Economic insight provided by Alberta Central Chief Economist Charles St-Arnaud.

Main takeaways

- The Canadian economy was expected to slow meaningfully in the first half of 2023 as a result of the sharply higher interest rates.

- A possible explanation for the resilience is that monetary policy remained accommodative for a long period of time after the start of the monetary tightening.

- The policy rate did not move above the neutral until Fall 2022, while the real policy rate did not turn positive until Spring 2023. This means that monetary policy was not convincingly restrictive until then.

- Looking at previous cycles, we find that, on average, it takes about 5 to 6 quarters after monetary policy move into restrictive territory before the economy goes into a downturn.

- These results suggest that the sharp slowdown of the economy is likely only delayed and should be expected to start in late 2023-early 2024.

- Another explanation for the resilience of the economy is the strong population growth which obscures underlying trend in the economy and pushes growth higher, proving a buffer against negative growth.

- For example, while consumer spending has continued to increase in aggregate, spending per capita has been stagnating since early 2022. The same trend is also seen in income.

- Using our findings, we update our outlook for the Canadian economy, with growth expected at 1.6% in 2023 and 0.8% in 2024. We continue to expect the economy to experience a soft landing, with most of the weaker growth happening in 2023Q4 and 2024Q1. But the risk of a recession remains elevated at 40%.

- Inflation is expected to remain above 3% until Spring 2024 and then very gradually moderate, reaching 2% only in 2025.

- As a result, we expect the Bank of Canada to leave its monetary policy rate unchanged until the end of 2024Q1 and to gradually ease throughout the year, with the policy rate ending 2024 at 3.5%.

- Alberta is expected to remain one of the fastest growing provinces with growth of 2.7% in 2023 and 1.8% in 2024. The economy will remain supported by strong population growth and continued elevated revenues in the oil sector, offsetting weakening consumer spending as a result of higher interest rates.

At the end of 2022, most forecasters expected the Canadian economy to stall or contract in the first half of 2023. However, with half of the year completed, the economy remains resilient and growth is likely to average about 2% over the period. The expectation was that the aggressive monetary tightening in 2022 should have led to a more significant slowdown of the economy, especially considering the amount of debt in the economy.

This situation raises an important question: is the Canadian economy less sensitive to interest rates than initially thought or are the interest rate hikes slower to affect the economy than initially thought?

The monetary policy stance matters

To fight inflation, the BoC has raised its policy rate by 475bp since the start of its tightening cycle in March 2022. The increase in interest rates was one of the fastest in Canadian history, with interest rates increasing by 425bp in less than a year. It is not just the rapid rate of hikes that made this tightening unique. It is the starting point for the policy rate at 0.25%, its lowest on record and well into the accommodative territory, making this cycle exceptional.

Given the high level of debt in the Canadian economy, especially household debt, the economy was expected to be particularly sensitive to a rise in interest rates. Against expectations, the Canadian economy has proven much more resilient, with growth remaining robust, supported by a strong labour market and buoyant consumer spending. It was expected that higher interest rates and the reduction in household purchasing power would have led to a weakening in consumer spending. The only sector to have had a significant slowdown due to the rise in interest rates has been the housing market. But, after a correction in 2022, the market is recovering as demand improves while supply remains weak.

The monetary policy stance

Looking at the situation ex-post, an important aspect of monetary policy seems to have been overlooked: the policy stance i.e. whether monetary policy is accommodative or restrictive.

The policy stance is an important concept because it measures the degree of support or restrain monetary policy is giving to the economy. Central banks have for a long time illustrated the impact of monetary policy using driving analogies.

- An accommodative policy is like stepping on the gas pedal. The further down it goes, the more the car will accelerate, i.e. the more policy is accommodative, the more support there is for the economy. Similarly, lifting your foot from the accelerator still provides power to the motor, just less. This is the same as when rates are increased and the policy stance becomes less accommodative. Monetary policy still stimulates the economy, just less than before.

- A restrictive monetary policy is equivalent to hitting the brake pedal. If the pedal is only lightly pressed, the deceleration is gentle. However, the harder the brake pedal is pressed, the faster the deceleration. Once monetary policy moves into restrictive territory, it will be a drag on the economy and force a deceleration. How restrictive monetary policy is will determine the amount of drag.

