Economic insight provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud. This report includes regional details for Alberta.

Bottom line

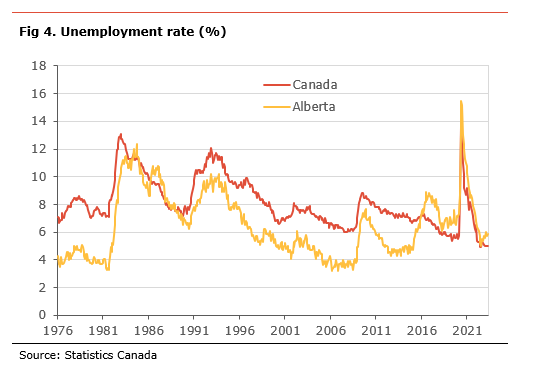

Today’s Labour Force Survey data continues to point to a labour market in Canada that remains robust and resilient. The low unemployment rate continues to signal that the labour market remains very tight, something the Bank of Canada is closely monitoring. Moreover, the report also shows that wage growth remains above 5% and higher than inflation, with average wages increasing by 5.2% y-o-y. However, the 3-month annualized change of the seasonally-adjusted series, at 2.7%, suggests that wage growth is decelerating.

A robust labour market and strong wage growth are a challenge for the Bank of Canada. As we have explained on numerous occasions, the BoC needs to slow growth and create some excess capacity in the economy to fight inflation. This will likely lead to a rise in the unemployment rate and job losses. With this in mind, continued strength and tightness in the labour market may not be a welcomed outcome for the BoC. Moreover, the central bank is becoming increasingly concerned with the disconnect between strong wage growth and weak labour productivity.

The continued resilience of the labour market and the strength in the economy in the early part of 2023 led the BoC to consider increasing its policy rate at the April meeting. However, whether the BoC hikes further depends on inflation and the growth outlook, especially in light of weak growth in the second quarter. Moreover, the continued banking woes in the US and Europe suggest caution is warranted, as the Boc may need to balance fighting against inflation and increased financial stability risks.

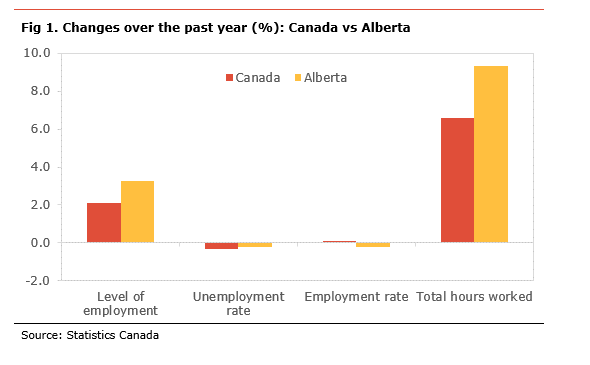

Alberta saw a slight decline in employment in April and the unemployment rate rose to 5.9%. Over the past twelve months, the Alberta labour market has outperformed the rest of the country in terms of job gains. However, the unemployment rate in Alberta remains higher than the national measure. As a result, we observe some continued underperformance in wage growth in Alberta at 2.6% y-o-y, compared to 5.2% y-o-y in the rest of Canada.

