Economic insights provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Key takeaways:

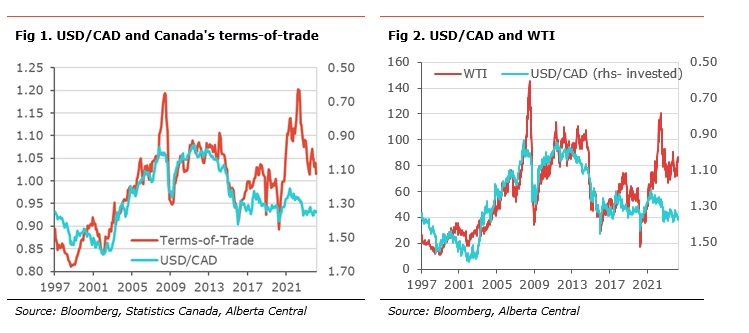

- Generally, an improvement in the terms-of-trade is linked to an appreciation of a country’s currency. In Canada, since commodity prices, especially oil, are a significant determinant of the change in our country’s terms-of-trade, it’s an important driver of the Canadian dollar (CAD).

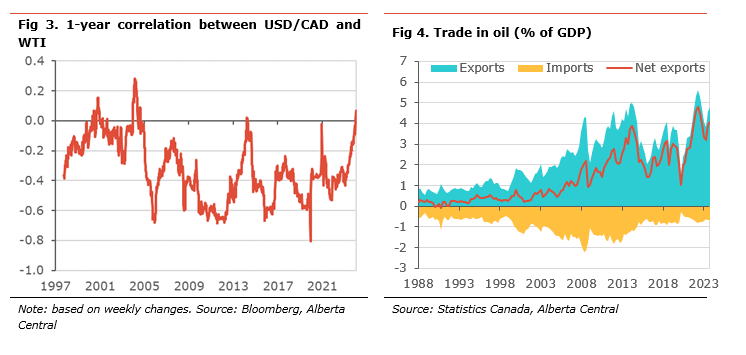

- However, it has been noted that the link between oil prices and the Canadian dollar seems to have diminished in recent years. As such, we note that the 1-year correlation between changes in the Western Texas Intermediate (WTI) and USD/CAD has turned positive; higher oil prices are associated with a depreciating CAD.

- Similarly, using an economic model of the changes in USD/CAD, we found that the coefficient associated with energy prices becomes not significant after 2017.

- While compelling and intuitive, the theory that links the terms-of-trade and the exchange rate has some practical flaws as it does not consider whether there is a foreign exchange flow; i.e., whether USD revenues are converted into CAD cash.

- As previously documented (see Where’s the boom? How the impact of oil on Alberta may have permanently weakened), while oil exports are close to record level, a smaller share of these revenues are returning to the Canadian economies. Hence, the impact of the positive terms-of-trade associated with higher oil prices is smaller than in previous episodes.

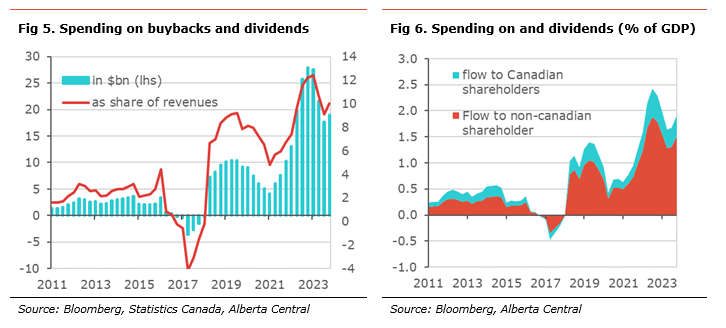

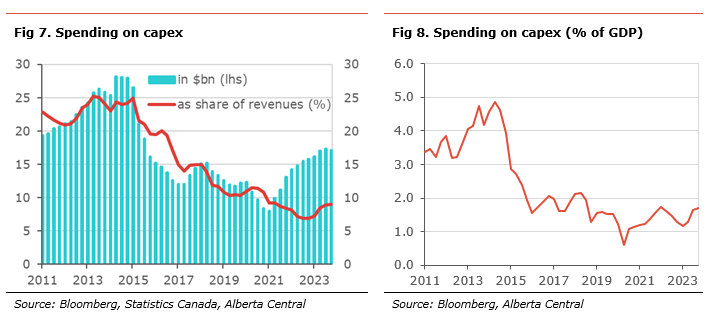

- More precisely, a greater share of revenues is being returned to shareholders, most of whom are not Canadian. Moreover, as a smaller share of oil revenues is being invested back into operations, a smaller share of oil producers’ cash is being converted into Canadian dollars.