There are two main ways to evaluate whether monetary policy is restrictive or accommodative: real interest rates and deviations from the neutral rate.

Deviation from the neutral rate

The BoC defines the neutral rate as “the policy rate consistent with output at its potential level and inflation equal to the target after the effects of all cyclical shocks have dissipated the level of interest rate”. This means that when the policy rate is below the neutral rate, monetary policy is accommodative, while it is restrictive when it is above the neutral rate.

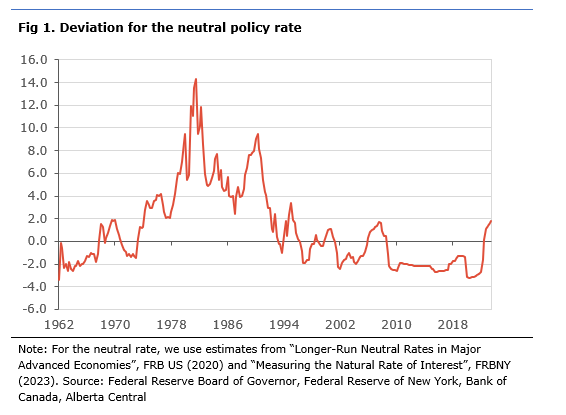

The BoC estimates the neutral policy rate to be between 2 and 3%. However, we would note that the population growth and higher neutral rate globally could suggest a higher neutral rate in Canada. Based on this estimate, the policy rate didn’t convincingly rise above the neutral rate until the Fall of 2022, when it reached 3.5% in September. As a result, it can be viewed that monetary policy was not restrictive until also the last quarter of 2022.

Real interest rates

The real interest rate, as measured by the nominal policy rate minus the rate of inflation, is the rate of interest an investor, savers or lenders receive (or expect to receive) after taking inflation into account. It can be another useful measure of whether monetary policy is accommodative or restrictive.

- A decline in the real interest rate means that the rate of return adjusted for inflation declined. This incentivizes agents to use their money now rather than save it and consume at a later date. This provides support for spending, both consumer spending and business investment, supporting growth.

- A rise in the real interest rate does the opposite. Increasing the rate of return on saving incentives agents to delay their spending, reducing economic activity.

This is important because a negative real interest rate means that the rate of return on investment does not compensate for inflation. In other words, a dollar today has more purchasing power than a dollar saved. As a result, despite the increase in the real interest rate, agents continue to be incentivized to use their money now rather than in the future, supporting spending and growth.

A delayed negative impact from monetary policy

The fact that monetary policy didn’t turn restrictive until late 2022 and that real interest rates remained negative until the beginning of the year could explain why the economy remained resilient so far this year. As mentioned, these observations mean that monetary policy was likely still accommodative, albeit mildly, and supporting growth.

There is also a question of the lags in monetary policy transmission. In other words, how long does it take for the higher interest rates and the restrictive monetary policy to impact growth?

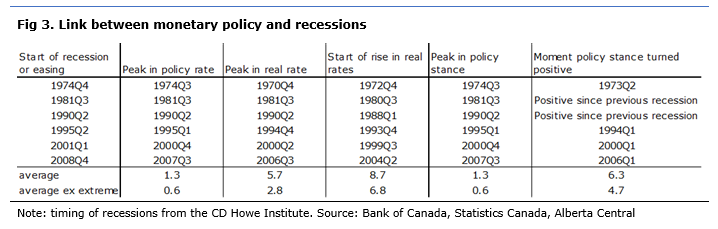

Looking at past recessions in Canada and adding periods of monetary tightening that led to some monetary easing without a downturn, more precisely 1995 and 2001, we look at what is the usual lag between the start of the recession or easing periods and: the peak in the policy rate, peak in real interest rates, the start of the rise in real rate, peak in the policy stance and the moment the policy stance turned positive. The table in Fig. 3 summarizes the findings.

Key observations:

- The policy rate tends to peak one quarter ahead of the downturn or on the same quarter.

- On average, the real interest rate peaks 6 quarters before the downturn. However, this result is heavily influenced by the 1974 recession, where it peaked 20 quarters before the recession. If we exclude this episode, the average is closer to 3 quarters.

- The downturn usually happens 9 quarters after real rates have started to rise. If we exclude the 2008Q4 recession, where the real rate increased for 18 months before the recession started, the average is 7 quarters.

