Economic commentary provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Key takeaways:

- At its latest monetary policy meeting, the Bank of Canada (BoC) kept its policy rate unchanged, but made it relatively clear that it is not yet ready to consider cutting interest rates.

- Many factors influence the BoC’s decision-making process and how the central bank thinks about the evolution of inflation.

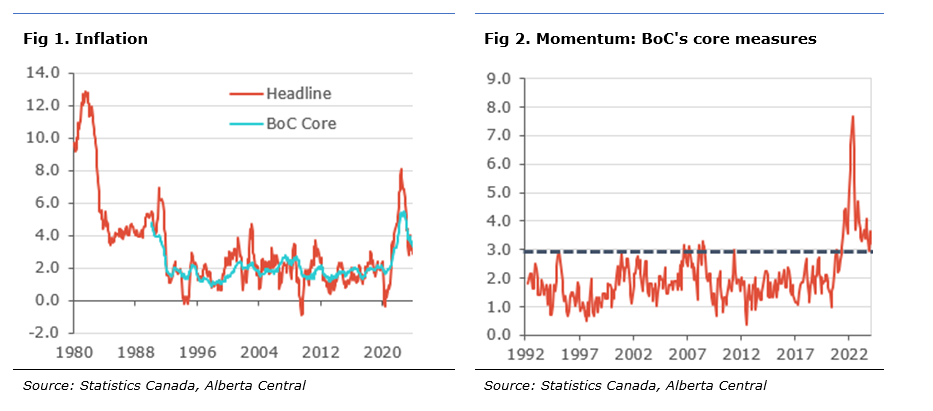

- While headline inflation is now within the target band of 1% to 3%, the BoC’s preferred measures of inflation remain above 3%. Moreover, their recent dynamics or momentums also remain above 3%.

- Our view is that the BoC is unlikely to consider cutting rates until the momentum measure for the preferred core measure returns sustainably well below 3%, meaning that its preferred measures of core inflation are below 3% and that their momentum is around or below 2.5%.

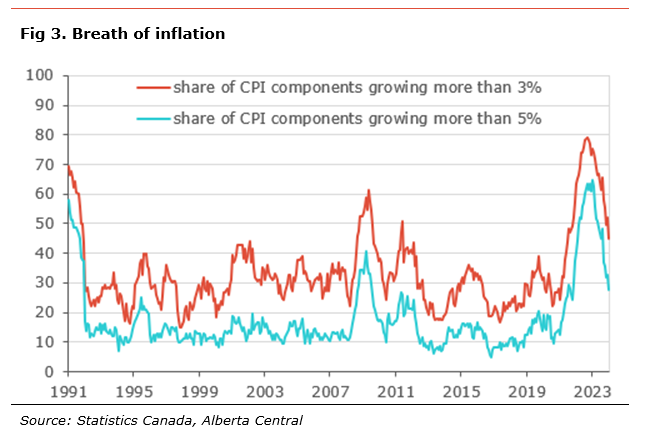

- The breadth of inflation also matters. While the shelter component is the main source of inflation, looking at all the components that compose the CPI basket, almost half of CPI components are rising above 3%, and more than a quarter are rising by more than 5%. These are well above where they were pre-pandemic.

- Inflation expectations matter because it can lead to persistence in inflation, especially if they are backward-looking. The most recent survey by the BoC shows that perceived inflation and the one-year and two-year ahead inflation expectations are all above current inflation. In addition, continued high inflation in an important component of CPI that is widely consumed by households, such as shelter, could be keeping inflation expectations high, easing inflation pressures in other sectors.

