Economic insight provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

*This report includes regional details for Alberta.

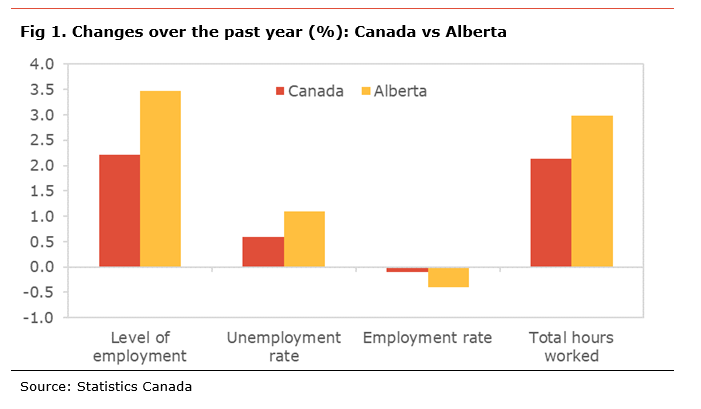

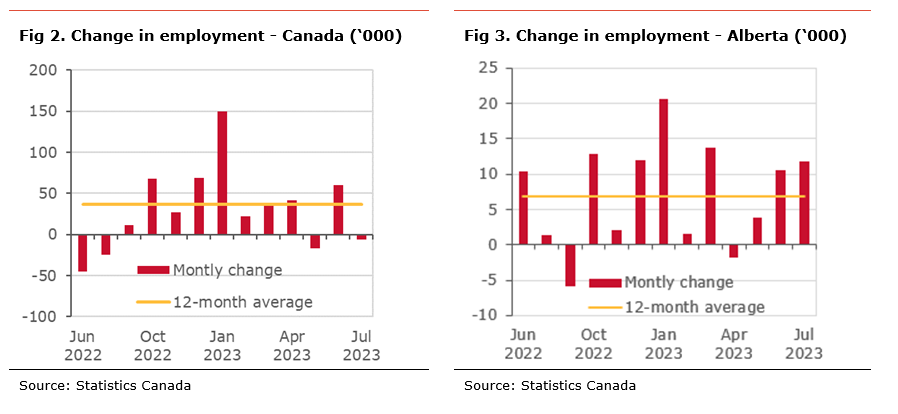

Bottom line: Today’s Labour Force Survey data points to some softening in the labour market in Canada, with a slowing pace of job gains in recent months resulting in a slight rise in the unemployment rate to 5.5%. Despite the higher unemployment rate, the labour market remains tight, something the Bank of Canada is closely monitoring.

However, the report also shows that wage growth rose to 5.0%. Moreover, we estimate that the 3-month annualized change of the seasonally-adjusted series jumped to 6.1%, suggesting a further acceleration in wage growth. While concerning the acceleration is mainly due to a sharp rise in July. Whether the pattern continues in August will matter.

The Bank of Canada will welcome an easing in the pace of job creation. As such, the higher unemployment rate, while still historically low, suggests some slack in the labour market is slowly being created. However, wage growth remains disconnected from weak labour productivity.

With some slack gradually being created and inflation expected to continue to moderate, albeit at a slow pace, we believe that the BoC will leave its policy rate unchanged for the rest of the year (see What happened to the recession? The role of the policy stance and demographic for our latest view on the economic outlook). However, the BoC made it clear that it will choose inflation in the tug-of-war between fighting inflation and avoiding a recession.

Alberta saw another robust increase in employment in July, but the unemployment rate rose to 6.1% as more workers entered the labour market. Over the past twelve months, the Alberta labour market has outperformed the rest of the country in terms of job gains. However, the unemployment rate in Alberta remains higher than the national measure, partly due to the strong population growth. After almost 3 years of underperformance, wage growth in Alberta (+5.1% y-o-y) was marginally higher than in the rest of Canada (5.0% y-o-y) for the first time since August 2020. It remains to be seen if it will be sustained (see Where’s the boom? And the rise and fall of the Alberta Advantage).