- The policy stance usually peaks about one quarter before the recession happens.

- The policy stance tends to turn positive 6 quarters before the downturn. If we exclude the 2008 recession, the average is 5 quarters.

Using those historical patterns suggests that, with the policy rate having turned restrictive in 2022Q3, the downturn could start in 2023Q4 or 2024Q1. Using the evidence from the real rates, with real rates starting to increase in 2022Q2 it seems that the downturn could happen between 2024Q1 and 2024Q3.

These observations likely explain why we have not seen a downturn after the sharp increase in interest rates over the past year and a half.

However, there are many caveats. For example, during the 2008 recession, the delay between the policy stance turning restrictive, the rise in the real rate and the start of the downturn was much longer than in the previous episode. Moreover, the downturn was more the result of the financial crisis, which started in the US, than due to Canadian monetary policy. It raises the question of whether the Canadian economy could have had a soft landing during that episode if the financial crisis didn’t happen.

Strong population growth matters

Canada’s population grew by 3.1% y-o-y, its fastest pace since the early 1960s. The rapid rise in population significantly impacts the economy and is likely to reduce the risk of a recession.

Higher population growth leads to higher economic growth

This impact is simple mathematics. The growing population means that the pool of consumers also increases, leading to a rise in aggregate demand of about the same magnitude as population growth.

This higher growth rate reduces the risk of a recession because growth has more room to slow before turning negative. However, it still means that a period of weak growth will lead to a reduction in excess demand or a rise in excess supply.

Strong population growth hides softness in household spending

Consumer spending has been relatively robust since the BoC started tightening monetary policy last year. We expected that the combined impact of the decline in purchasing power due to the high inflation and the higher interest rates would have led to a moderation in consumer spending.

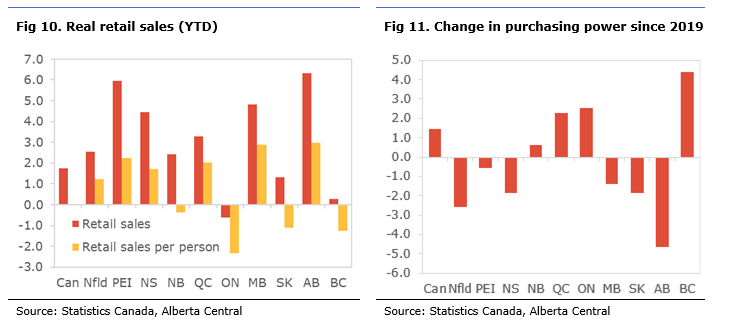

The issue is that the data focuses on aggregate spending, whether one looks at retail sales or at the consumer spending part of GDP. However, when we control for the strong population growth, we find that retail sales in volume per capita have been mostly unchanged since early 2022. As such, they have declined by about 0.1% year-to-date compared to an increase of 1.8% year-to-date for total retail sales in volume.

The slight decline in consumption per capita shows that the average consumer is likely reducing spending due to the decrease in purchasing power and higher interest rates. Strong population growth masks this trend because the number of consumers grows faster than the reduction in average consumption.

The strong population growth also hides other important trends. One of them is that household disposable income per household is stagnating. The same can also be said of GDP per capita. This suggests that the average household in Canada is not seeing an improvement in its income and wealth despite a growing economy. This could reinforce the decline in consumption per capita.

All put together, it is clear that strong population growth is an explanation of the resilience of the economy in recent quarters, reducing the likelihood of a recession.

Outlook revisions

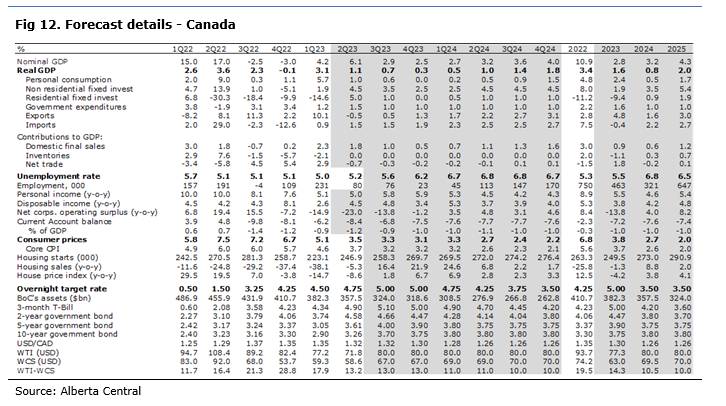

Using the information above, we take the opportunity to provide a forecast update for the rest of 2023 and 2024 (see Fig xxx for details). In general, our view hasn’t changed, and we believe the Canadian economy is likely to have a soft landing, i.e., a recession is not our base case. Nevertheless, the risk of a recession remains high at about 40%, albeit lower than the 50% thought at the beginning of the year. As mentioned earlier, strong population growth increases the economy’s growth rate, offering a buffer against economic contraction.