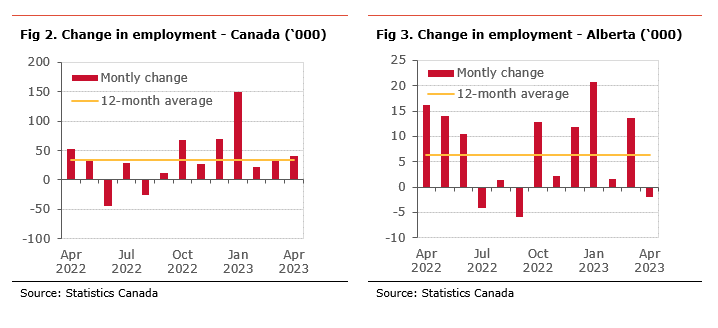

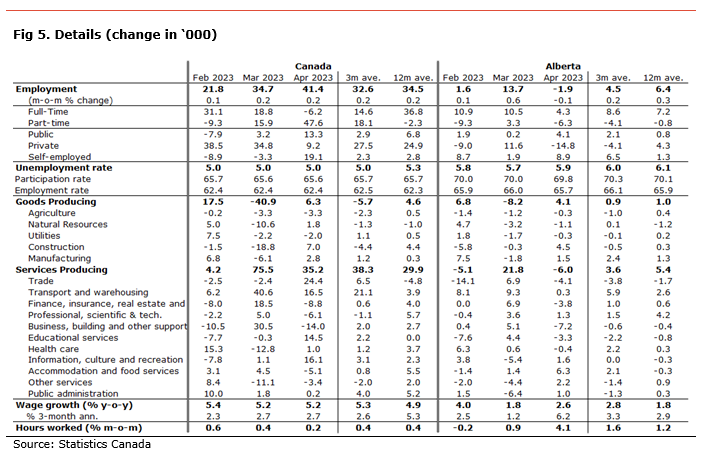

Employment increased by 41.4k in April and continues to be stronger than expectations. The unemployment rate remained at 5.0% for a fifth consecutive month and the participation rate remains unchanged at 65.6%. The participation rate is still 0.3 percentage points (pp) lower than before the pandemic, as workers left the labour force. If the participation was the same as before the pandemic, the unemployment rate would be 5.4%. The employment rate, the share of the population holding a job, was also unchanged at 62.4%, slightly above its pre-COVID level. Wage growth remained at 5.2% y-o-y, remaining above 5%. However, the 3-month annualized change in wages is at 2.7%, suggesting that wage growth is decelerating.

The details show that the job gains in April were all part-time (+47.6k), while there were losses in full-time (-6.2k). In addition, the rise in employment was mostly in self-employed (+19.1k) and the public sector (+13.3k), with a smaller gain in the private sector (+9.2k).

On an industrial level, all the increase in employment was in the service sector (+35.2k), while there was a minor increase in the goods-producing sector (+6.3).

The details in the good-producing sector show that the job gains were, led by construction (+7.0k), manufacturing (+2.8k), and natural resources (+1.8k). These increases were partly offset by losses in agriculture (-3.3k) and utilities (-2.0k).

The increase in the service industry came mainly from gains in trade (+24.4k), transportation and warehousing (+16.5k), information, culture and recreation (+16.1k), and education (+14.5k). These gains were partly offset by losses in business, building and other support (-14.0k), finance, insurance and real estate (-8.8k) and professional, scientific and technical services (-6.1k).

Despite continuous gains in employment and the overall level of employment being above its pre-COVID level by 4.7 percentage points, only 12 out of 16 industries have a level of employment above its pre-pandemic level. The lagging sectors are: agriculture, business, building and other support services, accommodation and food services, and other services. Employment in the accommodation and food services is still almost 10% below its pre-COVID-19 level.

In Alberta, employment eased slightly by 1.9k in April. With continued increase in the labour force and weak job gains, the unemployment rate edged higher to 5.9% from 5.7%, while the participation rate eased to 69.8% from at 70.0%. The participation rate in the province is still 1.3 percentage points (pp) below its pre-pandemic level suggesting many workers are remaining on the sidelines. If the participation rate was at the same level as before the pandemic, the unemployment rate in the province would be 7.5%. The employment rate, the share of the population holding a job, inched lower to 65.7%, marginally below its pre-pandemic level.

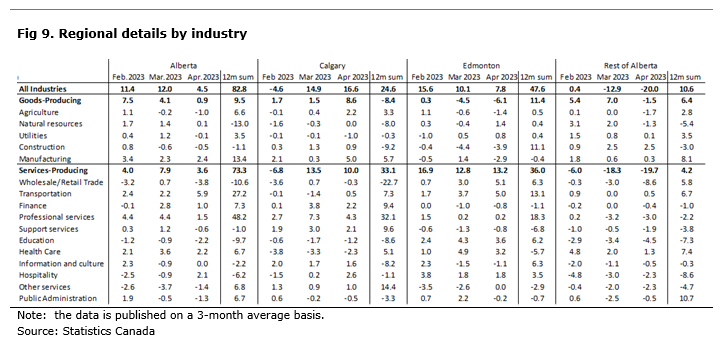

The job losses in Alberta were mainly in the service sector (-6.0k), while there were modest gains in the goods-producing sector (+4.1k). The gains in the goods-producing industry was concentrated in construction (+4.5k) and manufacturing (+1.5k), while there was a loss in natural resources (-1.1k).