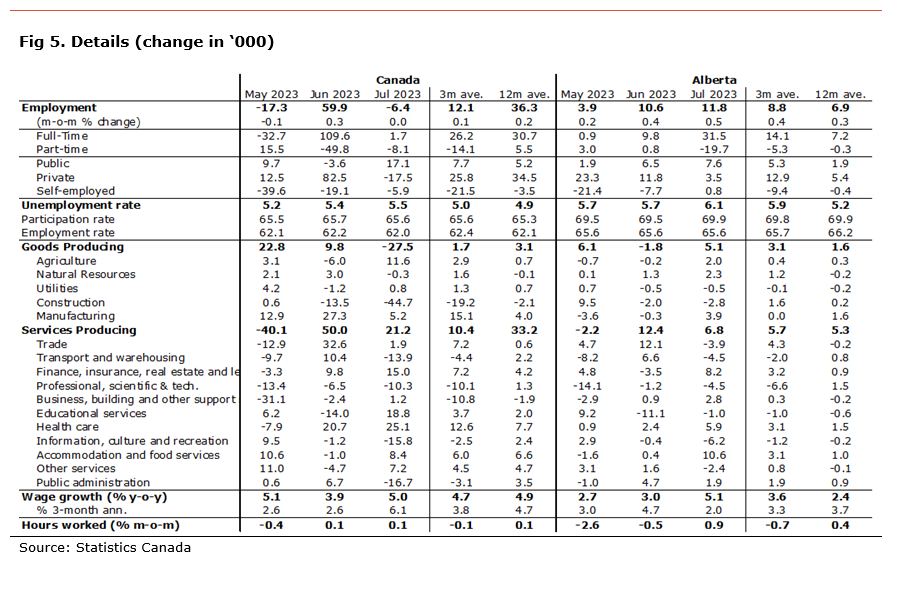

Employment eased by 6.4k in July, after a strong rise in June. With the weakness in employment, the unemployment rate rose to 5.5%, its highest level since January 2022 but still historically low. The higher unemployment rate was mainly due to the weak job gains, with the participation rate inching lower to 65.6% from 65.7%. The participation rate is only 0.3 percentage points (pp) lower than before the pandemic, as workers left the labour force. If the participation was the same as before the pandemic, the unemployment rate would be 5.9%. The employment rate, the share of the population holding a job, decreased to 62.0%, marginally below its pre-COVID level. Wage growth accelerated to 5.0% y-o-y. The 3-month annualized change in wages increased sharply to 6.1%, suggesting that wage growth accelerated rapidly.

The details show that the job losses in July were all part-time (-8.1k), while full-time jobs were little changed (+1.7k). In addition, the decrease in employment was mostly in the private sector (-17.5k), while there were also losses in self-employed (-5.9k) but gains the public sector (+17.1k).

On an industrial level, there was lower employment in the goods-producing sector (-27.5k) but gains in the service sector (+21.2k).

The details in the good-producing sector show that the job losses were mainly in construction (-44.7k), the second consecutive month of decline. This was partly offset by gains in agriculture (+11.6k) and manufacturing (+5.2k).

The gains in the service industry came mainly from health care (+25.1k), education (+18.8k), finance, insurance and real estate (+15.0k). and accommodation and food services (+8.4k). Losses in public administration (-16.7k), information, culture and recreation (-15.8k), transport and warehousing (-13.9k), and professional, scientific and technical (-10.3k) partly offset these gains.

Despite continuous gains in employment and the overall level of employment being above its pre-COVID level by 5.1 percentage points, only 11 out of 16 industries have a level of employment above its pre-pandemic level. The lagging sectors are: agriculture, transport and warehousing, business, building and other support services, accommodation and food services, and other services. Employment in the accommodation and food services is still about 7% below its pre-COVID-19 level, but continues to improve.