Growth

After being resilient in the first half of the year, growth is expected to slow. In line with our previous findings, the full impact of the monetary policy tightening should be felt in 2023Q4 and 2024Q1, with growth expected to stall during this period. Growth is also likely to be weak in 2023Q2 and 2023Q3, but some of the weakness will be due to the temporary impact of the federal public workers, the cut to oil production due to the forest fires in Alberta, and the strike at the port of Vancouver.

Growth should improve very gradually starting in 2024Q2. However, the acceleration will be slow, with the growth rate of the economy not expected to return above 2% until 2025. As a result, we currently expect growth to be 1.6% in 2023 and 0.8% in 2024.

With growth slowing in the coming quarters, we should see weakness in the labour market. As a result, job creation will weaken and not be high enough to absorb the strong flow of newcomers to the labour market, resulting in a rise in the unemployment rate, peaking at around 6.8% around the end of 2024.

Inflation

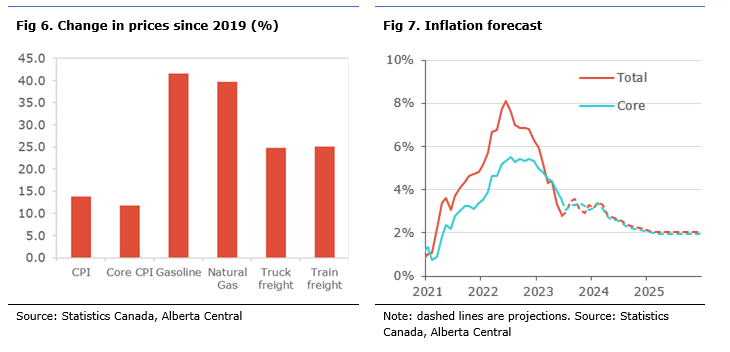

Inflation has decelerated sharply since the beginning of the year, from about 6% to 3% currently, roughly in line with our expectations. Most of the moderation comes from a base effect in energy prices, which are almost 15% below their 2022 levels. However, with gasoline prices currently above where they were in late 2023, energy prices will likely positively contribute to inflation in the coming months if prices remain at current levels.

Core measures of inflation have also decelerated to about 3%, their lowest since late 2021, and are proving stickier than the BoC expected. More specifically, the momentum in prices, as measured by the three-month annualized change in prices, remains consistent with inflation between 3.5% and 4%, depending on the measure of core inflation. This is still higher than the BoC’s objective of keeping inflation between 1% and 3%.

As we wrote previously (see The current energy shock is more inflationary and stickier than the 1970s oil shocks), the energy shock of 2022 resulted in the fastest and sharpest surge in gasoline prices in recent history. With energy costs still high, transportation costs, like freight costs by truck or trains, are still about 25% above their 2019 levels. In a vast country like Canada, where everything needs to be transported, transportation costs are a significant input cost for many businesses that will eventually be passed to consumers, explaining some of the stickiness in inflation.

Measures of core inflation are expected to continue to decelerate, especially later this year and earlier next year, as weak growth will reduce the amount of excess demand in the economy and inflationary pressures. Nevertheless, we expect core inflation to remain above 3% until 2024Q2 but will continue to gradually ease, reaching 2% at the beginning of 2025.

Policy rate

Based on the expectations of a soft landing for the economy and inflation remaining above 3%, the BoC is expected to keep its policy rate unchanged for the rest of 2023. However, weaker growth in late 2023 and early 2024, and inflation expected to ease below 3% in 2024Q2, will allow the BoC to ease monetary policy in early 2024.