- As a result, higher energy prices will have a greater impact on inflation due to the absence of currency appreciation, which previously provided a hedge.

- The smaller share of oil revenues returning to Canada means that the improvement in the terms-of-trade, due to higher oil prices, will have less of a positive impact on national income and growth, leading to less wealth created in the economy as oil prices increase.

- This could have potential implications for monetary policy, as higher oil prices will be more of a negative supply shock to the economy than previously.

The Canadian dollar (CAD) is viewed as a commodity currency; meaning that changes in commodity prices will affect its value. This fact has been well documented by decades of research at the Bank of Canada with commodity prices, often separated between energy and non-energy commodities, holding a key role in the BoC’s exchange rate models.

Similarly, financial market participants often simplify the relationship between CAD and commodity prices by looking primarily at the price of oil as one of the key determinants of the value of CAD. However, it was noted that the relationship between the Canadian dollar and oil prices has weakened in recent years.

In this report, we look at the diminishing influence of oil prices on the value of CAD and propose a compelling explanation for the diminished relationship.

The terms-of trade and the Canadian dollar: a broken relation

The terms-of-trade is the relative level between export prices and import prices. When export prices increase quicker than import prices, the terms of trade improve. This means that revenues for exporters increase faster than the costs for importers, all else equal. Consequently, there should be an increase in net inflows into the country. As more foreign currency needs to be converted into local currency, this leads to an appreciation of the local currency.

Canada is a prominent exporter of natural resources, with commodity exports representing about 45% of total Canadian exports of goods and services or a little more than 15% of GDP. This means that commodity prices heavily influence its terms-of-trade and the value of its currency. Similarly, oil has become an increasingly important commodity export in recent decades, with oil exports representing almost 5% of GDP (4% if looking at net exports) compared to less than 1% of GDP pre-2000s.

Hence, oil prices play an important role in the evolution of Canada’s terms-of-trade and on the Canadian dollar; this has been documented by the BoC (see The Turning Black Tide: Energy Prices and the Canadian Dollar). Moreover, financial market participants tend to focus on oil prices (mainly WTI) as a proxy for changes in the Canadian terms-of-trade and the exchange rate between the Canadian dollar and the US dollar, USD/CAD[1].

However, there seems to have been a break in the relationship between the Canadian dollar and oil prices (see chart above). Historically, both moved closely to each other. However, since 2022, while oil prices have increased sharply following the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, CAD has not appreciated similarly. In addition, the gap between the level of oil prices and USD/CAD has been persistent and does not show signs of narrowing. As such, we note that the correlation between USD/CAD and the Western Texas Intermediate (WTI) has diminished substantially over the period. While the 1-year correlation between weekly changes in WTI and USD/CAD has been about 0.4 on average since 2005, it has declined over the past year; now, it is slightly positive. This means that, over the past year, an increase in oil prices has been associated with an increase in USD/CAD or a depreciation in the Canadian dollar.

Pushing further the analysis using econometric modelling (see appendix for detailed results), we find that there has been a break in the relationship between USD/CAD and energy prices that occurred in the mid 2010s. As such, when regressing changes in the exchange rate on changes in energy commodity prices, changes in non-energy commodity prices, changes in the interest rate differential and the lagged independent variable, we find that from 1997 to 2014, the coefficient associated with energy commodity prices is significant and of anticipated sign; i.e., higher energy prices lead to an appreciation in the Canadian dollar. However, from 2016 to 2024, the coefficient becomes non-significant. This suggests that changes in energy prices are no longer a determinant of the changes in the Canadian dollar exchange rate.

Interestingly, our regression analysis shows that the importance of other factors influencing the Canadian dollar exchange change rate (such as non-energy commodity prices, interest rates differential, risk appetite) has not increased as the influence of energy prices has not become significant.

Why are oil prices no longer influencing the Canadian dollar?

While compelling and intuitive, the theory that links the terms-of-trade and the exchange rate has some flaws in practice. The main reason is that, while changes in commodity prices provided a good proxy for the foreign exchange flows involved, the actual amount of cash converted from US dollar to Canadian dollar may differ. The actual size of this transaction will determine the change in the exchange rate, not the evolution of export and import prices.

Such episodes have happened in the past. In February 2012, noting that the relationship between the Canadian dollar and WTI oil prices seemed to have broken, I was able to identify the widening spread between the Western Canada Select (WCS) and the WTI as a potential culprit.[2] The reason for the reduced link between USD/CAD and WTI is that the actual value of Canadian oil exports is smaller than estimated using only WTI; this is because of the discounted price Canadian oil producers receive for their oil, which is based on WCS. As a result, the potential flow into the Canadian dollar was smaller by about $2bn per month, according to our estimates, leading to less appreciation in the Canadian dollar.