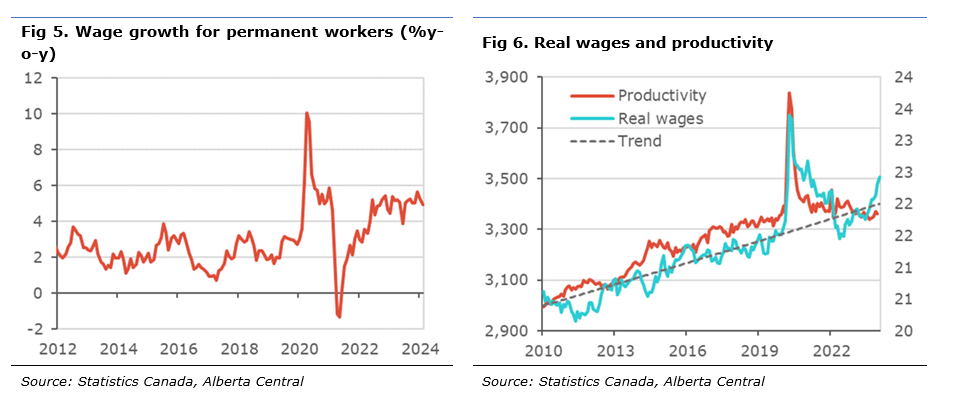

- Wage growth remains higher than the level consistent with inflation at 2% and well above the pre-pandemic level. While some of the increases in real wages can be attributed to a correction in purchasing power following the impact of high inflation, the increase over the past few months has diverged from its trend and productivity growth, pointing to higher unit labour costs. The higher costs for businesses may be passed on to consumers, leading to some persistence in inflation.

- Financial conditions have eased since last Fall, with the 5-year swap rate and corporate bond yields easing significantly. This has slightly lowered borrowing costs for consumers and businesses, making monetary conditions less restrictive.

- The neutral rate is likely higher than the BoC’s latest estimate, around 3.5%, supported by strong population growth in Canada and a global rise in neutral rates. This means that monetary policy may not be as restrictive as some may think. Moreover, this could also mean that the consensus likely underestimates the terminal rate of the upcoming monetary easing.

- Due to high prices, housing affordability is very sensitive to changes in interest rates. Recent activity in the housing market suggests significant pent-up demand that looks ready to be unleashed as interest rates decline.

- The BoC is likely concerned that easing monetary policy will lead to a sharp rise in housing demand when supply remains extremely low. The impact on house prices could be significant, leading to an exacerbated deterioration in affordability. The central bank would be blamed for a sharp appreciation of house prices and further deterioration in affordability.

- Insolvencies have been increasing fast, and many commentators have suggested that the BoC should cut rates before more borrowers become insolvent. While their call for lower interest rates is understandable, the BoC’s mandate is price stability, not bailing out borrowers who over-leveraged themselves when interest rates were low and can no longer make their payments now that interest rates have normalized. The BoC will only act if the rise in insolvencies is seen as leading to weaker growth and increased slack in the economy, which would risk pushing inflation too low.

- All in all, the BoC remains primarily focused on the inflation outlook when making its monetary decisions. As such, the evolution of inflation, growth and the labour market will dictate the pace of the monetary easing.

At its latest monetary policy meeting, the Bank of Canada (BoC) kept its policy rate unchanged and provided little guidance on the timing of a potential interest rate cut. However, their policy statement made it clear that the central bank is not yet ready to consider cutting interest rates.

There are a lot of factors influencing monetary policy and elements that the BoC considers when making policy decisions. In this report, we provide our views and thoughts on various topics and how they affect the BoC’s thinking of monetary policy.

Inflation outlook and recent dynamic

The BoC mandate is to maintain price stability. This is defined by its inflation target, which is to keep inflation between 1% to 3% with an aim for the 2% midpoint. As a result, inflation is one of the most important factors influencing monetary policy.

With this in mind, the inflation dynamic and timing to return to 2% matter greatly. The issue with the inflation rate is that it looks at the 12-month change in prices. However, the recent dynamic, i.e. the change in prices in recent months, is more important to the near-term inflation outlook. Hence, our team and the BoC have been focusing on the inflation momentum for some time, as defined as the 3-month change annualized in CPI.

The momentum in headline inflation is below 3%, suggesting that if the recent price dynamic continues for a year, the inflation rate will be below 3%; this falls within the inflation target band. Similarly, many measures of core inflation, including CPI excluding food and energy and CPI excluding the eight most volatile CPI components and the effect of indirect rates (the BoC’s previous preferred measure of core inflation), also have a momentum below 3%.

However, the momentum in the BoC’s preferred measures of core inflation, CPI-Trim and CPI-Median, remains above 3%, at 3.2% on average. Interestingly, when looking at the momentum of these measures, there seems to be a level shift that occurred during the pandemic. Before the pandemic, the momentum was mostly contained between 1% and 3%, the operational band of the inflation target. However, since mid-2021, the momentum measure has been persistently above 3%, the upper band of the inflation target.