In Alberta, employment increased by 11.8k in July. Despite the robust employment gain, the unemployment rate rose to 6.1%, its highest since April 2022, due to a sharp increase in the participation rate to 69.9% from 69.5%. The participation rate in the province is still 1.2 percentage points (pp) below its pre-pandemic level suggesting many workers are remaining on the sidelines. If the participation rate was at the same level as before the pandemic, the unemployment rate in the province would be 7.7%. The employment rate, the share of the population holding a job, was also unchanged at 65.6%, slightly below its pre-pandemic level.

The job gains in Alberta were mainly in the public (+7.6k) and private sectors (+3.5k), while gains in self-employed were modest. Similarly, both the goods-producing sector (+5.1k) and the service sector (+6.8k) saw higher employment.

The increase in the goods-producing industry was in manufacturing (+3.9k), natural resources (+2.3k), and agriculture (+2.0k). These gains were partly offset by losses in construction (-2.8k) utilities (-0.5k).

The higher employment in the service sector was mainly in accommodation and food services (+10.6k), finance, insurance and real estate (+8.2k), and health care (+5.9k). Lower employment in information, culture and recreation (-6.2k), professional, scientific and technical (-4.5k), transport and warehousing (-4.5k), and trade (-3.9k) offset some of these gains.

Despite the overall employment being above its pre-COVID level by 6.7pp, only 9 out of 16 industries have a level of employment above their pre-pandemic levels. The lagging industries are: agriculture, natural resources, utilities, manufacturing, information, culture and recreation, accommodation and food services, and other services. Employment in the accommodation and food services sector, the worst-hit industry, remains more than 10% below its pre-COVID-19 level, underperforming the rest of the country.

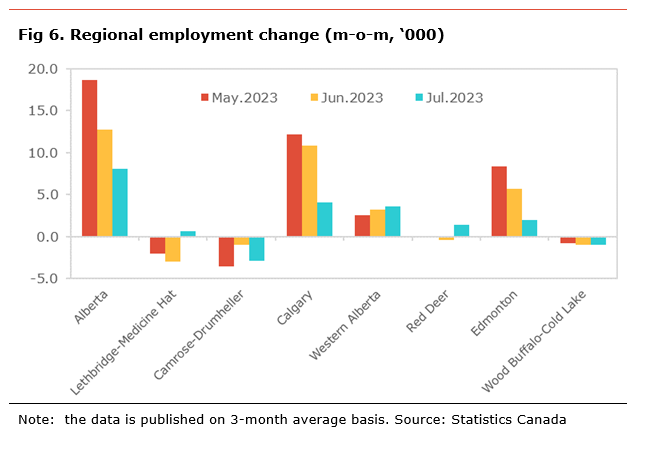

On a regional basis[1], the data is published on a three-month average basis (see table below). Over the past three months, the province gained 8.1k jobs each month on average. Most of the gains were in Calgary (+4.1k) and Western Alberta (+3.6k). Conversely, there were declines in Camrose-Drumheller (-2.9k) and Wood Buffalo-Cold Lake (-0.9k).

The unemployment rate for the province was unchanged at 5.8%. However, the performance was mixed at the regional level. The unemployment rate declined the most in Camrose-Drumheller (-1.5pp), Western Alberta (-0.2pp), Red Deer (-0.2pp) and Edmonton (-0.1pp), while it increased in Lethbridge-Medicine Hat (+0.5pp), Wood Buffalo-Cold Lake (+0.5pp), and Calgary (+0.3pp).

The unemployment rate is the highest in Calgary (6.1%), Lethbridge-Medicine Hat (5.9%), and Edmonton (+5.9%). It is the lowest in Camrose-Drumheller (3.8%), Western Alberta (5.1%), and Wood Buffalo-Cold Lake (5.2%)

The employment rate for Alberta was unchanged at 66.3%. The employment rate increased the most in Western Alberta (+0.9pp), and Red Deer (+0.5pp). It decreased in Camrose-Drumheller (-1.9pp), Wood Buffalo-Cold Lake (-1.1pp), and Edmonton (-0.2pp).

[1] All the numbers are expressed as three-month average of the non-seasonally adjusted number.

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.