We expect the first rate cut to happen late in the first quarter of 2024 and the policy rate will be gradually lowered throughout 2024 to end the year at 3.5%. We think the BoC will want to return the policy rate close to neutral gradually, likely easing by 25bp at each meeting until it reaches 3.50% in the fourth quarter.

The timing of the first rate cut and the pace of the subsequent easing will depend heavily on the outlook for inflation. We think the BoC will continue to prioritize inflation over growth or the labour market in 2024.

Outlook for Alberta

Alberta is expected to remain one of the fastest-growing provinces in Canada. Many factors will continue to support growth in the province, offsetting some of the headwinds caused by rising interest rates. As such, we expect the economy of the province to grow by 2.7% in 2023, after an estimated 5.2% in 2022, and to slow to 1.8% in 2024.

Strong population growth will provide sustained support to growth, with international and interprovincial migration remaining elevated, as many households are drawn to the province by the still affordable housing market. However, this population surge is likely to strain parts of the economy where supply is slower to adjust, especially housing and public services.

Energy

The energy sector will remain an important tailwind to the economy, with oil prices expected to remain around $80 a barrel. The decline in production due to the forest fires and its economic impact is significantly smaller than during the fires in Wood Buffalo in 2016 and will have only a marginal and temporary impact on the outlook.

Nevertheless, we do not expect oil producers to modify their behaviour (see Where’s the boom? How the impact of oil on Alberta may have permanently weakened) and continue to expect that only a modest share of income will be reinvested in the local economy. Nevertheless, investment in the sector is expected to continue to rise but remains well below the levels seen in the mid-2010s.

The continued robust oil price and substantial oil revenues will continue to support fiscal revenues. Moreover, the likely activation of the TransMountain pipeline in late 2023 should reduce the differential between the Western Canada Select and the West Texas Intermediate, leading to increased profitability and fiscal revenues from oil royalties.

Consumers

Strong retail sales since the beginning of the year, even adjusted for inflation and population, suggests that consumer spending remains solid and has generally been more robust than in other provinces. However, stronger retail sal odd with a bigger decline in purchasing power in Alberta than in the rest of Canada in recent years, as income and wages continue to underperform the rest of the country (see The Alberta Advantage is melting away and Where’s the boom? And the rise and fall of the Alberta Advantage.) The solid labour market is likely providing some support.

With the third highest debt-to-disposable income among provinces, after BC and Ontario, there is a risk that higher interest rates could have a bigger impact on Alberta than in the rest of the country. Already, insolvencies are above their pre-pandemic level, suggesting a rising proportion of households are under financial stress.

Like in the rest of Canada, we expect the province’s unemployment rate to rise to 6.8% in early 2024. This results from slower employment gains as the economy slows, which means that the labour market will not be able to absorb all the newcomers.

Agricultural sector

Continued drought conditions in many regions of the province have forced many local governments to declare an “agricultural disaster.” The lack of moisture is likely to mean much lower crop yields this year and a drag on growth. So far this year, farm receipts have remained elevated and are higher than last year, thanks to elevated prices for Alberta’s main crops. This situation could help mitigate the impact on farm revenues from weaker yields and a smaller harvest. Livestock producers are also under pressure, as the low moisture levels have devastated pastures. This could force beef producers to thin their heard.

Risks to the outlook

Downside: The strength of the labour market will be key for the outlook, as it has been a source of economic resilience. The situation could deteriorate rapidly if slower growth or a negative shock led to job losses. Given the level of debt, it is very likely that most households need two incomes to service their debt. This means that they are highly vulnerable to a decline in income following a job loss. Such a situation could have important spillovers on consumer spending, the housing market and financial institutions.

Upside: the economy could continue to prove more resilient than expected in the face of higher interest rates. As such, the tightening cycle in the late 2000s could provide an example. Monetary policy stayed for almost three years into restrictive territory before the downturn. But the downturn was due to external factors, i.e. the financial crisis, rather than domestic factors.

Independent Opinion

The views and opinions expressed in this publication are solely and independently those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of any organization or person in any way affiliated with the author including, without limitation, any current or past employers of the author. While reasonable effort was taken to ensure the information and analysis in this publication is accurate, it has been prepared solely for general informational purposes. There are no warranties or representations being provided with respect to the accuracy and completeness of the content in this publication. Nothing in this publication should be construed as providing professional advice on the matters discussed. The author does not assume any liability arising from any form of reliance on this publication.