Our view is that the BoC is unlikely to consider cutting rates until the momentum measure for the preferred core measure returns sustainably well below 3%. In our view, this likely means that the following two requirements must be met: 1) its preferred measures of core inflation are below 3%, and 2) their momentums are around or below 2.5%.

According to our latest inflation forecast, we do not expect both conditions to be met until April or May 2024. However, it is important to keep in mind the delay in the publication of CPI numbers. By the April meeting, the BoC will know CPI up to February. By the June meeting, the central bank will have inflation figures up to April and by July’s meeting, the CPI up to June will be available.

With this information in mind, the June meeting is likely the earliest the BoC will feel comfortable that its preferred measures of core inflation are sustainably below 3%. However, an upside inflation surprise in the coming months could very likely push the timing of the first rate cut to July, while the likelihood of a cut in April is very low, in our view.

Breadth of inflationary pressures

While the measures for headline and core inflation are more important, the breadth of the inflation process also matters. In other words, is inflation being driven by only a small subset of components, or are the upside pressures on inflation broad-based? This is an important distinction because in the former case, high inflation could be dismissed as only due to special factors. In contrast, in the latter case, high inflation is the result of pressures on a wide variety of prices.

In recent months, many analysts have focused on the fact that the shelter component of CPI has been the main source of inflation, contributing 1.8 percentage points to inflation in January. Shelter is the most important component of the CPI and represents almost 30%; this is more than 17% for food and 16% for transportation. As such, many have been focusing on the inflation in CPI excluding shelter, which is at 1.6%, as evidence that inflation is well within target and the BoC shouldn’t be worried.

While the shelter component is the main source of inflation, looking at all the components that compose the CPI basket, almost half of the CPI components are rising above 3%, and more than a quarter are rising by more than 5%. Moreover, both proportions are well above the norm that has prevailed since the inflation-target was adopted.

This situation shows that, despite a significant reduction in the breadth of the inflation process, there are still heightened inflationary pressures on a broad set of prices in the economy; as a result, focusing solely on shelter could be missing this point. Judging by the latest comments from the BoC, further progress toward more normal levels would be needed before cutting interest rates.

Expectations channel

Inflation expectations matter a lot for the inflation dynamic. The simplest model of inflation can be formalized as follows:

![]()

Where inflation today is equal to inflation expectations plus the inflationary pressures coming from the amount of excess demand or slack in the economy.

It is important to consider how agents form their inflation expectations. Some will be perfectly forward-looking and will look at current economic conditions to make their estimate. However, for many economic agents, it is much easier to look at where inflation is currently and assume that it will stay there. The greater the proportion of agents that rely on backward-looking inflation expectations, the more inflation will be persistent and depend on its current value. Most models of inflation used by the BoC incorporate a blend of forward and backward-looking inflation expectations.

So far, while long-term measures of inflation expectations have remained low and within the BoC’s inflation target, according to the BoC’s Survey of Consumer Expectations, one-year and two-years ahead inflation expectations remain well above their pre-pandemic levels and above the current inflation rate, at 4.9% and 3.9%, respectively. Moreover, these measures of inflation expectations have stabilized in recent quarters above the current level of inflation, suggesting no further reduction in expectations in recent quarters. In addition to expectations, perceived inflation is also above the current inflation rate at 5.9%.

Inflation expectations could also be impacted by price dynamics in some sectors. The high level of shelter costs inflation could be preventing inflation expectations from moderating. As mentioned previously, it is the most important component in the CPI basket. Moreover, both renters and homeowners are seeing fast-rising shelter costs. Since it is a big part of the consumption basket and consumed by all households, it is likely that its evolution has a much bigger impact on inflation expectations than other components (The same goes for food prices). Hence, while inflation excluding shelter is within the BoC’s target range, the fact that shelter costs are one of the fastest-rising components of CPI could push inflation expectations higher.

The lack of progress in returning inflation expectations to a level closer to the inflation target could be holding back the BoC from cutting rates. As we have shown with the simple model of inflation, if inflation expectations remain above target, it will mean persistently higher inflation and will require a bigger excess supply to bring inflation back to target. This suggests that the BoC should ensure that inflation is sustainably within the target band, i.e. below 3%, before cutting its policy rate.