The decline in the service sector was mainly in business, building and other support (-7.2k), trade(-4.1), finance, insurance and real estate (-3.8k), and education (-3.3k). These losses were partly offset by gains in accommodation and food services (+6.2k), other services (+2.2k), and information, culture and recreation (+1.6k).

Despite the overall employment being above its pre-COVID level by 6.1pp, only 10 out of 16 industries have a level of employment above their pre-pandemic levels. The lagging industries are: agriculture, natural resources, utilities, information, culture and recreation, accommodation and food services, and other services. Employment in the accommodation and food services sector, the worst-hit industry, remains more than 10% below its pre-COVID-19 level, underperforming the rest of the country.

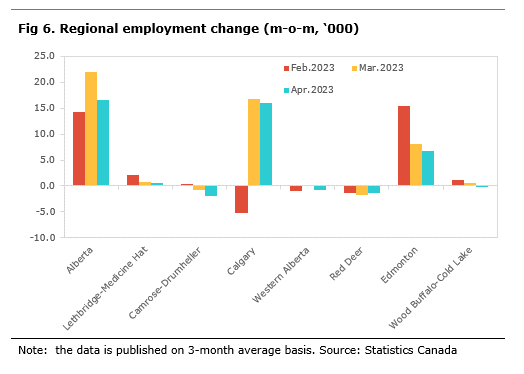

On a regional basis[1], the data is published on a three-month average basis (see table below). Over the past three months, the province gained 16.6k jobs each month on average. Most of the gains were in Calgary (+16.6k) and Edmonton (+6.6k). Conversely, there were declines in Camrose-Drumheller (-2.0k) and Red Deer (-1.4k). We note that this is the fourth consecutive decline in employment for Red Deer.

Over the past twelve months, employment in the province increased 84.4k, led by Edmonton (+44.4k), Calgary (+24.5k) and Camrose-Drumheller (+13.3k). All the other regions saw only marginal gains over the period.

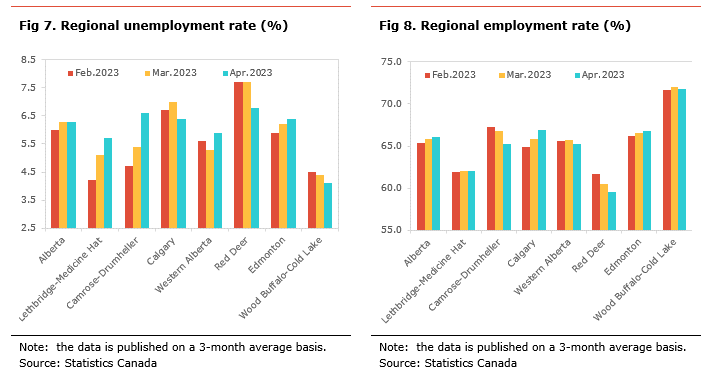

The unemployment rate for the province was unchanged at 6.3%, but the performance was mixed at the regional level. The unemployment rate increased in Camrose-Drumheller (+1.2pp), Lethbridge-Medicine Hat (+0.6pp), Western Alberta (+0.6pp), and Edmonton (+0.2pp). Conversely, the unemployment rate declined in Red Deer (-0.9pp), Calgary (-0.6pp), and Wood Buffalo-Cold Lake (-0.2pp).

The unemployment rate is the highest in Red Deer (+6.8%), Camrose-Drumheller (6.6%), Calgary (+6.4%) and Edmonton (6.4%). It is the lowest in Wood Buffalo-Cold Lake (4.1%), Lethbridge-Medicine Hat (5.7%), and Western Alberta (5.9%).

The employment rate for Alberta rose to 61.1% from 65.8%. The employment rate increased the most in Calgary (+1.0pp) and Edmonton (+0.2pp). It decreased in Camrose-Drumheller (-1.6pp), Red Deer (-1.1pp), and Western Alberta (-0.5pp).

[1] All the numbers are expressed as three-month average of the non-seasonally adjusted number.

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.