A similar situation is occurring in recent years. However, the size of the flow being impacted is more sizeable, leading to a bigger impact on the relationship between CAD and oil prices.

With oil reaching record volumes and high prices, the value of Canadian oil exports reached a record of almost $150bn in 2022 and only declined modestly to about $125bn in 2023 – about a third higher than the peak reached in 2014. As a result, oil producers’ revenues remain close to their all-time highs at almost $200bn over the past year.

However, as we have documented (see Where’s the boom? How the impact of oil on Alberta may have permanently weakened), a smaller share of these revenues is returning to the Canadian and Albertan economies. Hence, the impact of the positive terms-of-trade associated with higher oil prices is smaller than in previous episodes. There are two reasons for this situation:[3]

- A greater share of revenues is being returned to shareholders. We estimate that about 10% of revenues (almost $20bn over the past year) are returned to shareholders through share buybacks and dividends. In comparison, that proportion was about 3% of revenues ($3.7bn) in 2014. Moreover, it is estimated that about 78% of these shareholders are non-Canadian, compared to 62% in 2014. This means that most of the flows back to shareholders is not an inflow into Canada. Adjusting for foreign ownership, we estimate that the payment to foreign shareholders is currently equivalent to about $11bn, or 1.5% of GDP, compared to about $3bn or 0.4% of GDP in 2014; almost four times bigger.

- A smaller share of revenues is invested back into operations. Most oil producers’ cash is likely held in USD. This is because, since oil is transacted in USD, most of their revenues are in this currency. In addition, we note that as about 75% of their financial market debt is issued in USD, USD cash is required for debt-service payments. As such, only the revenues converted into CAD to pay for expenses in Canada will affect the exchange rate. These expenses include operational costs in Canada and investment into Canadian operations.

As we have documented, oil producers are reinvesting a much smaller share of their revenues into their operations, most of which are in Canada. We estimate that they reinvested about 9% of their revenues (about $17bn) over the past year. This compares to about 25% of revenues in 2014 (about $28bn). Putting these flows into perspective, this estimated repatriation flow was almost $25bn, the equivalent of 5% of GDP, in 2014, while it is now about $12bn or 1.7% of GDP. This means the purchase of CAD for reinvestment is about half of what it used to be.

What is clear from these calculations is that the inflow into CAD from higher oil exports has most likely declined significantly compared to 2014. As a result, the appreciating pressures on CAD are much smaller.

Implications of a weaker link between CAD and oil prices

The lack of a relationship between oil prices and CAD will have broader implications for the Canadian economy. These include:

- Higher energy prices will have more impact on inflation than previously. This is because, as commodities are priced and paid in USD, when CAD appreciates with higher oil prices, the cost in Canadian dollars increases by less. However, without this exchange rate adjustment, more of the rise in commodity prices will pass through to inflation.

- The smaller share of oil revenues returning to Canada means that the improvement in the terms-of-trade is not as beneficial as suggested by export and import prices. As such, higher oil prices will have less of a positive impact on national income and growth, leading to less wealth created in the economy as oil prices increase.

In general, higher oil prices remain a net benefit to the Canadian economy. However, their impact is less positive than it was a decade ago.

This could have some potential implications for monetary policy, as higher oil prices will be more of a negative supply shock to the economy than they were previously. This implies that higher oil prices will be, in general, more inflationary and could lead to the BoC being more sensitive to energy prices when setting monetary policy. This is also important as the second-round effect from higher energy prices on other prices can be important in the Canadian context (see The current energy shock is more inflationary and stickier than the 1970s oil shocks).

Conclusion

The decline in the relationship between oil prices and the value of the Canadian dollar is a sign that higher oil prices are not leading to the same improvement in the terms-of-trade as in the mid-2010s. This means that the Canadian economy is less positively affected by an increase in energy prices because higher revenues are not fully flowing back into the country. This will lead to less improvement in national income and economic growth, making growth less sensitive to energy prices while being slightly more inflationary.

[1] In this report, we use financial market convention of expressing the exchange rate between the Canadian dollar and the US dollar as the number of Canadian dollars equivalent to one US dollar, denoted USD/CAD.

[2] See “Exploring the broken link between USD/CAD and oil prices”, Nomura Securities, 29 February 2012.

[3] Using available financial data from some of the big oil producers in Alberta, namely Suncor, Cenovus, Canadian Natural Resources, Imperial Oil, and Meg Energy.

Looking for more ? Subscribe now to receive Economic updates right to your inbox here!

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.