There is also a risk that, by cutting too early and inflation picks up or if inflation proves to be more persistent than expected, there could be a cost to the BoC’s credibility as the central bank could be forced to reverse course. Moreover, if the situation increases inflation expectations, it could require more excess supply in the economy to bring inflation down.

Wage growth

High wage growth is another source of concern for the BoC. Similar to the BoC’s measure of core inflation, wage growth seems to have experienced a level shift higher in the post-pandemic era. Pre-COVID, average wage growth for permanent workers grew by 2.3% on average, while it has been mostly stuck around 5% since mid-2022.

As we wrote in the past (see here), high wage growth is inflationary via two channels: the demand side of the economy and the supply side. In the first instance, higher wages improve households’ purchasing power, supporting an increase in demand, which exacerbates inflationary pressures.

The second channel is how higher wages lead to an inflationary supply shock. Rapid wage growth, not supported by productivity gains and/or adjustments for the cost of living, increases business costs. The higher input cost will likely be passed on to consumers through higher prices, with business surveys showing that rising wages are a significant concern for most companies. The transfer of higher input costs to consumers, which contributes to higher inflation, prompts consumers to demand compensation for the higher cost of living; this, in turn, increases business costs, perpetuating an inflationary cycle. This inflationary loop is what the Bank of Canada is hoping to avoid by trying to contain wage growth. This is especially an issue if persistently high inflation leads to rising inflation expectations, making it more difficult to bring inflation back to target, as shown previously.

Looking at real wage growth and its trend since 2010, the current episode of high wage growth can be split into two periods. Before the pandemic, real wages increased at a rate compatible with productivity gains. From mid-2022 to mid-2023, real wages have been playing catch-up to its pre-pandemic trend, meaning that the strong wage growth was mainly to restore workers’ purchasing power that was affected by high inflation. Moreover, this was also supported by real wages returning to a level more consistent with labour productivity. However, since mid-2023, the level of real wages has been above its trend and has clearly decoupled from productivity.

This evidence suggests that wage growth since 2023 is leading to a rise in unit labour costs and is no longer supported by a catch-up in purchasing power. This is an inflationary combo, as businesses will likely need to pass the higher input costs to consumers to maintain their profit margins.

Financial conditions

As important as the policy rate is to the economy, various financial market rates influence or provide indications about the lending conditions to households and businesses.

On the consumer side, fixed mortgage rates closely follow swap rates. As such, there is a strong relationship between the Canadian 5-year swap rates and 5-year fixed mortgage rates. The swap rate increased by almost 100bp in the second half of 2023, reaching a peak of about 4.5% at the end of October, its highest level since late 2007. The swap rate has since dropped, reaching about 3.10% at the end of 2023 and is currently around 3.40%, providing some modest relief to borrowers. Nevertheless, swap rates remain at a level not seen since 2008.

The same kind of pattern is also observed in corporate bond yields. Using the Bloomberg Canada Aggregate corporate bond index, corporate bond yields have declined by almost 120bp since reaching a peak in October last year. Moreover, the spread compared to government yields has also narrowed by 50bp. Both suggest an easing in financial conditions for businesses over that period. Nevertheless, both the level of yields and the spreads remain elevated.

The easing of financial conditions for both consumers and businesses means that monetary policy is slightly less restrictive than it was in the Fall of last year, even though the Bank of Canada has kept its policy rate unchanged. This easing in financial conditions somewhat reduces the pressure on the BoC to lower interest rates.

Higher neutral rates

The BoC defines the neutral rate as “the policy rate consistent with output at its potential level and inflation equal to the target after the effects of all cyclical shocks have dissipated the level of interest rate”. This means that when the policy rate is below the neutral rate, monetary policy is accommodative, while it is restrictive when it is above the neutral rate.

As we have discussed in a piece last year (see here), the monetary policy stance matters; more precisely, whether monetary policy is restrictive or accommodative and by how much. The BoC’s current estimate of the neutral policy rate is between 2% and 3%. However, as Gov. Macklem admitted recently, “there are a number of things suggesting that the neutral rate could be higher,” hinting that the BoC’s estimate of the neutral rate is likely to be revised higher.

The factors that suggest a higher neutral rate are:

- A possible rise in the global neutral rate.

- The strong increase in population growth and its impact on labour input.

