more than 100bp in late 2022, making variable rates more attractive. Moreover, when looking at fixed rates mortgages, roughly 65% had an original term of 5 years or over and 27% had a term of between 3 to 5 years. This means that a little more than 20% of fixed rate mortgages likely need to be refinanced every year or about 15% of all outstanding mortgages. Based on these estimates, about 45% of all outstanding mortgages will incorporate the increase in interest rates over the upcoming year.

For non-mortgage debt, lines of credit, both secured and unsecured, represent a little more than 60% of outstanding debt. The interest rate on this type of lending is usually linked to the prime rate and will fully incorporate rate increase as they occur. The rest of non-mortgage debt is mainly car loans and other personal loans that tend to be fixed.

Combining mortgages and consumer credit, we estimate that almost 40% of household debt is at variable rate and will immediately incorporate any increases in the BoC’s policy rate. If we include the mortgages that will need to be refinanced over the next year, this share reaches about 50% of all household debt.

Using this current composition of debt, debt level and disposable income, using market expectations of the policy rate at 2.5% by end-2022 and 3.25% by mid-2023, we estimate that the debt-service ratio is likely to increase to about 15.6% by the end of 2022 and 16.4% by the end of 2023, about 1.1pp and 1.8pp higher than at the end of 2021.

This means that households would pay $7.7bn more in interest every quarter by the end of the year or 2.3% of consumption. By the end of 2023, it would be $11.6bn, or 3.4% of what they consumed, at the end of 2021.

The chart below shows how the debt-service ratio could increase in the coming years as higher interest rates filter into higher interest payments.

The risk is that some households may not be able to face the rise in their financial obligations leading to rising insolvencies. However, macroprudential regulations, including the mortgage stress-test, have been important in ensuring that households were prepared to face higher interest rates and could mitigate that risk.

Saving accumulated during the pandemic to ease tensions

The large savings accumulated during the pandemic will likely soften the impact of declining purchasing power and rising debt service costs. We estimate that households in Canada have managed to accumulate about $310bn in savings during the pandemic due to weaker spending and higher disposable income. We also estimate that about $185bn of this saving is currently held in demand deposits at financial institutions, the rest having been invested.

To put the amount of savings into perspective, an inflation rate of 7% means that households need to spend about $96.5bn more to purchase the same basket of goods. This means that households have accumulated enough easily accessible savings to maintain their consumption if they use available resources.

Similarly, with interest payments rising by $7.8bn per quarter by the end of 2022, the savings accumulated in demand deposits could easily cover payments for many months. Based on our previous simulation, households could use their liquid savings to cover the higher interest payment costs until at least the end of 2024.

However, not every household will be affected in the same way. For example, the households having managed to accumulate savings during the pandemic are not necessarily those who will see the biggest rise in interest payments or loss in purchasing power.

Albertans are more at risk from rising interest rates

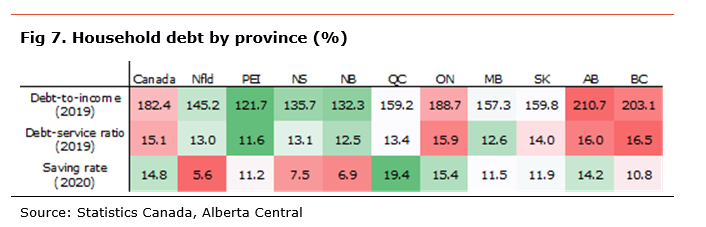

Households in Alberta are the most leveraged in Canada. Going into the pandemic in 2019, the debt-to-disposable income for Alberta was 211%, well above the national measure of 182%. About 65% of household debt in Alberta debt is mortgages debt.

As a comparison, BC, the second most indebted province, has a debt-to-disposable income ratio of 203%. As a result of the high level of debt, Albertans were spending 15.7% of their income to service their debt in 2019, second to BC at 16.1%

Using these numbers, we estimate that the debt service ratio in the province could jump to 16.3% by the end of the year and to 16.9% by the end of 2023. In comparison, we estimate that it could reach 16.8% and 16.3% for BC and Ontario, respectively, in 2022. For 2023, the ratio could be 17.4% and 16.9%, respectively. The smaller increase in Alberta is the result of a higher proportion of non-mortgage debt that tends to be less sensitive to rising interest rates.

While the increase in the debt-service ratio is likely to be smaller in Alberta, it will still impact household finance and force households to reduce their discretionary spending. However, the higher saving rate in Alberta relative to other provinces could help soften the negative impact on consumers and reduce the risk of consumers defaulting on their financial obligations.

Moreover, high energy prices are also pointing to a rise in Alberta’s disposable income. Such an improvement is likely to offset at least partly some of the impact of rising interest rates on household finances. However, not every household will benefit equally from higher energy prices, especially since it also leads to increased costs, especially on gasoline and utilities.

Conclusion

Households will feel the pinch from a normalization in income, rising inflation and higher debt costs. As a result, households will likely need to reduce discretionary spending, meaning that the post-pandemic boom in consumption may be smaller than expected. However, the high level of savings could cushion some of the negative impacts, if households use it to keep their spending unchanged.

What is clear is that both consumer spending and some sectors of housing investment will face some important headwinds in the coming years. As a result, there is a risk that growth in these sectors will be weaker than currently expected. For the overall growth outlook, the question is whether business investment and exports can grow sufficiently to compensate for this weakness.

Recent business surveys suggest that businesses are set to increase their level of investment on machinery and equipment to raise their production capacity. This could support growth in the coming quarters. As for exports, with the IMF recently downgrading its expectations for global growth due to the war in Ukraine, the contribution to the sector may be weaker than initially expected. Moreover, as most central banks increase their policy rate to control inflation, continued withdrawal of monetary stimulus is also likely to weigh on global growth.

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.

Alberta Central member credit unions can download a copy of this report in the Members Area here.