On the flip side, the Canadian productivity underperformance of late likely somewhat mitigated some of the neutral rate increase.

Considering all these factors, it is very likely that the neutral rate is higher, likely around 3.5% in our view. This means that monetary policy is less restrictive than some may think. This could partly explain why, despite the sharp monetary tightening since 2022, the economy has remained relatively resilient and has not experienced a recession.

One consequence of a higher neutral rate is not so much on the timing of when the BoC decides to cut rates, as there is little doubt that monetary policy is currently in restrictive territory; rather, the main impact is at what level of interest rates will the BoC stop cutting. Currently, the consensus expects the policy rate to reach 3.00% by the end of 2025. However, this could be too low if the neutral rate is indeed higher.

Another consequence of a higher neutral rate will be that interest rates will most likely be higher in the coming years than during the decade that preceded the pandemic. Gov. Macklem pointed to this possibility, saying “Whether you are a bank or business or government or household, I don’t think you should expect interest rates to go back to pre-Covid levels, so there’s an adjustment to come.”

Housing market

In a previous piece, we have shown how interest rate changes significantly impact affordability (see here). This results from ballooning the size of the borrowing required to purchase the average house over the past two decades, leading to a heightened sensitivity to interest rates.

We can see some of this increased sensitivity to interest rates in recent years and months. It is no coincidence that activity in the housing market bounced back in late 2023 and early 2024. At the same time, we saw a decline in the 5-year swap rate, leading to lower mortgage rates.

This situation shows that small changes in interest rates can have a big impact on the housing market and that there is a tremendous pent-up demand waiting for lower interest rates to jump back into the housing market. The BoC is likely concerned that easing monetary policy will lead to a sharp rise in housing demand when supply remains extremely low. The impact on house prices could be significant, leading to an exacerbated deterioration in affordability.

While house prices are not directly part of the CPI, a sharp rise in house prices would filter through in the “homeowners’ replacement costs”. Moreover, a significant increase in house prices could also impact inflation expectations. This could lead to inflation being more persistent than initially expected.

The BoC is finding itself in a very difficult situation. It has been blamed for weak economic activity, lower house prices and declining affordability. However, if it cuts interest rates, it will be blamed for the sharp appreciation of house prices and the further deterioration in affordability.

Rising insolvencies

A consequence of the combination of record debt levels and higher interest rates after a prolonged period of very low interest rates is that we are witnessing a sharp rise in insolvencies over the past year (see here for the latest data). However, a resilient labour market has meant that the increase in insolvencies on the consumer side has mainly been in proposals (i.e. renegotiation of terms), not bankruptcies. Insolvencies will likely continue to rise in the coming months as more borrowers renew their lending at higher interest rates.

On the business side, the latest data shows a jump in bankruptcies to levels not seen since 2004. However, the data could be distorted by the CEBA loan repayments in January. Nevertheless, it remains clear that many businesses are facing financial difficulties.

Many commentators have suggested that the BoC should cut rates now before more borrowers become insolvent. While their call for lower interest rates is understandable, the BoC’s mandate is price stability, not preventing insolvencies. As harsh as it may sound, it is not the role of monetary policy to bail out borrowers who over-leveraged themselves when interest rates were low and can no longer make their payments now that interest rates have normalized. The BoC will only act if the rise in insolvencies is seen as leading to weaker growth and increased slack in the economy, which would push inflation too low.

A counterargument, however, could be that leaving rates too low for too long pre-covid and during the post-covid recovery could have had the unintended consequences of agents loading up on cheap debt. This is not to exclude the BoC’s messaging during the pandemic, which stated that interest rates were to stay very low for a long time. As this wasn’t the case, the BoC can be seen as somewhat responsible for the recent debt accumulation at very low interest rates.

Conclusion

All these factors will influence the BoC’s decision-making process in the coming months. Considering all this information, we believe that the BoC will cut its policy rate at the June meeting. However, as mentioned previously, the risk is that it could be delayed if inflation does not moderate as expected. Moreover, while we continue to believe that the BoC is likely to cut by 100bp by the end of 2024, there is a risk that the BoC could be less aggressive than expected and the total amount of cuts this year may be smaller. The evolution of inflation, the economy and the labour market will dictate the pace of the monetary easing (see here).

Looking for more ? Subscribe now to receive Economic updates right to your inbox here!

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.